Note: This is an expanded version of a talk I gave to the Western Regional division of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA Region 9) on January 15, 2025. Following my remarks, it was a privilege to engage in a rich dialogue with a senior EPA officer and my USF colleague Philosophy Professor Ronald Sundstrom.

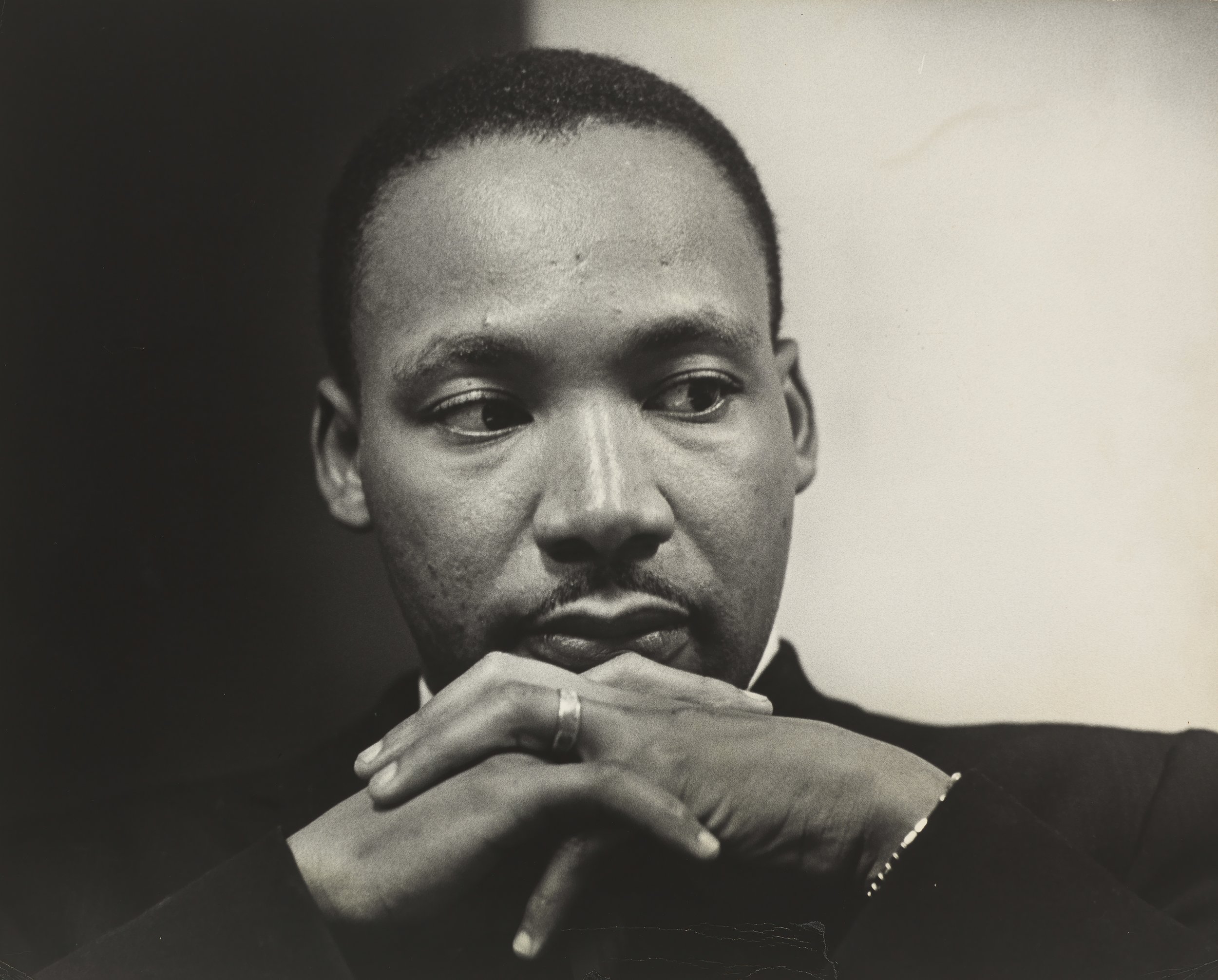

I am honored to speak with you today on Dr. King’s 96th birthday. I didn’t hesitate to accept this wonderful invitation because I believe that Dr. King would be proud to speak to you if he was still alive today. I believe that he would offer his deep support for the urgently important work of the EPA, all of your efforts to protect the health and safety of all Americans, especially right now, and am certain that he would offer his fierce support to each of you personally at this extremely challenging time.

