Young Woman with Banner, March on Washington for Jobs & Freedom, 28 August 1963

Photograph by Rowland Scherman, Wikimedia Commons

Sixty years ago today, on August 28, 1963, 250,000 people gathered in Washington DC for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. They came by car, by bus, by train. Some walked, over days. They came to send a message to the nation, a message summarized by Sam Cooke shortly after: “It’s been a long, a long time coming/But I know a change gonna come.”

Clarence Jones, today

Many readers of this Fierce Urgency blog know Clarence B. Jones, founding director emeritus of the USF Institute for Nonviolence and Social Justice. You know about his work with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., as Dr. King’s lawyer, strategic counsel, and draft speechwriter, through all of the struggles of the 1960s until Dr. King’s assassination on April 4, 1968.

As you can imagine, this has been a heady week for Dr. Jones, full of memories and emotions.

Sixty years ago, standing near the podium at the Lincoln Memorial while Dr. King delivered his iconic speech, Dr. Jones was startled to realize that Dr. King was using the text he had prepared to frame his remarks. Then he heard Mahalia Jackson call out “Tell ’em about the dream!” and he saw Dr. King put aside his written text and begin to riff extemporaneously to inspire the nation with his dream.

Today, sixty years later, Dr. Jones is the only surviving participant in the planning of the March. Bayard Rustin and A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins and Whitney Young, Jr., James Farmer and John Lewis, they are not here with us any more.

Because of the historic role Dr. Jones played in the 1963 March, Dr. Jones has been featured in articles, interviews and op-eds published by major newspapers, magazines, TV and radio programs over the past few days, including The Guardian, Washington Post, CNN, The Forward, Boston Globe, All Things Considered, USA Today, and the Rev. Al Sharpton’s “Politics and Nation” show on MSNBC.

It is moving to witness the recognition Dr. Jones is receiving at this time, sixty years later, honoring his service to Dr. King, to the Black Freedom Movement, to our nation, and to all of us.

Surrounded by ghosts, dreams and nightmares, we too remember the March and reflect on its meaning, in history and for America today.

Malcolm X, 1964, Library of Congress, Public Domain

With his signature lacerating sarcasm, Malcolm X derided the March and its organizers — before, during and after the big day. For Malcolm it was “the Farce on Washington,” “a picnic” and “a circus” — a national spectacle of accommodation to the white power structure. “I was impressed the same way I would be with the Rose Bowl game, the Kentucky Derby, and the World Series,” he said, suggesting that President John F. Kennedy “should get Academy Awards for directing the best show of the century.”

Was Malcolm right?

Was it a picnic? Yes — March organizers had to feed 250,000 people, somehow. The National Council of Churches made and distributed 80,000 box lunches — a good start. Another 170,000 brought their own sandwiches (instructions urged people not to use mayonnaise which could get spoiled by the hot sun) or picked up food from local vendors. This was before the era of the plastic water bottle, so workers had to install hundreds of drinking fountains to keep the people hydrated in the stifling heat and high humidity.

Was it a circus? There were no acrobats or elephants. No clowns — but Dick Gregory made thousands laugh. As usual, =his comedy “struck a blow to the heart of racism.” “It’s a pleasure being here and nice being out of jail,” he told the crowd. “And to be honest with you, the last time I’ve seen this many of us, Bull Connor was doing all the talking.” Just weeks before Gregory had gone to Birmingham and marched and went to jail there, and told the crowd of protestors upon his release:

“I don’t know how much faith you have in newspapers, but I read an article in the paper a couple days ago, where the Russians – did you see this, they gave it a lot of space – the Russians claim they found Hitler’s head. Well I want to tell you that’s not true. You want to find Hitler’s head, just look right up above Bull Connor’s shoulders.”

Was the March the best show of the century? Perhaps it was. More so than the Rose Bowl game, more so than the Kentucky Derby, more so than the World Series, more so than the Academy Awards.

The March created the first “national stage” of the modern televised era, and harnessed multiple streams of American artistic expression that had not previously been brought together: the deep tradition of Black spiritual and gospel music (Mahalia Jackson), choir music from the Harlem Renaissance (Eva Jessye), jazz cabaret (Josephine Baker), blues (Odetta) and opera (Marian Anderson); the new folk music balladeers (Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Peter Paul & Mary), and the Black Freedom Singers of the Southern civil rights movement; and mainstream Hollywood celebrity culture (the so-called “celebrity contingent” including Harry Belafonte, Charlton Heston, Marlon Brando, Steve McQueen, Diahann Carroll, Sidney Poitier, Sammy Davis, Shelley Winters, Burt Lancaster, Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward). Precisely at the moment when TVs became ubiquitous in American households (with over 90% of U.S. households having one), the March was broadcast into millions of homes by all three TV stations (ABC, CBS, NBC) in live coverage throughout the entire day, with highlights re-broadcast in the evening news.

