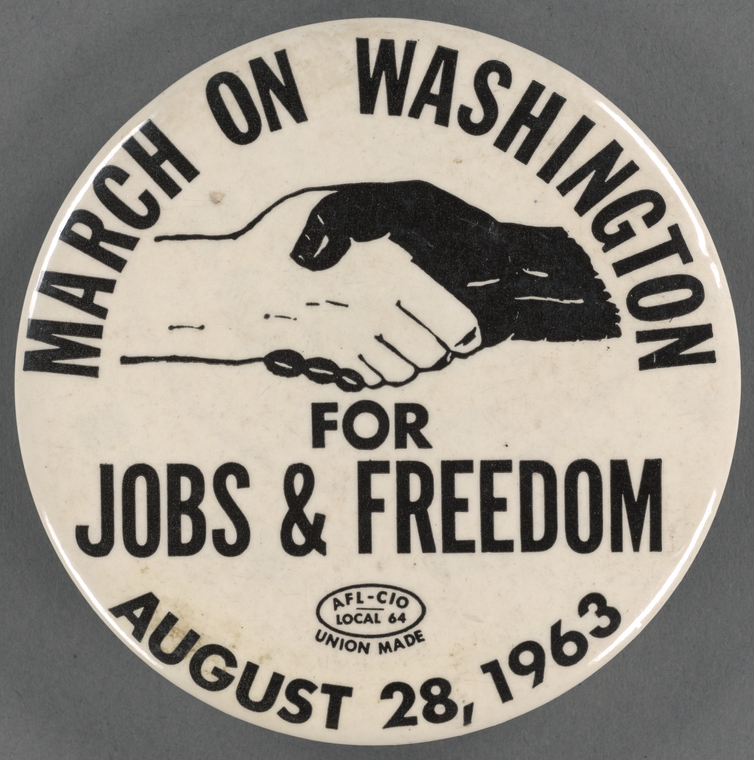

March on Washington August 28 1963 © Jim Wallace, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

March on Washington August 28 1963 © Jim Wallace, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

I have been meditating on the impact and legacy of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom over six decades. I am honored to participate in an interdisciplinary symposium convened by Stanford’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute (“1963 Then & Now: A 60 Year Retrospective of America“) to be held at the Stanford Humanities Center on October 12 and 13, 2023. The following essay sets out reflections I plan to share with colleagues and friends at the symposium.

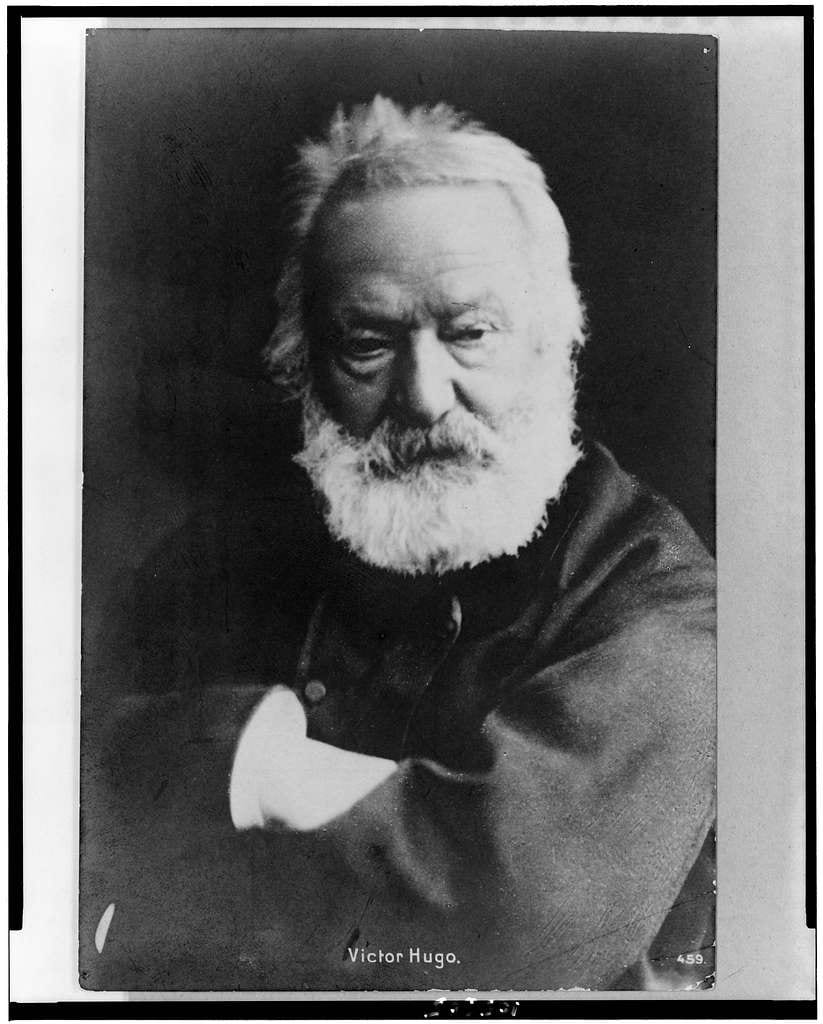

Dr. Clarence B. Jones frequently paraphrases Victor Hugo: “More powerful than the march of mighty armies is an idea whose time has come.”

Perhaps Dr. Jones’s favorite and most cited quotation is from Frederick Douglass, from a speech Douglass gave on August 3, 1857, in Canandaigua, New York, in the period of grave national crisis leading up to the outbreak of Civil War:

“Let me give you a word of the philosophy of reform. The whole history of the progress of human liberty shows that all concessions yet made to her august claims have been born of earnest struggle…

If there is no struggle there is no progress.

Those who profess to favor freedom and yet deprecate agitation are men who want crops without plowing up the ground; they want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.

This struggle may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, and it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle.

Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.“

The 1963 March on Washington, in which Dr. Jones played a major role, brought to the national stage an idea whose time has come — and brought to Congress and the American people a set of urgent demands to rectify racial injustice and achieve job security and economic opportunity for all Americans.

In a tribute to the transformative power of the Black Freedom Movement in the years leading to the March, and the responsiveness of the Johnson Administration and the 89th Congress to what Martin Luther King, Jr. described at the Lincoln Memorial as “the marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community,” important progress was made toward the achievement of these demands in the years immediately following the March.

Tragically, however, these gains have been significantly eroded in recent decades.

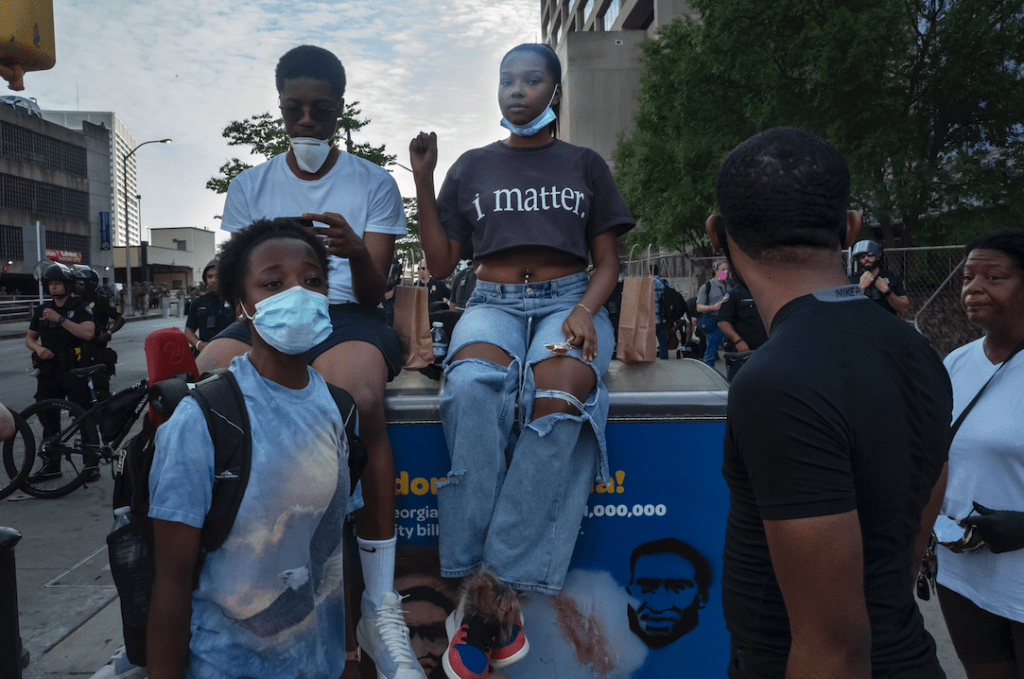

As a result, the demands of the March remain not only an object of historical study but calls to action once again today.

The first part of this essay reiterates the core ideas of the March: the achievement of an intergenerational, interracial and intergenerational nonviolent social revolution to realize the promise of our democracy.

The second part of the essay reviews the specific legislative and policy demands of the March organizers, demands that are too often ignored or overlooked in the feel-good adulation of the closing paragraphs of Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. It acknowledges extraordinary progress that has been made in the intervening years, most especially the overthrow of the Jim Crow apartheid system in the South, and the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, transformative achievements in American history akin to a Second Reconstruction that would not have been secured without the nonviolent mass direct action of the Black Freedom Movement.

The concluding portion of this essay highlights the tragic failure of our government and society to achieve the March’s core demands for equality, justice and freedom. The essay identifies the erosion of many achievements of the civil rights era in the virulent “white backlash” of recent decades — including the re-segregation of American public school education, the evisceration of the Voting Rights Act, and the proliferation of anti-democratic laws weakening or curtailing voting rights in states throughout the nation — and it calls for a renewal of nonviolent mass direct action to secure their achievement.