I am mindful of our colleagues, friends and family in Los Angeles. My father and my brother are both evacuated. I’m certain that the fires have impacted everyone on this call from the EPA’s LA office, and that there has been great loss.

Dr. King came to Los Angeles in August 1965 when LA was on fire during the Watts rebellion. King called on the community to remain committed to nonviolence. But he emphasized that the problems that led to the riots exploded because of “economic deprivation, social isolation, inadequate housing, and general despair.” He said that we should understand these problems as “environmental and not racial.”

I’m here with you because I’ve had the extraordinary gift to know and work closely with Dr. Clarence B. Jones who served as personal lawyer, strategic advisor, and draft speechwriter to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on a 24/7 basis from 1960 until King’s assassination on April 4, 1968.

In 2008, Dr. Jones published a book called What Would Martin Say? Today, as we are surrounded by the fires of environmental damage and the fires of political nihilism, as our cities are ravaged by climate chaos and our democracy is ravaged by chaos and corruption, we ask ourselves the same question: what would Martin say to us today?

This is the question before us. What would Dr. King say to us, right now, in this perilous moment?

Of course it is not possible to know for certain. But we can find an answer as close and true to King as possible: by remembering and citing with accuracy what he said in times when facing darkness and depression, chaos and struggle, in his own adult life.

Dr. King was an ecological thinker and activist. Dr. King was assassinated on April 4, 1968. The word “ecology” did not become widespread until after the first Earth Day two years after King’s assassination in April 1970, just eight months before the EPA was founded.

But Dr. King was prescient in his analysis and prophetic in his words. He looked at the world from a moral and ecological perspective and he told us that the survival of humanity depended on all of us doing the same. He always fought for the health and safety of communities, especially those who are most vulnerable and marginalized, and he urged us to join him.

Biologists and geologists and atmospheric chemists hadn’t developed earth system science until years after Dr. King was assassinated, on April 4, 1968. I believe that, had King lived to be with us today, he would even more strongly offer an ecological understanding of the world fully aligned with earth systems science. Starting in the 1950s, Dr. King expressed concern for “the survival of the world,” and linked environmental and civil rights issues: “It is very nice to drink milk at an unsegregated lunch counter — but not when there’s strontium 90 in it.”

One of his most famous texts was the letter from a Birmingham Jail. 1963. Obsessed about the letter published in the local newspaper from leading ministers, priests and rabbis calling for the Black citizens of Birmingham to cease their protests. They accused Dr. King of being an outside agitator, and to leave town, so that the local people might solve their problems peacefully. This letter angered King, because it was written by the “well-meaning” liberal members of the white clergy, precisely the community members who should have supported him, and the black mass protestors, at this moment of crisis when Jim Crow segregation in Birmingham was challenged as never before.

This is from Dr. King’s letter:

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.”

Dr. King wrote this only a few months after the publication of Silent Spring. I don’t believe that King every met Rachel Carson. But I believe that the two figures shared an ecological vision of planetary interrelationships upon which life depends.

The remainder of my talk discusses what Dr. King meant by “the inescapable network of mutuality” and identifies several corollary ideas, central to Dr. King’s thinking, that flow from this core principle. I suggest these associated principles by referring to Dr. King’s own words.

Corollary 1: The local, the national and the global are all connected, and the struggle for justice and freedom must be fought at all levels.

“I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham…. Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial “outside agitator” idea. Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider.” Martin Luther King, Jr., Letter from a Birmingham Jail, 1963

Corollary 2: It is morally wrong to hide in silence and inaction when the human rights of others are being violated, even if they are far away.

Imploring us to understand that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” King was speaking literally.

The pain and suffering of others must become ours. If we ignore their suffering, the same violations will come to us and those we love.

King’s insight evokes the famous poem of the German Lutheran Pastor Martin Niemöller about the silence of his countrymen during the rise of Hitler and the crimes of Nazism:

“First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.”

