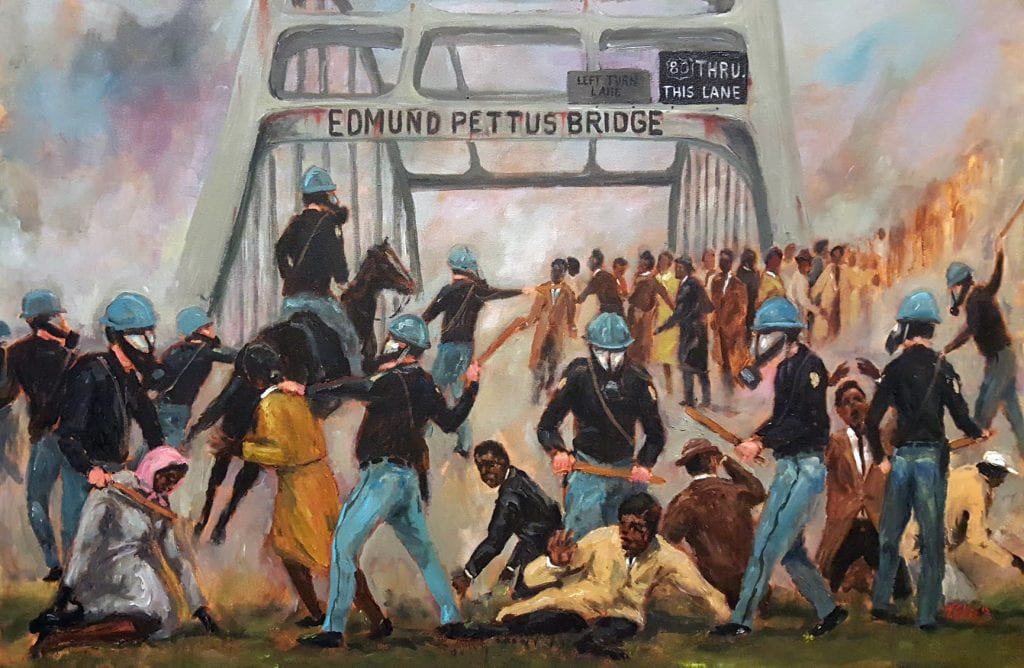

Bloody Sunday by Ted Ellis, Wikimedia Commons

March 7, 2022

March 7 is a sacred day in historical memory. On March 7, 1965, hundreds of Black demonstrators attempted to peacefully walk across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama in a nonviolent march to secure voting rights for millions of disenfranchised Black citizens in Alabama and throughout the South. When they reached a mid-point on the bridge, they were brutally attacked by Alabama state troopers. The vicious beating of peaceful civil rights activists on “Bloody Sunday” revealed the ugly heart of Jim Crow racism to the entire nation, and the world.

Yesterday thousands marched again over the bridge, led by Vice President Kamala Harris.

Today we reflect on the meaning of March 7 in our history and our lives.