“An idea whose time has come”

A. Philip Randolph leading the March on Washington, August 28, 1963, National Archives, public domain.

The March on Washington conveyed an idea whose time had come, and conveyed that idea to the entire nation through the mass demonstration of militant nonviolent direct action. The essence of the idea was conveyed by March director A. Philip Randolph in the Opening Remarks of the Lincoln Memorial Program:

“We want a free, democratic society dedicated to the political, economic and social advancement of man along moral lines.

“Now we know that real freedom will require many changes in the nation’s political and social philosophies and institutions. For one thing we must destroy the notion that Mrs. Murphy’s property rights include the right to humiliate me because of the color of my skin. The sanctity of private property takes second place to the sanctity of the human personality.

“It falls to the Negro to reassert this proper priority of values, because our ancestors were transformed from human personalities into private property. It falls to us to demand new forms of social planning, to create full employment, and to put automation at the service of human needs, not at the service of profits-for we are the worst victims of unemployment. Negroes are in the forefront of today’s movement for social and racial justice, because we know we cannot expect the realization of our aspirations through the same old anti-democratic social institutions and philosophies that have all along frustrated our aspirations.

“And so we have taken our struggle into the streets as the labor movement took its struggle into the streets, as Jesus Christ led the multitude through the streets of Judaea. The plain and simple fact is that until we went into the streets the federal government was indifferent to our demands. It was not until the streets and jails of Birmingham were filled that Congress began to think about civil rights legislation. It was not until thousands demonstrated in the South that lunch counters and other public accommodations were integrated. It was not until the Freedom Riders were brutalized in Alabama that the 1946 Supreme Court decision banning discrimination in interstate travel was enforced and it was not until construction sites were picketed in the North that Negro workers were hired.

Those who deplore our militants, who exhort patience in the name of a false peace, are in fact supporting segregation and exploitation. They would have social peace at the expense of social and racial justice. They are more concerned with easing racial tension than enforcing racial democracy.

The months and years ahead will bring new evidence of masses in motion for freedom. The March on Washington is not the climax of our struggle, but a new beginning not only for the Negro but for all Americans who thirst for freedom and a better life….”

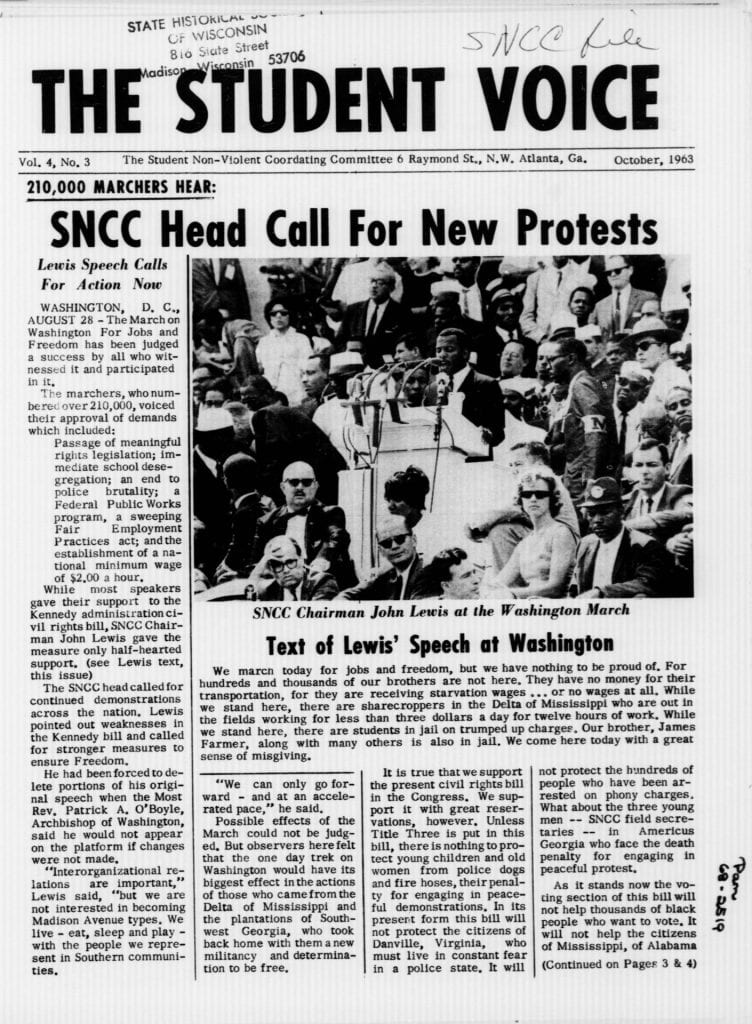

The Student Voice (SNCC), Wisconsin Historical Society digital collection

And the young John Lewis shouted out this powerful idea: “We must get in this revolution and complete the revolution.”

“To those who have said, “Be patient and wait,” we have long said that we cannot be patient. We do not want our freedom gradually, but we want to be free now! We are tired. We are tired of being beaten by policemen. We are tired of seeing our people locked up in jail over and over again. And then you holler, “Be patient.” How long can we be patient? We want our freedom and we want it now. We do not want to go to jail. But we will go to jail if this is the price we must pay for love, brotherhood, and true peace.

I appeal to all of you to get into this great revolution that is sweeping this nation. Get in and stay in the streets of every city, every village and hamlet of this nation until true freedom comes, until the revolution of 1776 is complete.

We must get in this revolution and complete the revolution. For in the Delta in Mississippi, in southwest Georgia, in the Black Belt of Alabama, in Harlem, in Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, and all over this nation, the black masses are on the march for jobs and freedom…

If we do not get meaningful legislation out of this Congress, the time will come when we will not confine our marching to Washington. We will march through the South; through the streets of Jackson, through the streets of Danville, through the streets of Cambridge, through the streets of Birmingham. But we will march with the spirit of love and with the spirit of dignity that we have shown here today.

By the force of our demands, our determination, and our numbers, we shall splinter the segregated South into a thousand pieces and put them together in the image of God and democracy.

We must say: “Wake up America! Wake up!” For we cannot stop, and we will not and cannot be patient…”

Overcoming silence

Rabbi Joachim Prinz and Bayard Rustin at the March on Washington, August 28, 1963, courtesy Lucie Prinz.

The March on Washington was designed as an interfaith gathering of clergy and citizens. Throughout the planning of the March, Jewish rabbis and organizations worked closely with Christian pastors and Church leaders including Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Council, and the National Counsel of Churches.

Dr. Clarence B. Jones believes that the success of the Black Freedom Movement in overthrowing Jim Crow segregation was built upon the alliance of Black and Jewish Americans, and he remembers that a large portion of the white participants at the March were Jewish. When Dr. Jones asked white people about why they came to support the civil rights movement, many told him that they were Jewish, and that their sensitivity to the struggles of Black Americans amidst the violence of Jim Crow evoked their own community’s experience of anti-semitism and genocide. The liberation of Auschwitz took place only 18 years before, and the shadow of the Nazi extermination camps continued to haunt collective memory for Americans as well as Jews in 1963.

In this context, Dr. Jones was especially moved by one of the speakers on the Lincoln Memorial podium — Rabbi Joachim Prinz, President of the American Jewish Congress. Dr. Jones has shared with me that he will never forget Rabbi Prinz’s words on that day:

“When I was the rabbi of the Jewish community in Berlin under the Hitler regime, I learned many things. The most important thing that I learned under those tragic circumstances was that bigotry and hatred are not the most urgent problem. The most urgent, the most disgraceful, the most shameful and the most tragic problem is silence.

“A great people which had created a great civilization had become a nation of silent onlookers. They remained silent in the face of hate, in the face of brutality and in the face of mass murder.

“America must not become a nation of onlookers. America must not remain silent. Not merely black America , but all of America . It must speak up and act,. from the President down to the humblest of us, and not for the sake of the Negro, not for the sake of the black community but for the sake of the image, the idea and the aspiration of America itself.”

“A living petition — in the flesh”

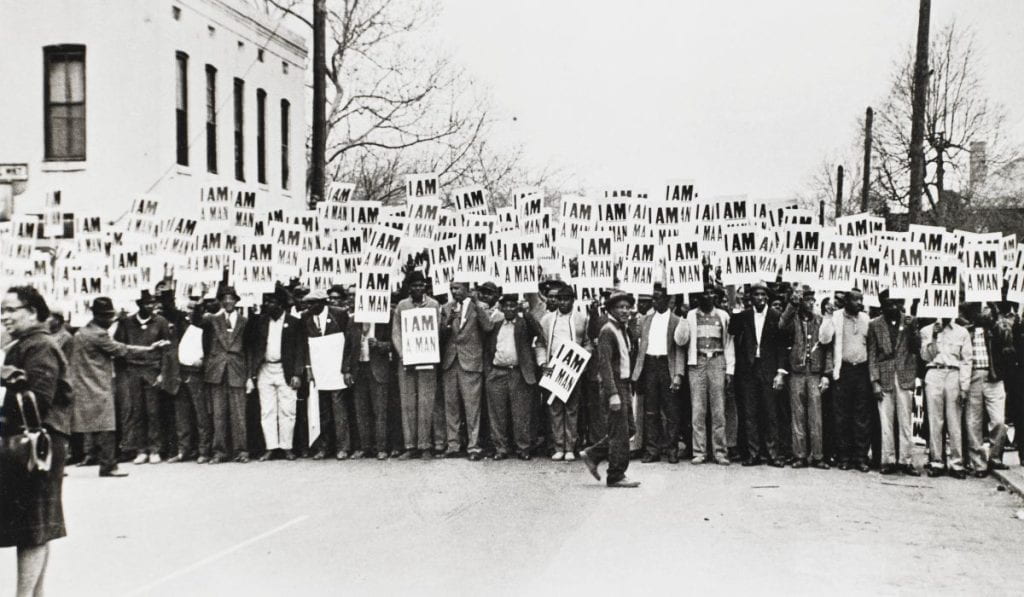

The official statement and demands of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

The official statement and demands of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

As articulated in the official statement of the March on Washington, endorsed by ten sponsoring civil rights and religious organizations, the March was conceived as “a living petition — in the flesh — of the scores of thousands citizens who will be present from all parts of our country.”