The courageous Philippine and American journalist Maria Ressa shares the Nobel peace prize with Dr. King. Ressa suffered harassment, prosecution and threat of imprisonment for political crimes related to her journalism documenting human rights abuses of the regime of former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte. I recently had the privilege to meet her and hear her speak. Ressa gave her own version of the Niemoller poem, suggesting the critical importance of journalists who bravely report on injustice everywhere.

“First they came for the journalists. We don’t know what happened after.”

But we do know. We just don’t know the specifics.

Corollary 3: We have no personal enemies. Our enemies are injustice, systemic violence, and everything that debases human dignity and poisons life on earth.

Dr. King affirmed this principle throughout his ministry. But the person who most powerfully helped him to understand this distinction was the Vietnamese Buddhist teacher Thích Nhất Hạnh.

“The enemies of those struggling for freedom and democracy are not men. They are discrimination, dictatorship, greed, hatred and violence, which lie within the hearts of man. These are the real enemies of man—not man himself. Joint statement of Thích Nhất Hạnh and Martin Luther King, Jr., 1965

Corollary 4: We must abjure hatred

We must not allow ourselves to indulge in hate: because hatred is toxic — poisoning our souls, twisting our minds and blinding our eyes — and therefore harmful for us and counterproductive to our goals; because we have no personal enemies; because even our racist and violent adversaries can be converted into our allies in the long struggle to build the Beloved Community.

“I am aware of the fact that the vast majority of white persons of Montgomery and the state of Alabama sincerely believe that segregation is both morally and sociologically justifiable… We must continue to believe that the most ardent segregationist can be transformed into the most constructive integrationist…”. Martin Luther King, Jr., “Facing the Challenge of a New Age,” Address Delivered at the First Annual Institute on Nonviolence and Social Change, 3 December 1956

We need not hate; we need not use violence. We can stand up before our most violent opponent and say: We will match your capacity to inflict suffering by our capacity to endure suffering. We will meet your physical force with soul force. (Make it plain) Do to us what you will and we will still love you. Martin Luther King, Jr., “The American Dream,” Ebenezer Baptist Church, July 4, 1965

Corollary 5: We must commit ourselves to nonviolence as our strategy, our way of resolving conflict and our way of life.

“There is another method which can serve as an alternative to the method of violence, and it is a method of nonviolent resistance…. This method is nonaggressive physically but it is aggressive spiritually… [T]he nonviolent resister seeks to change the opponent, to redeem him. He does not seek to defeat him or to humiliate him. And this is very important, that the end is never merely to protest but the end is reconciliation… And so the aim must always be to defeat injustice and not to defeat the persons who are involved in it. This method of nonviolence seeks to win the friendship and the understanding of the opponent… Another basic factor in the method of nonviolent resistance is that this method does not seek merely to avoid external physical violence, but it seeks to avoid internal violence of spirit. And at the center of the method of nonviolence stands the principle of love… “ Martin Luther King, Jr, “Non-Aggression Procedures to Interracial Harmony,” Address Delivered at the American Baptist Assembly, 23 July 1956.

“Nonviolent resistors can summarize their message in the following simple terms: we will take direct action against injustice without waiting for other agencies to act. We will not obey unjust laws or submit to unjust practices. We will do this peacefully, openly and cheerfully because our aim is to persuade. We adopt the means of non-violence because our end is a community at peace with itself. We will try to persuade with our words, but if our words fail, we will try to persuade with our acts. We will always be willing to talk and seek compromise, but we are ready to suffer when necessary and even risk our lives to become witnesses to the truth as we see it. I realize that this approach will mean suffering and sacrifice. It may mean going to jail. If such is the case the resistor must be willing to fill the jail houses of the South. It may even mean physical death. But if physical death is the price that a man must pay to free his children and his white brethren from a permanent death of the spirit, then nothing could be more redemptive. This is the type of soul force that I am convinced will triumph over the physical force of the oppressor.” Martin Luther King, Jr, ““The Rising Tide of Racial Consciousness,” Address at the Golden Anniversary Conference of the National Urban League, September 6, 1960

“For we’ve come to see the power of nonviolence. We’ve come to see that this method is not a weak method, for it’s the strong man who can stand up amid opposition, who can stand up amid violence being inflicted upon him and not retaliate with violence (Yeah) [Applause]. You see, this method has a way of disarming the opponent. It exposes his moral defenses. It weakens his morale, and at the same time it works on his conscience, and he just doesn’t know what to do.” Martin Luther King, Jr., Freedom Rally in Cobo Hall, Detroit Michigan, June 23, 1963

Corollary 6: We must oppose militarism, resist war, and withdraw our cooperation from systems of organized violence.