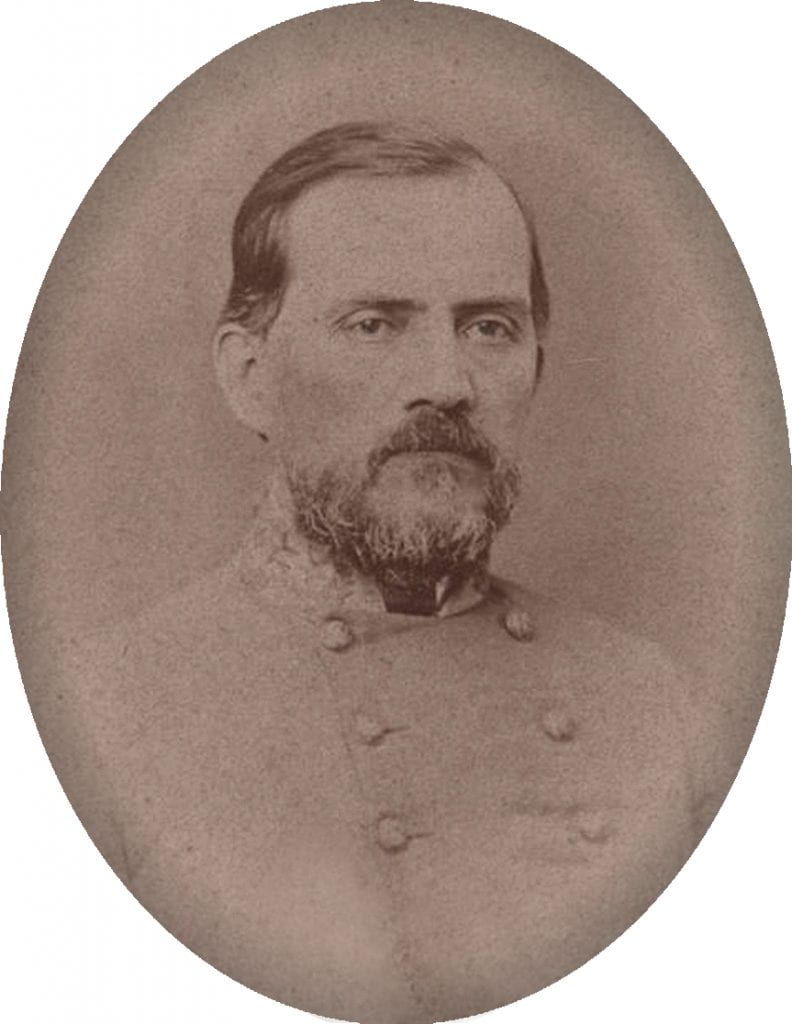

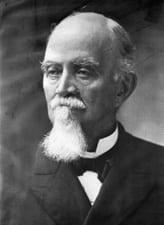

A bridge to honor Edmund Pettus

Photographs from Wikipedia

Edmund Pettus was a Confederate General. When the Alabama KKK formed after the Civil War, he became an active member. During the last year of Reconstruction, he rose to the position of Grand Dragon of the Alabama Klan. During Pettus’s leadership and allegiance to the KKK, the Klan terrorized Alabama’s Black citizens. More Black people were lynched in Alabama then in any other state.

The votes of Black citizens were extinguished in Alabama by the 1875 state constitution, in violation of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. In 1896, Pettus ran for U.S. Senate on a platform of racist hatred, KKK allegiance, and opposition to the post-Civil War amendments. He was elected to the Senate by a vote of the all-white state legislature.

Following his death in July 1907, Alabama Congressman Jams Thomas Heflin gave the eulogy, praising Pettus as “foremost among the defenders of Anglo-Saxon civilization.”

More than thirty years later, in May 1940 – seventy five years after the surrender of the Confederacy at Appomattox — the white leadership of Selma Alabama named a new bridge over the Alabama, an important crossing point for the cotton trade during slavery, to honor him.

Efforts have been made to rename the bridge. But John Lewis opposed doing so. “Renaming the Bridge will never erase its history,” he wrote.

Instead of hiding our history behind a new name we must embrace it —the good and the bad. The historical context of the Edmund Pettus Bridge makes the events of 1965 even more profound. The irony is that a bridge named after a man who inflamed racial hatred is now known worldwide as a symbol of equality and justice. It is biblical—what was meant for evil, God uses for good.

The landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965 was born from the injustices suffered on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and the Bridge itself represents the portal to which America marched towards a brighter, more unified future.

“All that history met on this bridge”

50th Anniversary of the Selma Marches – President Obama speech; Photograph, Pete Souza | Credit: The White House; Wikimedia Commons

Barack Obama is a gifted speaker, as everybody knows. To be honest, though, only two of his speeches are burned into my memory, both delivered in the deep South, within two months of each other: President Obama’s address commemorating the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, delivered in Selma Alabama, on March 7, 2015; and President Obama’s eulogy for Rev. Clementa Pinckney, at pulpit of the Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

Sacred places. Hallowed ground.

In those two speeches, surrounded by African Americans, honoring those beaten and killed by racist violence, Obama found his most authentic, unforgettable voice.

Here is the opening section of his Selma speech, delivered on the Edmund Pettis Bridge.

It is a rare honor in this life to follow one of your heroes. And John Lewis is one of my heroes.

Now, I have to imagine that when a younger John Lewis woke up that morning 50 years ago and made his way to Brown Chapel, heroics were not on his mind. A day like this was not on his mind. Young folks with bedrolls and backpacks were milling about. Veterans of the movement trained newcomers in the tactics of non-violence; the right way to protect yourself when attacked. A doctor described what tear gas does to the body, while marchers scribbled down instructions for contacting their loved ones. The air was thick with doubt, anticipation and fear. And they comforted themselves with the final verse of the final hymn they sung:

“No matter what may be the test, God will take care of you;

Lean, weary one, upon His breast, God will take care of you.”