The organizers had hoped to reach a goal of 100,000 citizens in attendance. They reached their goal two or three times over.

Everyone remembers that Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. was the last speaker at the March on Washington. But he was not the last speaker. After Dr. King shared his dream, March director A. Philip Randolph came to the podium to introduce Bayard Rustin:

“A philosopher of a non-violent system of behavior in seeking to bring about social change for the advancement of justice, and freedom and human dignity — I want to introduce now Brother Bayard Rustin, who will read the demands of the March on Washington Movement.

Everyone must listen to these demands. That is why we are here.

And now, Bayard Rustin, deputy director of the March will read the demands.”

Then Rustin, who was in fact the top general in the nonviolent military operation we call “the March on Washington” came to the podium and addressed the crowd:

“Friends, at five o’clock today the leaders whom you have heard will go to President Kennedy to carry the demands of this revolution.

“It is now time for you to act.

“I will read each demand and you will respond to it.

“So that when Mr. Wilkins and Dr. King and the other eight leaders go, they are carrying with them the demands which you have given your approval to.

“The first demand is that we have effective Civil Rights legislation, no compromise, no filibuster, and that it include public accommodations, decent housing, integrated education, FEPC, and the right to vote. What do you say? (The crowd erupts in cheers.)

“Number two. They want that we demand the withholding of Federal funds from all programs in which discrimination exists. What do you say? (Loud cheers.)

“We demand that segregation be ended in every school district in the year 1963. (Loud cheers.)

“We demand the enforcement of the 14th Amendment, the reducing of congressional representation of states where citizens are disenfranchised. (Loud cheers.)

“We demand an Executive Order banning discrimination in all housing supported by Federal funds. (Loud cheers.)

“We demand that every person in this nation, black or white, be given training and work with dignity to defeat unemployment and automation. (Loud cheers.)

“We demand that there be an increase in the national minimum wage so that men may live in dignity. (Loud cheers.)

“We finally demand that all of the rights that are given to any citizen be given to black men and men of every minority group including a strong FEPC [Fair Employment Practices Act]. (Loud cheers.)

“WE DEMAND! (Loud cheers.)”

And now ladies and gentlemen, Mr. Randolph will read the pledge. This is a pledge which says our job has just begun. You pledge to return home to carry on the revolution. After Mr. Randolph has read the pledge, I will say, “Do you so pledge?” And you will say, “I do pledge.”

Bayard Rustin speaking at the March on Washington, © Bettmann Archive, NPR,

“Remembering Bayard Rustin: The Man Behind the March on Washington,” 25 Feb. 2021.

Then A. Philip Randolph asked everyone to stand, and he read the pledge, his deep baritone voice echoing from the Lincoln Memorial to the Washington Monument:

“Standing before the Lincoln Memorial on the 28th of August, in the centennial year of emancipation, I affirm my complete personal commitment to the struggle for jobs and freedom for Americans.

“To fulfill that commitment, I pledge that I will not relax until victory is won. I pledge that I will join and support all actions undertaken in good faith in accord with the time-honored Democratic tradition of non-violent protest, of peaceful assembly, and petition, and of redress through the courts and the legislative process.

“I pledge to carry the message of the March to my friends and neighbors, back home and arouse them to an equal commitment and equal effort. I will march and I will write letters. I will demonstrate and I will vote.

“I will work to make sure that my voice and those of my brothers ring clear and determine from every corner of our land.

“I pledge my heart and my mind and my body unequivocally and without regard to personal sacrifice, to the achievement of social peace through social justice.”

This is how the journalist and social critic Murray Kempton described this historic moment, in The New Republic, published the following week (September 4, 1963).

“The moment in that afternoon which most strained belief was near its end, when Rustin led the assemblage in a mass pledge never to cease until they had won their demands. A radical pacifist, every sentence punctuated by his upraised hand, was calling for a $2 an hour minimum wage. Every television camera at the disposal of the networks was upon him. No expression one-tenth so radical has ever been seen or heard by so many Americans.”

Historic gains — followed by backlash, stagnation and loss

What happened to the demands declared by Rustin and Randolph and pledged by tens of thousands at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom?

Lyndon Johnson came to Washington as a Texas Congressman steeped in racist beliefs and language, with strong friendships among the Southern Dixiecrat politicians. From the time he was first elected to the House in 1937 until the mid-1950s, Johnson opposed every civil rights bill that had come before Congress. But Johnson had seen poverty, discrimination and racism first hand, as a teacher in a Mexican American community in Texas, and he understood the power of federal legislation and community investment programs from his role as Texas director of the National Youth Administration as a committed New Deal liberal.

Piven and Cloward argue that, by late 1964, “Lyndon Johnson had little choice but to commit his administration to the cause of civil rights.” Piven and Cloward, Poor Peoples Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail (Vintage, 1978), pp. 245. Piven and Cloward overstate this case. Like Malcolm X, Johnson went through a gradual process of self-transformation on issues related to race in America, a process reflecting the tumultuous changes that the Black Freedom Movement had brought to the South and the nation, as well as his own moral and political development.

But Piven and Coward are right to emphasize the confluence of events that framed Johnson’s decision, and the immense pressures he faced. On September 15, 1964, three weeks after the March on Washington, Southern white racists responded by bombing the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing Denise McNair (age 11), Addie Mae Collins (14), Carole Robertson (14), and Cynthia Wesley (14), and injuring 20 others. President Kennedy, who had promised to enact major civil rights legislation, was assassinated on November 22.

In the years following the March, “Great Society” legislation proposed and advanced of the Lyndon Johnson Administration and the 89th Congress (1965-67) secured extraordinary achievements furthering economic justice and equality of opportunity for all Americans. Johnson put forward 115 pieces of legislation; the 89th Congress enacted 89 of them, achievements that had a transformative impact on American society.

“Never before in the history of the United States has so much been done for civil rights within one presidential administration. A genuine commitment to end inequality appears to have been at the root of legislative initiatives that changed millions of lives, forcing local prejudices to give way to national sensibilities… Lyndon Johnson was able to galvanize congressional and popular forces that, in turn, catalyzed a national will to follow through on centuries of effort to improve the equality of citizens’s status.”

Alexander Tsesis, We Shall Overcome: A History of Civil Rights and the Law (Yale, 2008), p. 250.

What was the impact and legacy of the Great Society legislation on the economic and social conditions of Black Americans? An assessment published in a 1976-77 volume of Political Science Quarterly summarized the gains achieved by Black Americans in the years following enactment of the Johnson Administration’s Great Society legislation:

“The purchasing power of the average black family rose by half. The ratio of black to white income increased noticeably. The Great Society’s efforts were instrumental in generating advancement…

Blacks moved into more prestigious professional, technical, craft, and secretarial jobs previously closed to them. Earnings rose absolutely and relatively as discrimination declined. Sustained tight labor markets, improved education, manpower programs, and equal employment opportunity efforts all played a role.

The improvements in schooling were dramatic and consequential. Black pre schoolers were more likely to enroll than whites, largely because of federally financed early education programs. High school completion increased significantly and compensatory programs provided vital resources to the schools where black youths were concentrated. At the college level, absolute and relative enrollment gains were dramatic, the direct result of government aid programs…”

Sar A. Levitan and Robert Taggart, “The Great Society Did Succeed,” Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 91, No. 4 (Winter, 1976-1977), pp. 601-618 (Published by Oxford University Press).

The impact of the War on Poverty was comparably significant, across all racial and geographic groups.

When President Johnson announced his Great Society program in 1964, he promised substantial reductions in the number of Americans living in poverty. When he left office, he could legitimately argue that he had delivered on his promise. In 1960, 40 million Americans (20 percent of the population) were classified as poor. By 1969, their number had fallen to 24 million (12 percent of the population).

Johnson also pledged to qualify the poor for new and better jobs, to extend health insurance to the poor and elderly to cover hospital and doctor costs, and to provide better housing for low-income families. Here, too, Johnson could say he had delivered. Infant mortality among the poor, which had barely declined between 1950 and 1965, fell by one-third in the decade after 1965 as a result of expanded federal medical and nutritional programs. Before 1965, 20 percent of the poor had never seen a doctor; by 1970, the figure had been cut to 8 percent. The proportion of families living in houses lacking indoor plumbing also declined steeply, from 20 percent in 1960 to 11 percent a decade later.

Steven Mintz, “The Great Society and the Drive for Black Equality,” Digital History, College of Education, University of Houston.

In sum, the achievements of the Johnson Administration’s civil rights, voting rights, and Great Society legislation were unprecedented in American history since Reconstruction, and powerfully impactful. These achievements depended on the unique historical confluence of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, as a significant campaign of the Black Freedom Movement generally, and the responsive partnership of President Johnson and the bipartisan leadership of the 89th Congress.