“There is a voice crying through the vista of time saying, ‘He who lives by the sword will perish by the sword.’ (Matthew 26:52). And history is replete with the bleached bones of nations who refused to listen to the words of Jesus at this point. The method of violence would be both impractical and immoral. If this method becomes widespread, it will lead to terrible bloodshed, and that aftermath will be a bitterness that will last for generations.” Martin Luther King, Jr, “Non-Aggression Procedures to Interracial Harmony,” Address Delivered at the American Baptist Assembly, 23 July 1956.

“First of all, we must resist war. With all our energy we must find our alternative to violence as a means to deal with the terrible conflicts conflicts that beset us. We must no longer cooperate with policies that degrade man and make for war. As you know, the establishment of social justice in our nation is of profound concern to me. This great struggle is in the interest of all Americans, and I shall not be turned from it. Yet no sane person can afford to work for social justice within the nation unless he simultaneously resists war and clearly declares himself for nonviolence in international relations.” Martin Luther King, Jr., “Address at the Thirty-sixth Annual Dinner of the War Resisters League,” February 1959

Corollary 7: We must work without cease to prohibit nuclear testing and abolish nuclear weapons.

Speaking with a high level of scientific understanding, King called to rid our nation and the world of nuclear weapons. Escalating the nuclear arms race, “we’ve played havoc with the destiny of the world,” he warned. He understood the problem of nuclear warfare to be the destruction of our sacred planet, the human communities that dwell in cities and rural areas, and all species and life on earth. As a result, King’s larger ecological commitment was greater than his dedication to civil rights.

“What will be the ultimate value of having established social justice,” he asked, “in a context where all people, Negro and White, are merely free to face destruction by strontium 90 or atomic war.” Martin Luther King, Jr. “Address to the War Resisters League,” February 1959

This is Dr. King’s response to a question addressed to him in an “Advice for Living” column he wrote in December 1957:

“Question: Do you believe that the development and use of nuclear weapons of war should be banned?”

“Answer: I definitely feel that the development and use of nuclear weapons of war should be banned. It cannot be disputed that a full scale nuclear war would be utterly catastrophic. Hundreds and millions of people would be killed outright by the blast and heat, and by the ionizing radiation produced at the instant of the explosion. If so-called “dirty bombs” were used, large areas would be made uninhabitable for extended periods of time, and additional hundreds and millions of people would probably die from delayed effects of local fall-out radiation—some in the exposed population from direct radiation injury and some in succeeding generations as a result of genetic effects. Even countries not directly hit by bombs would suffer through global fall-outs. All of this leads me to say that the principal objective of all nations must be the total abolition of war. War must be finally eliminated or the whole of mankind will be plunged into the abyss of annihilation.”

And this is his from his Easter Sunday sermon at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Montgomery Alabama, on March 29, 1959

And before there can ever be peace in this world, we must turn to an instrument like the United Nations and disarm the whole world and develop a world police power so that no nation will possess atomic and hydrogen bombs for destruction. This is our hope, isn’t it? It was buried one day, but now it has been resurrected.

In a day when Sputniks and Explorers dash through outer space and guided ballistic missiles are carving highways of death through the stratosphere, nobody can win a war. Today the choice is no longer between violence and nonviolence. It is either nonviolence or nonexistence.

Corollary 8: We must reject sectionalism and dedicate ourselves to a global vision

All of these themes come together in Dr. King’s final Christmas sermon at the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta Georgia, Christmas 1967:

“If we are to have peace on earth, our loyalties must become ecumenical rather than sectional. Our loyalties must transcend our race, our tribe, our class, and our nation; and this means we must develop a world perspective.”