And then, his knapsack stocked with an apple, a toothbrush, and a book on government — all you need for a night behind bars — John Lewis led them out of the church on a mission to change America.

As John noted, there are places and moments in America where this nation’s destiny has been decided. Many are sites of war — Concord and Lexington, Appomattox, Gettysburg. Others are sites that symbolize the daring of America’s character — Independence Hall and Seneca Falls, Kitty Hawk and Cape Canaveral. Selma is such a place. In one afternoon 50 years ago, so much of our turbulent history — the stain of slavery and anguish of civil war; the yoke of segregation and tyranny of Jim Crow; the death of four little girls in Birmingham; and the dream of a Baptist preacher — all that history met on this bridge.

It was not a clash of armies, but a clash of wills; a contest to determine the true meaning of America. And because of men and women like John Lewis, Joseph Lowery, Hosea Williams, Amelia Boynton, Diane Nash, Ralph Abernathy, C.T. Vivian, Andrew Young, Fred Shuttlesworth, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and so many others, the idea of a just America and a fair America, an inclusive America, and a generous America — that idea ultimately triumphed.

As is true across the landscape of American history, we cannot examine this moment in isolation. The march on Selma was part of a broader campaign that spanned generations; the leaders that day part of a long line of heroes.

We gather here to celebrate them. We gather here to honor the courage of ordinary Americans willing to endure billy clubs and the chastening rod; tear gas and the trampling hoof; men and women who despite the gush of blood and splintered bone would stay true to their North Star and keep marching towards justice.

In both cases, the attack on Bloody Sunday in Selma in 1965, and the murder of parishioners at the Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston SC fifty years later, a similar pattern played out: White supremacist violence directed at Black Americans gathered in prayer.

President Barack Obama at the funeral of Rev. Pinckney, Charleston, S.C., June 26, 2015. (White House Photo by Lawrence Jackson)

Selma, Alabama on March 7, 1965

John Lewis and colleagues at the Edmund Pettis Bridge, Bloody Sunday, just before the attacks, March 7, 1965, photo by Spider Martin, Creative Commons

On March 7, 1965, between 3pm and 4pm, they gathered at the Brown Chapel AME Church, six blocks from the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The Brown Chapel had become the spiritual and strategic headquarters of the Selma campaign to secure voting rights for Black Americans who had been disenfranchised for nearly a century since the end of Reconstruction. John Lewis, Hosea Williams, James Bevel led the mass meeting.

The following account comes from Walking With the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement, by John Lewis (1998).

I read a short statement aloud for the benefit of the press, explaining why we were marching today. Then we all knelt to one knee and bowed our heads as Andy delivered a prayer.

And then we set out, nearly six hundred of us, including a white SCLC staffer names Al Lingo – the same name as the commander of Alabama’s state troopers.

We walked two abreast, in a pair of lines that stretched for several blocks. Hosea and I led the way. Albert Turner, an SCLC leader in Perry County and Bob Mants were right behind us… Mane Foser and Amelia Boyton were next in line, and behind them, stretching as far as I could see, walked an army of teenagers, teachers, undertakers, beauticians – many of the same Selma people who had stood for weeks, months, years, in front of that courthouse.

At the far end, bringing up the rear, rolled four slow-moving ambulances.

I can’t count the number of marches I have participated in in my lifetime, but there was something peculiar about this one. It was more than disciplined. It was somber and subdued, almost like a funeral procession…

When we reached the crest of the bridge, I stopped dead still.

So did Hosea.

There, facing us at the bottom of the other side, stood a sea of blue-helmeted, blue-uniformed Alabama state troopers, line after line of them, dozens of battle-ready lawmen stretched from one side of U.S. Highway 80 to the other.

Behind them were several dozen more armed men – Sheriff Clark’s posse – some on horseback, all wearing khaki clothing, many carrying clubs the size of baseball bats.

On one side of the road I could see a crowd of about a hundred whites, laughing and hollering, waving Confederate flags. Beyond them, at a safe distance, stood a small, silent group of black people….