With the important exception of the dismantling of de jure segregation, however, these hard-fought gains have been significantly undermined or gutted by white backlash and eroded by anti-democratic retrenchment that intensified in the early 1980s and dramatically escalated in the past decade.

Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. lived less than five years following the August 1963 March on Washington. The evolution in Dr. King’s thought over those years provides a framework to understand this process of achievement and retrenchment in race relations and social justice in America.

In his 1964 book Why We Can’t Wait, Dr. King reflects on the March on Washington as an occupation of the nation’s capital by “an army without guns.”

“It was an army into which no one had to be drafted. It was white and Negro, and of all ages. It had adherents of every faith, members of every class, every profession, every political party, united by a single ideal. It was a fighting army, but no one could mistake that its most powerful weapon was love.”

Dr. King reflected on the impact of the March on national public opinion about the African American freedom movement, “how deeply the summer’s activities had penetrated the consciousness of white America,” making every dedicated American “proud that a dynamic experience of democracy in the nation’s capital had been made visible to the world.”

King concludes the book with a chapter reflecting on “The Days to Come” in which he recognizes Lyndon Johnson as a partner in the civil rights struggle. King praises Johnson for his “comprehensive grasp of contemporary problems…. He has seen that poverty and unemployment are grave and growing catastrophes, and he is aware that those caught most fiercely in the grip of this economic holocaust are Negroes. Therefore he has set the twin goal of a battle against discrimination within the war against poverty.”

In 1967, Martin Luther King, Jr. published Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? It was to be the last book he wrote before his assassination on April 4, 1968, and we remain haunted by the urgent question set out in the title, shaken by his warnings about the persistence of virulent racism in American society, and inspired by the deepened and intensified radicalism of his 1967 call to action. He calls for Johnson’s war on poverty to escalate and for the war in Vietnam to end. He intensifies his 1963 call for Black Americans — and poor people of all races — “to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice” by endorsing A. Philip Randolph’s Freedom Budget for All Americans and his own Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged.

Among the prescient analysis of his final book, Dr. King devotes a chapter to “Racism and the White Backlash.”

“It is time for all of us to tell each other the truth about who and what have brought the Negro to the condition of deprivation against which he struggles today…. In short, white America must assume the guilt for the black man’s inferior status.

“Ever since the birth of our nation, white America has had a schizophrenic personality on the question of race. She has been torn between selves — a self iin which she proudly professed the great principles of democracy and a self in which she sadly practiced the antithesis of democracy. This tragic duality has produced a strange indecisiveness and ambivalence toward the Negro, causing America to take a step backward simultaneously with every step forward on the question of racial justice….

“The step backward has a new name today. It is called the “white backlash.” But the white backlash is nothing new. It is the surfacing of old prejudices, hostilities and ambivalences that have always been there… The white backlash of today is rooted in the same problem that has characterized America ever since the black man landed in chains on the shores of this nation. … It lies in the “congenital deformity” of racism that has crippled the nation from its inception… No one surveying the moral landscape of our nation can overlook the hideous and pathetic wreckage of commitment twisted and turned to a thousand shapes under the stress of prejudice and irrationality.”

Looking at each of the March’s specific demands in turn, we see this same pattern: extraordinary legislative and socio-economic achievement followed by anti-democratic retrenchment steeped in racist white backlash.

“Comprehensive and effective civil rights legislation”

Prior to the March on Washington, write Francis Fox Piven and Richard Cloward, [d]espite Kennedy’s announcement that he would press Congress for a greatly strengthened civil rights bill, there was every reason to believe it would be filibustered into oblivion.” Francis Fox Piven and Richard Cloward, Poor Peoples Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail (Vintage, 1978), pp. 245.

Joseph Rauh, Jr., a prominent liberal advocate for labor and social justice, was one of the two leading lobbyists for the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Alongside Clarence Mitchell, who represented the Washington Office of the NAACP, Joe Rauh represented the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, a large group of labor and religious organizations that came together to advocate for the bill’s passage. In an essay reflecting on this experience, Rauh shares his conviction that the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom played a critically important role to move the legislation forward.

“As the [House Judiciary] subcommittee was deliberating, the historic August 28th [1963] March on Washington gave the legislative drive new inspiration. The fears of many that the march would result in incidents on Capitol Hill proved groundless. Instead, [representatives] and senators came to the Lincoln Memorial in buses and, sitting on the steps, heard the crowd chant “pass the bill, pass the bill.” And House Speaker [John W.] McCormack (Dem, MA], after meeting with the leaders of the march, announced that he thought an FEPC could pass the House.”

Joseph L. Rauh, Jr., “The Role of the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights in the Civil Rights Struggle of 1963-64,” in Robert D. Loevy, ed., The Civil Rights Act of 1964: The Passage of the Law that Ended Segregation (State University of New York Press, 1997), p. 49, 58.

Thrust into the presidency, Lyndon Johnson announced his commitment to shepherd through Congress the strongest civil rights legislation since Reconstruction. On November 27, 1963, just five days after Kennedy’s assassination, President Johnson spoke to Congress: “We have talked long enough in this country about equal rights,” he said. “We have talked for one hundred years or more. It is time now to write the next chapter, and to write it in the book of law.”

With fierce determination, and ruthless pressure, Johnson succeeded in enacting the 1964 Civil Rights Bill, and he did more to advance the rights of African Americans than any President since Abraham Lincoln.

Georgia Senator Richard Russell, a close friend and previous political ally of President Johnson’s led a well-organized, fiercely determined filibuster to block passage of any such legislation. On behalf of the Senate’s “Southern Bloc” (18 Senators from the “Dixiecrat” wing of the President’s own Democratic Party, including South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond and North Carolina Senator Robert Byrd, along with Republican Senator John Tower of Texas), Russell promised: “We will resist to the bitter end any measure or any movement which would tend to bring about social equality and intermingling and amalgamation of the races in our [Southern] states.”

Russell, Thurmond, Byrd and their colleagues in the Southern Bloc had reason to believe they would prevail. In 1964, Senate rules required a two-thirds majority to end a filibuster (the procedures known as “cloture”). This threshold had seemed impossible to overcome, as everyone knew that no filibuster on a civil rights bill had ever been broken in U.S. history.

The 1964 filibuster lasted for 60 working days, culminating in a dramatic 14+ hour speech by Senator Byrd, from 7:38pm on Tuesday June 9 until 9:59am on Wednesday, June 10. President Johnson and Senate Whip Hubert Humphrey, who led the effort to enact the bill, mustered the votes for cloture because they recruited a powerful ally in Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen, a Republican from Illinois who considered himself part of the GOP conservative caucus. On June 10, following Byrd’s last stand, spoke to the Senate chamber to endorse the cloture vote.

“Sharp opinions have developed. Incredible allegations have been made. Extreme views have been asserted. For myself, I have but one purpose, and that was the enactment of a good, workable, equitable, practical bill having due regard for the progress made in the civil rights field at the state and local level.

“There are many reasons why cloture should be invoked, and a good civil rights bill enacted. “Victor Hugo wrote in his diary substantially this sentiment: ‘Stronger than all the armies is an idea whose time has come.’ The time has come for equality of opportunity in sharing of government, in education, and in employment. It must not be stayed or denied….

“I appeal to all Senators. We are confronted with a moral issue. Today, let us not be found wanting in whatever it takes by way of moral and spiritual substance to face up to the issue and to vote cloture.”

Dirksen brought an overwhelming majority of Republicans with him to end the filibuster.

In the end, support for the Civil Rights Act was deeply bipartisan. The final vote enacting the bill in the Senate was 73 (46 Democrats + 27 Republicans) to 27 (21 Democrats + 6 Republicans). The bipartisanship, however, did not extend to the South; of the 73 Senators who voted to enact the bill, there was only one Southerner (Sen. Ralph Yarborough of Texas). Still, in the context of today’s rigid and extreme party-line partisanship, and it is astonishing to remember that the percentage of “liberal” Republicans who voted for the Civil Rights bill (82%) was higher than the percentage of “liberal” Democrats who voted for the bill (69%) — a distribution of that is impossible to imagine today, when it would be an anathema for any Congressional Republican to identify as liberal.

On July 2, 1964, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law — ten months after the March, thirteen months after Kennedy went on TV (on June 11, 1963) to make the moral case that Congress ensure that every citizen be granted the right “to enjoy the privileges of being American without regard to his race or his color.” The Act achieved several of the most important demands that had been made at the March, guaranteeing all Americans access to public accommodations (including hotels, restaurants, theaters and other business places where business is conducted) and federally funded programs, prohibiting discrimination in employment, public education, public libraries, parks and swimming pools.

In effect, with the passage of the 1964 Act, the legal system of Jim Crow segregation was torn down. Access to public accommodations was secured, and remains so. The dismantling of de jure segregration is one of the greatest achievements in American history, permanently removing the ubiquitous “Whites Only” signs from restaurants, hotels, and places of business in every former Confederate state. Never again would Black motorists be forced to depend on the ‘Green Book” to enable a safe journey through South, to find a motel to get some sleep, a restaurant at which they could dine at peace, an amusement park open for a family’s children.

Enforcement of 15th Amendment voting rights for all Americans

Martin Luther King, Jr. and President Lyndon Johnson at the White House, 3 December 1963.

LBJ Library photo by Yoichi Okamoto, LBJ Library, public domain.

On February 3, 1870, with the ratification of the 15th Amendment to the US Constitution, the United States became a democratic nation. For the first time, the Constitution affirmed that “”[t]he right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” and empowered Congress to enact legislation to enforce voting rights for all citizens.

In August 1963, a hundred years after the Emancipation Proclamation, 93 years after the 15th Amendment was ratified, Black Americans remained disenfranchised throughout the former Confederate states.