Again the same language from his 1963 Letter from a Birmingham Jail, with his fundamental ecological perspective even more clearly expressed:

“It really boils down to this: that all life is interrelated. We are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied into a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. We are made to live together because of the interrelated structure of reality.”

During Dr. King’s life and ministry, scientists had not yet reached a comprehensive understanding of the harmful greenhouse effects resulting from a global energy system dependent on the massive extraction and burning of fossil fuel. Had Dr. King not been murdered in 1968, I strongly believe that Dr. King would have been a leader in the movement for environmental justice that emerged in the 1970s and beyond. His ultimate concern was for the survival of the world. Our interconnected networks of mutuality creates the structure of reality. This requires us to restrain the toxic impacts of industrial production, to clean up sites that have been polluted by harmful chemicals and waste, to hold accountable those responsible for poisoning our air and water, and to enforce laws and regulation designed to protect the health of all people and all living things.

Without legislation and regulation protecting the environment, and without the tireless work of the EPA and all of its scientists and staff, we are playing havoc with safety and wellbeing of our communities, especially those who are most marginalized and most frequently exposed to noxious harm, and we are playing havoc with the destiny of the world.

The title of Dr. King’s last book, published in 1967, asks a question that remains the most important question for us today: Where do we go from here?

Dr. King answered this question perhaps most clearly in his “Beyond Vietnam” speech, delivered at the Riverside Church in New York City on April 4, 1967, exactly one year before he was killed. “We as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values,” he said.

“We must rapidly begin…we must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered…. Our only hope today lies in our ability to recapture the revolutionary spirit and go out into a sometimes hostile world declaring eternal hostility to poverty, racism, and militarism.”

Last year we lost Rev. James Lawson. Rev. Lawson was the immensely gifted visionary teacher who trained John Lewis and all of the Nashville students in nonviolent civil disobedience. Along with Bayard Rustin, Lawson is the person who brought Gandhian nonviolence to Dr. King, to the student activists who sat in at the lunch counters and rode the buses throughout the South as Freedom Riders, and to Dr. King himself.

Rev. Lawson didn’t use the term “civil rights movement.” He spoke of the “nonviolent movement for America” of which Martin King remains the most iconic and inspiring leader. The nonviolent movement of America includes countless grassroots campaigns that make up the the Black Freedom Movement and Black Lives Matter, and the movement for housing rights and welfare rights, the industrial labor movement and the movement for the rights of farmworkers and refugees, the women’s movement and the movement for LGBTQ rights, the movement against the war in Vietnam and the movement against the war in Iraq, and the movement for human rights everywhere. The nonviolent movement of America very much includes the environmental movement, from the campaigns for nuclear disarmament in which Martin and Coretta King were global leaders, to the first Earth Day in 1970, just two years after Dr. King’s assassination, to the countless local campaigns to stop the pollution of urban and poor rural communities, to clean up toxic sites, to stop unsafe oil and gas drilling and pipelines, and to push for action necessary to address the threat of catastrophic climate change.

These movements led to great legislative achievements, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Fair Housing Act of 1968, the founding of the EPA in 1970, the Clean Air Act of 1970, the Clean Water Act of 1972, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009, the climate change measures in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, among others. But this list of achievements is not enough. Nowhere near enough. And the achievements since 1972 are few and far between. We have been stuck in partisan battles that have blocked progress for most of the past half century. And we have so much work to do. The John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2021 remains blocked; the Equal Rights Amendment remains blocked; the rights of women, workers, immigrants are under threat; the entire federal civil service is under threat, including the incredible scientists, engineers, administrators, and staff of the EPA; the agencies created to regulate the excesses of corporate power are under threat, including the EPA itself; the integrity of our federal law enforcement system is under threat; and the actions we need to reform our energy system are woefully inadequate to address the climate emergency we face here in California, as a nation and global community.

I believe that Dr. King is here with us, encouraging and supporting us giving us hope, as we continue the hard and necessary work to revitalize and re-energize, mobilize and intensify of the nonviolent movement of movements to redeem the soul of America, to save our democracy, to secure human rights for all people, to protect the most marginalized communities, and to ensure the survival of our planet Earth.

Jonathan D. Greenberg