At the bottom of the bridge, while we were still about fifty feet from the troopers, the officer in charge, a Major John Cloud, stepped forward, holding a small bullhorn up to his mouth.

Hosea and I stopped, which brought the others to a standstill.

“This is an unlawful assembly,” Cloud pronounced. “Your march is not conducive to the public safety. You are ordered to disperse and go back to your church or to your homes.”

“May we have a word with the major?” asked Hosea.

“There is no word to be had,” answered Cloud.

Hosea asked the same question again, and got the same response.

The Cloud issued a warning. “You have two minutes to turn around and go back to your church.”

I wasn’t about to turn around. We were there. We were not going to run. We couldn’t turn and go back even if we wanted to. There were too many people.

We could have gone forward, marching into the teeth of those troopers. But that would have been too aggressive, I thought, too provocative. God knew what might have happened if we had done that. These people were ready to be arrested, but I didn’t want anyone to get hurt.

We couldn’t go forward. We couldn’t go back. There was only one option left that I could see.

“We should kneel and pray,” I said to Hosea.

He nodded.

We turned and passed the word back to begin bowing down in a prayerful manner.

But that word didn’t get far. It didn’t have time. One minute after he had issued his warning – I know this because I was careful to check my watch – Major Cloud issued an order to his troopers.

“Troopers,” he barked. “Advance!”

And then all hell broke loose.

The troopers and possemen swept forward as one, like a human wave, a blur of blue shirts and billy clubs and bullwhips. We had no chance to turn and retreat. There were six hundred people behind us, bridge railings to either side and the river below.

I remember how vivid the sounds were as the troopers rushed toward us – the clunk of the troopers’ heavy boots, the whoops of rebel yells from the white onlookers, the clip-clop of horses’ hooves hitting the hard asphalt of the highway, the voice of a woman shouting, “Get ‘em! Get the niggers!”

And then they were upon us. The first of the troopers came over me, a large husky man. Without a word, he swung his club against the left side of my head. I didn’t feel any pain, just the thud of the blow, and my legs giving way. I raised an arm – a reflex motion – as I curled up in the “prayer for protection” position. And then the same trooper hit me again. And everything started to spin.

I heard something that sounded like gunshots. And then a cloud of smoke rose all around us.

Tear gas.

I’d never experienced tear gas before. This, I would learn later, was a particularly toxic form called C-r, made to induce nausea.

I began choking, coughing. I couldn’t get air into my lungs. I felt as if I was taking my last breath…. I thought, This is it. People are going to die here. I’m going to die here…

I was bleeding badly. My head was now exploding with pain…

There was mayhem all around me. I could see a young kid – a teenaged boy – sitting on the ground with a gaping cut in his head, but blood just gushing out. Several women, including Mrs. Boyton, were lying on the pavement and the grass median. People were weeping. Some were vomiting from the tear gas. Men on horses were moving in all directions, purposely riding over the top of fallen people, bringing their animals’ hooves =down on shoulders, stomachs and legs.

The mob of white onlookers had joined in now, jumping cameramen and reporters….

With nightsticks and whips – one posseman had a rubber hose wrapped with barbed wire – Sheriff Clark’s “deputies” chased us all the way back into the Carver project and up to the front of Brown’s Chapel…

Even then, the possemen and troopers, 150 of them, including Clark. Himself, kept attacking, beating anyone who remained on the street…

Selma Today

Yesterday the eyes of the nation were on Selma. Vice President Kamala Harris gave a rousing speech. Thousands of people came to Selma from all over the country to join her in a march across the bridge: Congresspersons, state and local politicians, leaders of national civil rights organizations, activists, journalists, philanthropists, photographers, citizens who care.

Today they are gone.

Every year they come, as they should. It is good and right that they do. And they spend money in Selma while they are in town, for a day or two, which is also good. Then they leave.

Our nation needs “Selma” as a symbol of racial justice and the march to freedom.

But we seem to have no interest in Selma itself, the living conditions of its denizens, and the socio-economic reality that Selma represents.

Selma Alabama today is a dilapidated American city, hollowed out by poverty, unemployment and neglect, its neighborhoods filled with substandard housing, its business district filled with boarded up buildings, its local economy barely functioning, with a working class population that is over 80% Black.