Countless Black citizens were martyred because they tried to exercise their 15th Amendment voting rights in the intervening years.

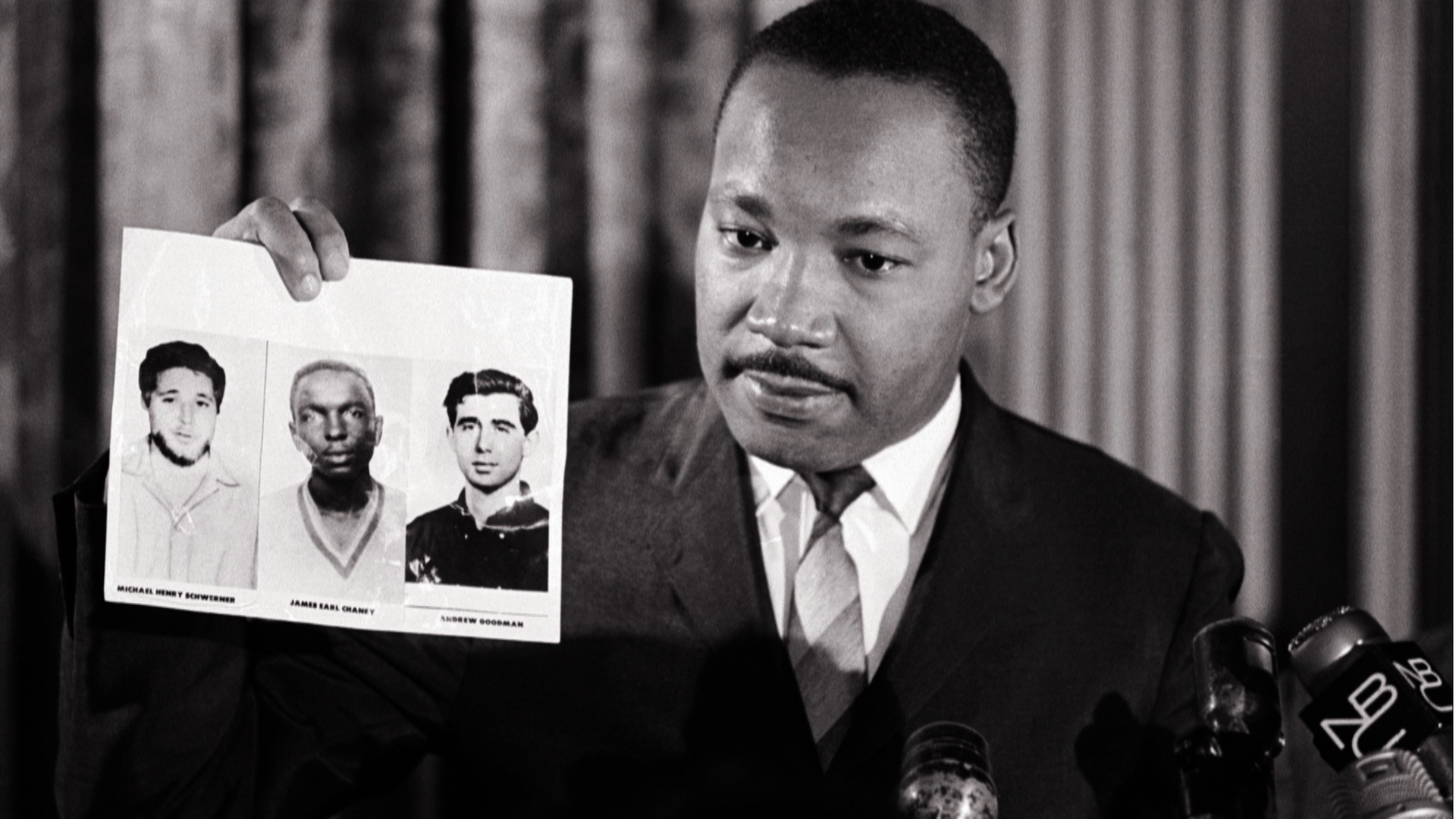

On June 21, 1964 — just two weeks before the Civil Rights Act was passed — Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner were murdered in Mississippi for their efforts to register Black voters during the Freedom Summer voting rights campaign.

Dr. King holds photograph of the three voting rights activists who disappeared, and later found murdered, 1964, PBS, American Experience., US History Collection

In the aftermath of the Civil Rights Act passage, Dr. King and other civil rights leaders met at the White House to urge President Johnson to immediately endorse comprehensive voting rights legislation. Johnson told King that he had used up his political capital on the public accommodations bill, that he didn’t have the power to secure passage of a major voting rights bill so soon.

Leaving the White House, Andrew Young asked Dr. King: “What are we going to do now?” King responded: “We’re going to get him the power.”

The effort to get President Johnson the power focussed on the Selma campaign.

March 7, 1965, Bloody Sunday. On the Edmund Pettis Bridge, John Lewis and many other marchers got their heads bashed by Alabama state troopers, in a demonstration of racist brutality witnessed on television by a shocked nation.

One week later, on March 15, President Johnson addressed a Joint Session of Congress. Speaking “for the dignity of man and the destiny of democracy,” Johnson linked Selma to the sacred sites of America’s struggle for freedom. I include a long excerpt of President Johnson’s address to highlight how closely it follows the rhetorical framework and echoes the core themes of Martin Luther King’s speech before the Lincoln Memorial at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963:

“At times history and fate meet at a single time in a single place to shape a turning point in man’s unending search for freedom. So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama. There, long-suffering men and women peacefully protested the denial of their rights as Americans. Many were brutally assaulted. One good man, a man of God, was killed….

“Our mission is at once the oldest and the most basic of this country: to right wrong, to do justice, to serve man…

“Rarely are we met with a challenge, not to our growth or abundance, or our welfare or our security, but rather to the values, and the purposes, and the meaning of our beloved nation.

“The issue of equal rights for American Negroes is such an issue.

“And should we defeat every enemy, and should we double our wealth and conquer the stars, and still be unequal to this issue, then we will have failed as a people and as a nation. For with a country as with a person, ‘What is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?’

“There is no Negro problem. There is no Southern problem. There is no Northern problem. There is only an American problem. And we are met here tonight as Americans — not as Democrats or Republicans. We are met here as Americans to solve that problem.

“This was the first nation in the history of the world to be founded with a purpose. The great phrases of that purpose still sound in every American heart, North and South: “All men are created equal,” “government by consent of the governed,” “give me liberty or give me death.” Well, those are not just clever words, or those are not just empty theories. In their name Americans have fought and died for two centuries, and tonight around the world they stand there as guardians of our liberty, risking their lives.”

“Those words are a promise to every citizen that he shall share in the dignity of man….

“Our fathers believed that if this noble view of the rights of man was to flourish, it must be rooted in democracy. The most basic right of all was the right to choose your own leaders. The history of this country, in large measure, is the history of the expansion of that right to all of our people. Many of the issues of civil rights are very complex and most difficult. But about this there can and should be no argument.

“Every American citizen must have an equal right to vote.

“There is no reason which can excuse the denial of that right. There is no duty which weighs more heavily on us than the duty we have to ensure that right.

“Yet the harsh fact is that in many places in this country men and women are kept from voting simply because they are Negroes. Every device of which human ingenuity is capable has been used to deny this right…

“For the fact is that the only way to pass these barriers is to show a white skin. Experience has clearly shown that the existing process of law cannot overcome systematic and ingenious discrimination. No law that we now have on the books — and I have helped to put three of them there — can ensure the right to vote when local officials are determined to deny it. In such a case our duty must be clear to all of us. The Constitution says that no person shall be kept from voting because of his race or his color. We have all sworn an oath before God to support and to defend that Constitution. We must now act in obedience to that oath.

President Johnson addresses a joint session of Congress on voting rights, March 15, 1968

“Wednesday, I will send to Congress a law designed to eliminate illegal barriers to the right to vote…

“This bill will strike down restrictions to voting in all elections — Federal, State, and local — which have been used to deny Negroes the right to vote. This bill will establish a simple, uniform standard which cannot be used, however ingenious the effort, to flout our Constitution. It will provide for citizens to be registered by officials of the United States Government, if the State officials refuse to register them…

“To those who seek to avoid action by their National Government in their own communities, who want to and who seek to maintain purely local control over elections, the answer is simple: open your polling places to all your people.

“Allow men and women to register and vote whatever the color of their skin.

“Extend the rights of citizenship to every citizen of this land.

“There is no constitutional issue here. The command of the Constitution is plain. There is no moral issue. It is wrong — deadly wrong — to deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote in this country. There is no issue of States’ rights or national rights. There is only the struggle for human rights. I have not the slightest doubt what will be your answer.

“But the last time a President sent a civil rights bill to the Congress, it contained a provision to protect voting rights in Federal elections. That civil rights bill was passed after eight long months of debate. And when that bill came to my desk from the Congress for my signature, the heart of the voting provision had been eliminated. This time, on this issue, there must be no delay, or no hesitation, or no compromise with our purpose.

“We cannot, we must not, refuse to protect the right of every American to vote in every election that he may desire to participate in. And we ought not, and we cannot, and we must not wait another eight months before we get a bill. We have already waited a hundred years and more, and the time for waiting is gone…

“But even if we pass this bill, the battle will not be over. What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches into every section and State of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life. Their cause must be our cause too. Because it’s not just Negroes, but really it’s all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice.

“And we shall overcome.

“As a man whose roots go deeply into Southern soil, I know how agonizing racial feelings are. I know how difficult it is to reshape the attitudes and the structure of our society. But a century has passed, more than a hundred years since the Negro was freed. And he is not fully free tonight.