The online journal Governing “provides analysis and insights for the professionals leading America’s states and localities.” An article published last year focusses on the plight of Selma Alabama: “How a Symbol of Black Equality Became a Center of Black Poverty”.

Selma was once a wealthy city, thanks to agriculture, manufacturing, retail and slavery, but those days are long over. Its downtown buildings are handsome, but many are boarded up or overgrown with ivy. Some of the sidewalks have given way to gravel. What was once a used-car lot across from the St. James is now just weeds.

“It was shocking to see that Selma has not been cared for,” says Kimberly Smith, a Washington, D.C., resident who visited this spring. “Trying to find a restroom, trying to find a place to eat — we thought, ‘My god, there isn’t anything in this town that is in service.’”

Alabama is the sixth poorest states in the United States. Selma is the poorest city in Alabama, and the ninth poorest city in the United States.

Here are the data:

Median household income in California, where I live = $75,235

Median household income in the United States = $67,521

Median household income in Alabama = $46,472

Median household income in Selma = $24,223

Poverty rate for the U.S. – 13.4%

Poverty rate for Alabama = between 16.7% and 18%.

Poverty rate in Selma = 38.3%

Black poverty rate in Selma = 43.8%

According to U.S. News and World Report:

“Selma is the only town in Alabama where over half of all households earn less than $25,000 a year. In Jackson, the second poorest town in the state, the typical household earns just over $30,000. Because so many in Selma live on such low incomes, a relatively large share of the population depends on government support to pay for basic necessities. The SNAP, or food stamps, recipiency rate in Selma is 38%, more than double the 15% rate across the state as a whole.”

As measured by gun homicides and crimes of violence, Selma may be Alabama’s most dangerous city, and one of the 30 most dangerous cities in the United States.

President Obama described Selma 1965 as one of “the places and moments in America where this nation’s destiny has been decided.”

What about Selma in 2022? What about the working poor throughout the “Black Belt” region of the South, where Black Americans were enslaved for centuries before the end of the Civil War, burdened by indentured servitude and Jim Crow terror for nearly a century after, many of whom remain destitute?

How shall we honor this day of sacred memory?

What does it mean to remember Selma?

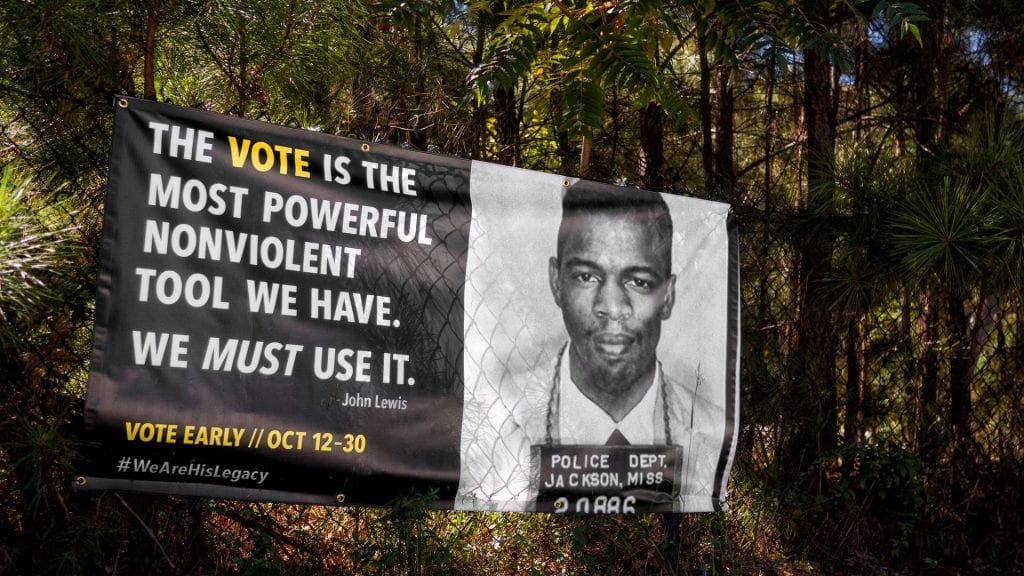

Remembering Selma requires us to honor and carry on the struggle to secure democracy in this country by protecting the right to vote for all citizens.

We honor this day everywhere by remembering all of the men and women, known and unknown, who gave their lives for the right to vote in this nation. We remember James Earl Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, murdered by Klansmen outside Philadelphia, Mississippi on June 21, 1964. We remember Jimmie Lee Jackson, beaten and shot by state troopers in Marion Alabama, just outside Selma, on February 26, 1965, just a week before Bloody Sunday. We remember Reverend James Reeb, beaten to death after marching in Selma, Alabama on March 11, 1965. and we remember Viola Liuzzo, who supported the march from Selma to Montgomery, shot and killed by a Klansman in a passing car on March 25, and many others who died in the Black Freedom Struggle to realize democracy in our country.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. implored us to regard these citizens as are “our sacred martyrs” to whom we owe an enormous debt. There is only one say to repay that debt: by our vigilance to protect and extend voting rights for all American citizens, especially Black and Brown citizens who have been disenfranchised over and over again, generation after generation, by agents of white supremacy, using new tools, tactics and methods.

As President Obama said in 2015, “all of this history met on that bridge…”. We must remember that history and teach it to our students, to our children and to each other.

We honor our sacred martyrs, and everyone who marched from Selma to Montgomery in March 1965, by fighting nonviolently in March 2020, and every day going forward, against racist “white backlash” that has become a virulent poison in our country today, dominating the state legislatures of the former Confederacy and the so-called “red states,” eroding our democracy, and eviscerating the achievements secured by Voting Rights Act of 1965.

We honor the memory and legacy of John Lewis by doing everything possible to ensure that the U.S. Congress enacts the legislation carrying his name — The Freedom to Vote: John R. Lewis Act — which would strengthen legal protections against discriminatory voting policies and practices (which are dramatically increasing in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 6-3 decision in Brnovich v. DNC last year; restore the preclearance requirement of the 1965 Voting Rights Act (which had been erased in 2013 by the Supreme Court’s 5-4 decision Shelby County, Alabama v. Holder); and ensure that elections operate according to national standards, including permitting early voting nationwide, and making Election Day a national holiday. As summarized by the Brennan Center for Justice, the voting rights law honoring John Lewis would modernize and revitalize the Voting Rights Act of 1965… moving us closer to ending discrimination in voting and guaranteeing equal access to the ballot.”

This is how we honor this anniversary: by continuing the freedom struggle for which hundreds met violence on the Edmund Pettus Bridge and for which our sacred martyrs died, the struggle to realize democracy in the United States.

Remembering Selma — the reality of Selma, and what that reality represents — requires even more from us. It requires us to squarely address and take action to rectify the gross inequality of wealth in America, the legacy of slavery and indentured servitude in the former Confederacy, and the scourge of poverty, unemployment, police brutality, and gun violence that continues to plague our nation, most acutely and painfully in Black communities throughout the South, and the North, East and West.

This is from Dr. King’s remarks to the Shop Stewards of Local 815, Teamsters, and the Allied Trades Council, in New York City, on May 2, 1967:

“Negroes have raised the question of poverty as a responsibility of government and placed a new challenge before society — that no government is moral or ethical or blameless if it cannot eliminate poverty today with the abundance of resources and techniques we possess.

Today Negroes want above all else to abolish poverty in their lives, and in the lives of the white poor. This is the heart of their program. To end humiliation was a start, but to end poverty is a bigger task. It is natural for Negroes to turn to the labor movement because it was the first and pioneer anti-poverty program.

It will not be easy to accomplish this program because white America has had cheap victories up to this point. The limited reforms we won have been obtained at bargain rates for the power structure. There are no expenses involved, no taxes are required for Negroes to share lunch counters, libraries, parks, hotels and other facilities. Even the more substantial reforms, such as voting rights, required neither large monetary or psychological sacrifice.

The real cost lies ahead. To enable the Negro to catch up, to repair the damage of centuries of denial and oppression, means appropriations to create jobs and job training; it means the outlay of billions of for decent housing and equal education…

The curse of poverty has no justification in our age. It is socially as cruel and blind as the practice of cannibalism at the dawn of civilization, where men ate each other because they had not yet learned to take food from the soil or to consume the abundant animal life around them. The time has come for us to civilize ourselves by the total, direct, and immediate abolition of poverty.”

We have a grave responsibility today, and every day that follows.

If we fail, our democracy will fail.

We cannot and must not fail.

Jonathan D. Greenberg

John Lewis, Edward M.Kennedy Institute, photograph by Eric Haynes, Creative Commons.