“It was more than a hundred years ago that Abraham Lincoln, a great President of another party, signed the Emancipation Proclamation; but emancipation is a proclamation, and not a fact. A century has passed, more than a hundred years, since equality was promised. And yet the Negro is not equal. A century has passed since the day of promise. And the promise is un-kept.”

“The time of justice has now come. I tell you that I believe sincerely that no force can hold it back…”

“There’s really no part of America where the promise of equality has been fully kept. In Buffalo as well as in Birmingham, in Philadelphia as well as Selma, Americans are struggling for the fruits of freedom. This is one nation. What happens in Selma or in Cincinnati is a matter of legitimate concern to every American. But let each of us look within our own hearts and our own communities, and let each of us put our shoulder to the wheel to root out injustice wherever it exists.

“The real hero of this struggle is the American Negro. His actions and protests, his courage to risk safety and even to risk his life, have awakened the conscience of this nation. His demonstrations have been designed to call attention to injustice, designed to provoke change, designed to stir reform. He has called upon us to make good the promise of America. And who among us can say that we would have made the same progress were it not for his persistent bravery, and his faith in American democracy…

“In Selma, as elsewhere, we seek and pray for peace. We seek order. We seek unity. But we will not accept the peace of stifled rights, or the order imposed by fear, or the unity that stifles protest. For peace cannot be purchased at the cost of liberty…

“Of course, people cannot contribute to the nation if they are never taught to read or write, if their bodies are stunted from hunger, if their sickness goes untended, if their life is spent in hopeless poverty just drawing a welfare check. So we want to open the gates to opportunity. But we’re also going to give all our people, black and white, the help that they need to walk through those gates…

“This is the richest and the most powerful country which ever occupied this globe. The might of past empires is little compared to ours. But I do not want to be the President who built empires, or sought grandeur, or extended dominion.

“I want to be the President who educated young children to the wonders of their world.

“I want to be the President who helped to feed the hungry and to prepare them to be tax-payers instead of tax-eaters.

“I want to be the President who helped the poor to find their own way and who protected the right of every citizen to vote in every election.

“I want to be the President who helped to end hatred among his fellow men, and who promoted love among the people of all races and all regions and all parties.

“I want to be the President who helped to end war among the brothers of this earth…”

“Young man walking in the Selma March, Selma, Alabama” 1965, © Bruce Davidson

Johnson signed into law the 1965 Voting Rights Act on August 6, 1965, securing the right to vote or Black people who had been disenfranchised since the end of Reconstruction.

The effect of the Voting Rights Act was swift and far-reaching. As summarized by Alexander Tsesis,

“Disenfranchisement devices like literacy tests were immediately suspended in Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Georgia, South Carolina, Virginia and parts of North Carolina. In other states, the U.S. attorney general was granted the authority to file lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of poll taxes in nonfederal elections… Before its enactment, 24.6 percent of blacks in the Deep South were registered to vote; by 1967 the number was 56.5 percent. The shift in the region was remarkable. Between 1964 and 1970 black voter registration in Mississippi rose from 6.7 percent to 68 percent; in Alabama from 19.3 percent to 51.6 percent; and in. South Carolina from 37.3 percent to 51.2 percent. These gains translated into increased black voting, candidate eligibility, and office holding.”

Alexander Tsesis, We Shall Overcome: A History of Civil Rights and the Law (Yale, 2008), p.249

The most important provisions in the Act, the provisions that gave the Act teeth to stop states from developing new forms of racist-fueled disenfranchisement in the future, were Section 4(b), which set out a formula for identifying jurisdictions with a history of racial discrimination, and Section 5, which required them to obtain a “preclearance” determination from the U.S. Attorney General (or a panel of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia) to confirm that proposed changes to their voting laws going forward would not “deny or abridge the right to vote on account of race, color, or membership in a language minority group.”

Sections 4 and 5 of the 1965 Voting Rights were enforced until 2013, when the Supreme Court’s 5-4 decision in Shelby County v. Holder invalidated Section 4 as unconstitutional, thereby eviscerating Section 5 as a practical matter, given the reality of partisan politics in the U.S Congress.

Here is an excerpt from Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s dissent in Shelby County (with Justice Breyer, Justice Sotomayor, and Justice Kagan joining):

In the Court’s view, the very success of §5 of the Voting Rights Act demands its dormancy. Congress was of another mind. Recognizing that large progress has been made, Congress determined, based on a voluminous record, that the scourge of discrimination was not yet extirpated… With overwhelming support in both Houses, Congress concluded that, for two prime reasons, §5 should continue in force, unabated… “[V]oting discrimination still exists; no one doubts that.” Ante, at 2. But the Court today terminates the remedy that proved to be best suited to block that discrimination.

Within 24 hours of the court’s decision in Shelby, Texas, Mississippi and Alabama began to implement new laws to curtail citizens’ voting rights, laws that had been previously barred because of the Voting Rights Act Section 5 preclearance requirement. (“The Effects of Shelby County v. Holder,” Brennan Center for Justice, August 6 2018).

Over the subsequent months and years, many jurisdictions throughout the United States, including many of those previously identified under Section 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act, have enacted new voter restrictions that have had a disproportionate impact on Black voters. (See e.g. “The Impact of Voter Suppression on Communities of Color,” Brennan Center for Justice, January 10, 2022). As a result, in the words of Ari Berman, we are witnessing “the greatest assault on voting rights since the end of Reconstruction.” See also Carol Anderson, One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Democracy (Bloomsbury, 2018); Gilda Daniels, Uncounted: The Crisis of Voter Suppression in America (NYU Press, 2020), and Jim Downs, ed, Voter Suppression in U.S. Elections (University of Georgia Press, 2020).

After eviscerating Sections 4 and 5 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, the Supreme Court took action to weaken Section 2 of the Act, which prohibits states and localities from imposing any “qualification or prerequisite to voting or standard, practice, or procedure…in a manner which results in a denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color[.]” Following the appointment of three Trump-appointed Justices to the Supreme Court, the court in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee (2021) narrowly interpreted Section 2 to make it more difficult to challenge discriminatory voting laws in court.

The gutting of the 1965 Voting Rights by the Supreme Court in Shelby County and Brnovich and the proliferation of state legislative measures to restrict voting rights for all Americans, most especially for citizens of color, is a grave threat to our democracy.

To address this threat, rectify the harms that have already been imposed, and restore and strengthen the gains achieved in the 1965 Voting Rights Act, those millions of us who seek to carry forward the democratic vision of the March on Washington unite to demand that Congress enact the The John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act and the Freedom to Vote Act — NOW.

“Adequate and integrated education”

African American school children entering the Mary E. Branch School, Farmville, Virginia, 1963; O’Halloran, Thomas, photographer; public domain.

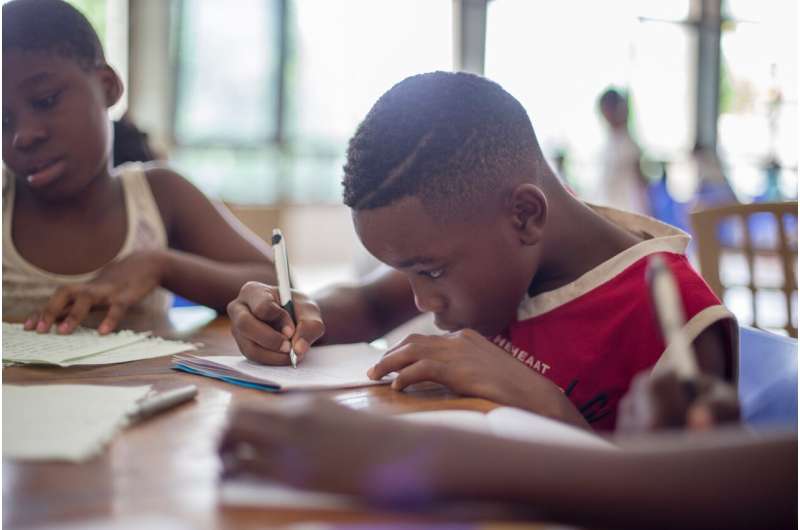

The March organizers and participants called for the end of segregation in every school district in America in 1963.

The centerpiece of efforts of the Johnson Administration and the 89th Congress to achieve this goal was the enactment of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965. For the first time, ESEA empowered the federal government to make significant investments in public primary and secondary education in an effort to bolster equality of opportunity and access to quality education, including a $1.1 billion program of grants to states earmarked for school districts with low-income families.

The ESEA also established Head Start as a permanent program following an initial eight-week demonstration project. “Designed to help break the cycle of poverty,” Head Start “gave preschool children from families with low income a comprehensive program to meet their emotional, social, health, nutritional, and educational needs.” Head Start History, Office of Head Start, US Department of Health and Human Services. The ESEA also established the National Teacher Corps to train and retain teachers for disadvantaged school districts in low-income areas.

Tragically, however, American schools are still segregated and unequal six decades later. Today, children from millions of low income families are denied access to education at a level of financial resources, class size and teacher quality comparable to the opportunities afforded to children living in wealthy districts.

As documented by EdBuild.org: “Despite more than a half-century of integration efforts, the majority of America’s school children still attend racially concentrated school systems. This is reflective of the long history of segregation—policies related to everything from voting to housing—that have drawn lines and divided our communities.” Inequality is starkly demonstrated by the related financial disparities: “Nonwhite school districts throughout the United States receive $23 billion less per year than white districts serving the same number of students.”

Unsplash Creative Commons, public domain

Three months ago, on May 19, 2023, the U.S. Department of Education released a major report“The State of School Diversity in the United States” (the 2023 Report) documenting pervasive racial segregation and socioeconomic inequality in American public education today: “Based on currently available Department data and a review of educational and economic research, the report finds that progress toward increased racial and socio-economic diversity has stalled in many communities as segregation patterns have persisted, leading to inequitable access and outcomes for students.”

The 2023 Report highlights progress toward equity and integration in the wake of the civil rights movement, and the passage of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965 (enacted pursuant President Johnson’s “War on Poverty”).

“Black students had more equitable access to the school resources and opportunities available to their white peers in the time period between the 1960s through the 1980s; including the years directly following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the ESEA. Following the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the ESEA, some states changed their school funding formulas, which led to higher per pupil expenditures, smaller class sizes, and improved high school graduation for Black and Latino students. At the height of school desegregation efforts in the 1980s, among 13-year-olds, the achievement gap for Black students had decreased by more than half in reading and nearly half in math (see Figures 2 and 3), suggesting that these efforts may have been associated with improvements in educational outcomes.”

Among other factors, progress toward greater racial equity has been hampered by the use of local property taxes to fund schools:

“In the most inequitable cases, wealthy neighborhoods can fund schools and high-quality programs, recruit more experienced educators, offer more advanced courses, maintain and provide educationally appropriate and equitable facilities, and better prepare students for college and career success while schools in low-income neighborhoods struggle to educate students with the most need. In states with inequitable funding formulas, schools serving more students of color or more students from low-income backgrounds have fewer dollars to support those students.52 For example, some research has shown that districts serving the highest percentage of Black, Latino, or Native American students receive $1,800 less per student than those with fewer students of color. However, when accounting for the funding required to address the needs of underserved students, this gap in funding grows substantially.”

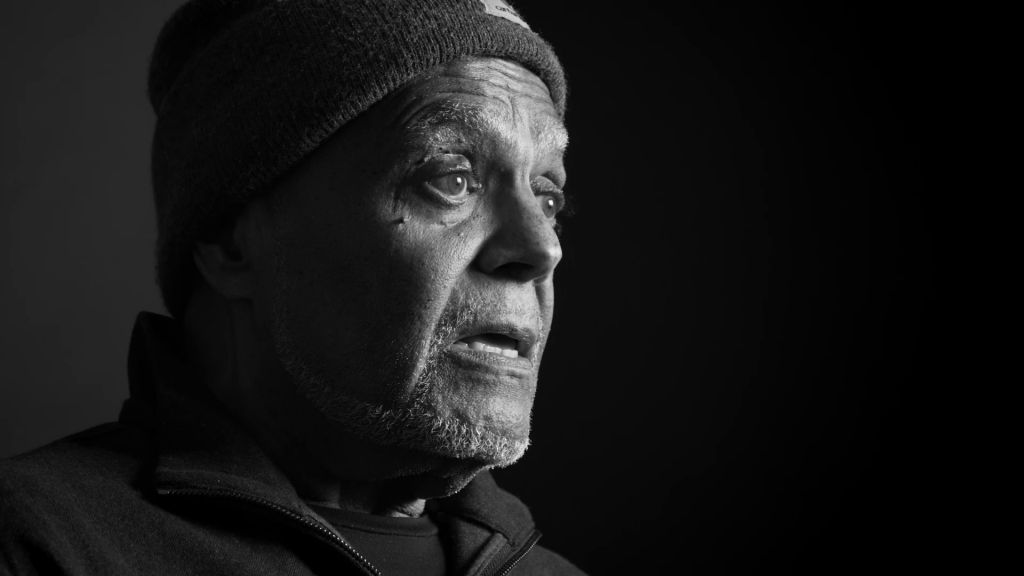

Bob Moses, 2019, Photograph by Paul Ryan

Robert Parris Moses led the Mississippi Voter Registration project for SNCC, organized Freedom Summer, and joined Fannie Lou Hamer to organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. In the early 1980s, Moses founded The Algebra Project, and continued to lead the project until his death on July 25, 2021. “The Algebra Project uses mathematics literacy as an organizing tool to guarantee quality public school education for all children in the United States of America.” In the words of Bob Moses:

“In the 1960s, it wasn’t radical to do voter registration per se. What was radical was to mount an insurgency to ensure that Black sharecroppers in the Mississippi Delta voted. In the morning dawn of the 21st century, it isn’t radical to do algebra per se. What is radical is to mount insurgencies to ensure that students at the bottom get the literacies they need.”

This was our task in 1963, securing quality education for all children in every state. And it remains our task today — a task made even more challenging by severe teacher and staff shortages and a chronic truancy/attendance and literacy crisis in public schools throughout the country, most especially in disadvantaged communities.

Fair treatment, dignified work, and economic security

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Art and Artifacts Division, The New York Public Library, 1963.

The March called for Jobs and Freedom, intertwined necessities for a life of dignity in the wealthiest society in the world. This call affirms the reality that the practice of citizenship, the protection of civil liberties, the achievement of racial justice, and the realization of human rights depend upon economic security.

The inseparable relation of jobs and freedom is highlighted by the history of slavery which had forced Black Americans to work in forced labor, without wages or basic rights, under conditions of extreme injustice, cruel exploitation, relentless humiliation and brutal oppression, for more than two centuries: from August 1619, when the first slaves ship arrived in Virginia, to January 31, 1865, when the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery and forced servitude was ratified and proclaimed.

In August 1963, at the Lincoln Memorial, Dr. King decried the failure of the United States to create racial equality over the intervening century. “Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation,” King told the great assembly. “But one hundred years later the Negro still is not free… One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity.”

King’s deep concern about poverty was longstanding, even has he had grown up in a middle class family and neighborhood. Without experiencing hardship firsthand, he recognized the widespread unemployment and deprivation within the surrounding Black community. “The inseparable twin of racial injustice was economic injustice,” the 21-year-old King wrote in a college paper. “Although I came from a home of economic security and relative comfort, I could never get out of my mind the economic insecurity of many of my playmates and the tragic poverty of those living around me.” King’s moral imagination led him to pursue a ministry framed by the Social Gospel and focussed on the poorest and most vulnerable, “the least of these brothers and sisters of mine” (Matthew 25:40-45).

King’s focus was not charity but structural reform to enable all people to enjoy a life of fair treatment, dignified work, and economic security, a meaningful and dignified job at decent wages.

In the struggle to defend the rights of poor and working people, “[t]he two most dynamic and cohesive liberal forces in the country are the labor movement and the Negro freedom movement,” Dr. King told the audience of the AFL-CIO National Convention on December 11, 1961. “Together we can be architects of democracy.”

Cleveland Robinson, senior officer of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU) and the Negro American Labor Council (NALC) was a key organizer of the 1963 March alongside A. Philip Randolph. King, Randolph, Robinson and other leaders of the 1963 March pushed to move the country toward a greater alignment with the movement for workers rights, as they pushed the labor establishment to overcome its own racist past — and present.

In a major blow to Randolph, Rustin and King, the AFL-CIO voted overwhelmingly not to endorse the March. But the United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America (UAW) endorsed the March — Walter Reuther, the powerful UAW President and Chairman of the AFL-CIO Industrial Union Department, was a prominent member of the March organizing committee, and speaker on the Lincoln Memorial program. A broad away of progressive unions, including the United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA) and the Negro American Labor Council (NALC) attended in force.

Even in the absence of AFL-CIO endorsement, “[t]he march culminated the civil rights-labor alliance,” writes historian Michael Honey, “with thousands of trade unionists brought to the march by unions from industrial and urban centers across the country.” Michael K. Honey, To the Promised Land: Martin Luther King and the Fight for Economic Justice (Norton, 2018).

This history explains why four of the ten core demands of the March were about jobs:

- “A massive federal program to train and place all unemployed workers — Negro and white — on meaningful and dignified jobs at decent wages.

- “A national minimum wage act that will give all Americans a decent standard of living. (Government surveys shjow that anything less than $2.00 an hour fails to do this.)

- “A broadened Fair Labor Standards Act to include all areas of employment which are presently excluded; and

- “A federal Fair Employment Practices Act barring discrimination by federal, state and municipal governments, and by employers, contractors, employment agencies, and trade unions.”

At the heart of each of these demands is the insistence that all workers be treated with dignity. In effect, these demands sought to expand and extend New Deal policies to groups that had been excluded from the original legislative formulations of the FDR era, especially African Americans, and to raise the economic floor — the minimum set of workers wages and rights, fair and equal employment opportunity, and access to necessary training and to a decent job — for every American, regardless of race, especially the unemployed and working poor who had been excluded from the benefits of the postwar economic boom.

President Lyndon Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act beside Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and other civil rights leaders, August 6, 1965.

LBJ Library photo A1030-8a by Yoichi Okamoto

In his State of the Union Address on January 8, 1964, President Johnson announced radically transformative aspirations for the 89th Congress:

“Let this session of Congress be known as the session which did more for civil rights than the last hundred sessions combined… as the session which declared all-out war on human poverty and unemployment in these United States… and as the session which helped to build more homes, more schools, more libraries, and more hospitals than any single session of Congress in the history of our Republic.”

Johnson’s War on Poverty and related programs of the Nixon Administration significantly expanded federal spending on social services, public assistance, public housing, medical coverage and legal services for the poor.

President Johnson dedicated his Presidency to “the Great Society” through massive federal government investment in social and economic policies and programs designed to eliminate poverty, overcome racial injustice, and provide economic opportunity to all Americans, and create a more fair and egalitarian distribution of national wealth.

In addition to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and federal aid to education through the ESEA and the Teacher Corps, Congress enacted legislation to fund and implement an unprecedented group of social democracy programs under the Great Society framework, including the establishment of major health entitlement programs Medicare (providing national health insurance coverage for older Americans) and Medicaid (providing health coverage for low income and disabled Americans of any age), and the establishment and expansion of community health programs; the Immigration and Nationality Services Act of 1965 (abolishing previous national-origin quotas that prioritized Europeans); and a wide variety of legislation pursuant to Johnson’s “War on Poverty,” including:

- The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 allocated large investments to address poverty and authorized the federal government to fund local and community based private and nonprofit organizations directly, rather than funneling money through state or local governments, thereby enabling federal agencies to avoid or work around racist state and local governments that had long supported segregation and eliminated Black citizens from participation in political decision-making. The Act established the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) as an independent federal agency to oversee a variety of community-based antipoverty, education, job training, and community development programs. (The OEO later moved to Health and Human Services as the Office of Community Services). Major programs established by the Act and administered by the OEO included:

-

- The Job Corps (which sixty years later remains the largest federal residential job training program ever established in the United States) and the Neighborhood Youth Corps, which provided 14- to 21-year-old youths from low-income families the opportunity to gain work experience and earn income while completing high school);

-

- Federal Work-Study programs for university students; Upward Bound, which assisted poor high school students entering college; and Adult Basic Education grants.

-

- Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA) and Voluntary Assistance for Needy Children;

-

- Community Action Programs, defined in the Act as: a program (2) “which provides services, assistance, and other activities of sufficient scope and size to give promise of progress toward elimination of poverty or a cause or causes of poverty through developing employment opportunities, improving human performance, motivation, and productivity, or bettering the conditions under which people live, learn, and work; (3) which is developed, conducted, and administered with the maximum feasible participation of residents of the areas and members of the groups served; and (4) which is conducted, administered, or coordinated by a public or private nonprofit agency (other than a political party), or a combination thereof;” and

- The Food Stamp Act of 1964 (which expanded and made permanent the federal food stamp program);

- The Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964, the first major federal support for urban mass transit projects throughout the United States, which established the Urban Mass Transit Administration (now the Federal Transit Administration);

- The Public Works and Economic Development Act of 1965, “to provide grants for public works and development facilities, other financial assistance and the planning and coordination needed to alleviate conditions of substantial and persistent unemployment and underemployment in economically distressed areas and regions;”

- The Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965, establishing a new cabinet-level Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and providing rent subsidies for low-income families, home improvement grants for enable low-income homeowners, and improved relocation benefits; and the launching of the Model Cities Program (funding low-income housing; urban redevelopment, including building of community centers, recreations facilities, hospitals and schools, alongside social service programs including outreach health care services, early child and adult education programs, minority economic development councils, food assistance programs, and centers for disabled community members); and the Demonstration Cities Act of 1966 “to assist comprehensive city demonstration programs for rebuilding slum and blighted areas and for providing the public facilities and services necessary to improve the general welfare of the people who live in those areas, to assist and encourage planned metropolitan development,” including funding for neighborhood renewal, prioritizing strategic investments in housing renovation, urban services, neighborhood facilities, and related job creation activities;

- Major amendments to Social Security in 1965 and 1967 which significantly increased benefits, expanded coverage, including hospital insurance, and established new programs to combat poverty and raise living standards, including an increase in cash benefits, a more liberal eligibility threshold for disability coverage, funding for maternal and child health and family planning, and other reforms;

- The Child Nutrition Act of 1966, improving nutritional assistance to children and establishing the School Breakfast Program;

- The Civil Rights Act of 1968 (commonly known as the Fair Housing Act) extended constitutional protections to Native Americans, and prohibited all forms of housing discrimination based on race, color, religion or national origin. (Following the achievement of access to public accommodations in 1964, and the passage of the 1965 voting rights act, the civil rights movement had increasingly targeted housing discrimination as the next arena for comprehensive federal legislation, including Martin Luther King’s major 1966 campaign in Chicago. The Fair Housing Act was signed into law by President Johnson on April 11, 1968, just one week after Dr. King’s assassination on April 4, 1968.)

The Great Society civil rights and anti-poverty programs enjoyed broad and bipartisan support. Even as funding for the War on Poverty was undercut by the massive costs of the Vietnam War, important programs assisting the poor and unemployed expanded throughout the 1960s and early 1970s of the Johnson and Nixon Administrations.

The consolidation and expansion of Federal government programs to further economic equality and poverty alleviation continued until 1977, when President Carter signed into law the Food Stamp Act, which eliminated the previous requirement that recipients pay for food stamps, and established the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) which continues to provide a floor of support for millions of poor families who would otherwise struggle with hunger.

Ernest Withers, Sanitation Workers Strike, Memphis, 1968, Creative Commons

In this broader context of legislation enacted pursuant to President Johnson’s Great Society and War on Poverty initiatives, and the continued legacy of these transformative initiatives through the Nixon and Carter Administrations, we can review the specific employment related demands made by the 1963 March on Washington organizers and participants:

Demand for Fair Employment Practices legislation

In August 1963, the March demanded the enactment of “a federal Fair Employment Practices Act barring discrimination by federal, state and municipal governments, and by employers, contractors, employment agencies, and trade unions.” Congress heeded this call, enacting a broad federal prohibition against job discrimination as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Under Title VII, it is “an unlawful employment practice” for an employer: “(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin; or (2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or applicants for employment in any way which would deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employment opportunities or otherwise adversely affect his status as an employee, because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.”

For a critical analysis of the achievements and failures of Title VII over the subsequent six decades of Title VII enforcement, litigation and jurisprudence, with recommendations for reform, see Deborah L. Brake and Joanna L. Grossman, “The Failure of Title VII as a Rights-Claiming System,” 86 North Carolina Law Review (2008); Chuck Henson, “Title VII Works: That’s Why We Don’t Like It,” 2 UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI RACE & SOCIAL JUSTICE LAW REVIEW 41 (2012); Kimani Paul-Emile, “Beyond Title VII: Rethinking Race, Ex-Offender Status, and Employment Discrimination in the Information Age,” 100 Virginia Law Review (2014); Chuck Henson, “The Purposes of Title VII,” 33 NOTRE DAME JOURNAL OF LAW, ETHICS AND PUBLIC POLICY 221 (2019), and Paul W. Mollica, “The Unfinished Mission of Title VII: Black Parity in the American Workforce,” 23 Journal of Gender Race & Justice 139 (2020).

It took another four years for the Johnson Administration to propose comprehensive workplace safety legislation for American workers. The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1968 was introduced in both chambers of Congress. After two more years of legislative debate, the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970, signed into law by President Richard Nixon, created the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) “to ensure safe and healthful working conditions for workers by setting and enforcing standards and by providing training, outreach, education and assistance.” Another important legacy of the Great Society era, OSHA continues to provide American workers with lifesaving health and safety enforcement and protection today.

Demand for federal job training and placement

The Great Society legislation did include federal job training programs, coordinated through the new Office of Economic Opportunity, including the Jobs Corps and Neighborhood Youth Corps (NYC) discussed above. NYC served 200,000 young people in its initial months; by the end of 1968 the program had helped over 1.5 million. Still, the job training and placement legislation of the 89th Congress was far less comprehensive than the “massive” training and placement program demanded by Bayard Rustin at the March. Hubert Humphrey and other Senate liberals wanted to do more, combining legal requirements for fair and equal employment with a federal commitment to full employment.

“Beginning in May 1963, Senator Joseph Clark’s yearlong Senate Subcommittee on Labor and Public Welfare hearings on the “Manpower Revolution” uncovered widespread doubts that Kennedy’s economic and civil rights policies would address the structural roots of mass unemployment. Clark’s report proposed investing $5 billion a year in public works jobs for the most disadvantaged unemployed workers. Senator Hubert Humphrey incorporated most of Clark’s recommendations into S. 1937. But in the fall, to overcome the objections of Senate minority leader Everett Dirksen, Democrats dropped the Humphrey bill and stripped Title VII and the EEOC of powers to issue cease and desist orders against discriminating companies.”

Thomas F. Jackson, From Civil Rights to Human Rights: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Struggle for Economic Justice (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), pp. 170-171.

But this more comprehensive labor policy, in alignment with the demands made by Randolph, Rustin and King in August 1963, re-emerged with the eventual passage of the Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment Act. Signed into law by President Jimmy Carter on October 27, 1978, Humphey-Hawkins was arguably the last major initiative of an extraordinary experiment in social democracy created by the convergence of the March on Washington, the Black Freedom Movement more broadly, the progressive labor movement, the landslide victory of Lyndon Johnson over Barry Goldwater in the 1964 national election, and President Johnson’s launch of the Great Society and War on Poverty beginning in 1964 — an experiment that ended definitively with President Ronald Reagan’s insistence, in his January 20, 1981 inauguration, that “[g]overnment is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem.”

Demand for a decent standard of living for all American workers

Gathering at the Lincoln Memorial After Walking from Washington Monument Grounds

© Jim Wallace, National Museum of African American History and Culture

President Franklin Roosevelt promoted the idea of “fair labor standards”, including a national minimum wage, as a core element of the New Deal he had proposed to address the struggles of working people in the Depression. The process to enact a Fair Labor Standards Act was extremely contentious, involving vigorous opposition from business and comparably intense conflict within Congress, and between all three branches of the federal government regarding the power of the federal government to regulate private employers. FDR and Congress claimed authority for economic regulation pursuant to the “interstate commerce” clause of the Constitution (Article I, Section 8, Clause 3).