But Malcolm was wrong to suggest that President Kennedy deserved an Academy Award for directing it. On the contrary, Kennedy did his best to stop the March from happening. Two months earlier, John and Robert Kennedy convened a meeting of Black civil rights leaders, asking them to support his proposed civil rights legislation by refraining from protests, especially protest aimed to reach a national audience. “We want success in Congress,” the president told them. Ironically echoing Malcolm, he advised the leaders against making “a big show at the Capitol” — a show that could agitate legislators who might otherwise be his allies. “Some of these people are looking for an excuse to be against us. I don’t want to give any of them a chance to say, ‘yes, I’m for the bill but I’d be damned if I will vote for it at the point of a gun.”

In sum, Kennedy warned the Black leaders that the proposed March on Washington would be “a great mistake” he urged them to refrain from making. But Martin Luther King, Jr. declined the president’s counsel. “It may seem ill-timed,” he said. “Frankly, I have never engaged in any direct action movement which did not seem ill-timed.”

Planning for the March went forward, but the numbers of people gathered in Washington vastly surpassed even the highest aspirations of the organizers, led by the elder statesman A. Philip Randolph, leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (who had developed the idea of the March from its origins in the 1941 “Double V” campaign — victory against racism at home as well as abroad — a threat that pressured FDR to desegregate the war industries) and the socialist Gandhian Bayard Rustin, who somehow combined deep intellectual and spiritual commitment to nonviolence, relentless effort, and brilliant skills in strategic organization and operational logistics. Under the leadership of Randolph and Rustin, the March organizers created the national spectacle Kennedy had advised against, without igniting a powder keg of violence as the white power structure had feared. The result was indeed an unprecedented cultural show of force. More importantly, March organizers mobilized an astonishing political show of force.

Randolph and Rustin, in coordination with local community leaders and Black activists throughout the south, and clergy and congregants throughout the country, brought together for the first time Southern and Northern civil rights and interfaith religious organizations in the greatest political demonstration ever assembled. Randolph and Rusin brought together the anti-racist wing of the U.S. labor movement, including the powerful union leader Walter Reuther (President of the UAW, AFL-CIO), and they mobilized the leadership of the mainstream civil rights organizations (Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, Whitney Young of the National Urban League), the Black clergy of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (led by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.), the nonviolent leaders of the Freedom Rides (including James Farmer of the Congress of Racial Equality, and John Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, representing what Dr. King called “the marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community”. Key to the March’s success was the assembly of intergenerational, interracial, and interfaith coalitions, including mainstream religious organizations and leaders including the Very Rev. Patrick O’Boyle, Archbishop of Washington, rabbis and ministers from congregations across the country, and a huge turnout from the National Council of Churches.

What was the March?

Robert Joyce papers, 1952-1973, Historical Collections and Labor Archives

Special Collections Library, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University.

As Randolph told the crowd, this was “the largest demonstration in the history of this nation.” And “we are the advance guard of a massive moral revolution for jobs and freedom.” In this revolution, “[t]he sanctity of private property takes second place to the sanctity of the human personality.”

In Montgomery, Albany, Birmingham, in local struggle after local struggle, the locus of political activity was the mass meeting, held at a Black church in the community. In Washington D.C., organizers created a gigantic mass meeting in the nation’s capital.

It was a faith gathering of all faiths. It was largest racially integrated assembly in US history.

It was the largest labor rally ever held, a march for full employment for everyone, a living wage for all workers, quality education for all children, affordable housing for all families, and racial equality for all Americans.

Its goal was conversion — to win white America over to the Black struggle in the South, to redeem the conscience and soul of the nation.

To generate enough political force to pressure the Kennedy Administration and Congress to secure greater, more ambitious, more expansive achievements to overcome Jim Crow and bring about economic justice than would otherwise have been possible.

Bookended by violence — the assassination of Medgar Evers in Mississippi in June, the murder of the four schoolgirls in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in September — the March on Washington was a powerful demonstration of Gandhian nonviolence, a military operation of the largest nonviolent army ever assembled in the United States, the most important operation in a larger nonviolent war: transforming local campaigns in Southern cities into a national movement to overthrow Jim Crow system, secure the rights promised in the !4th and 15th amendments, and to achieve a moral revolution in America akin to the second reconstruction.

See Russell Baker, “Capital is Occupied by a Gentle Army,” New York Times, August 29, 1963.

Interviewed on national television on August 28 1963 after the March, Dick Gregory said: “As long as a man alive on the face of this earth, this day will be remembered the world over.”

The bank of justice

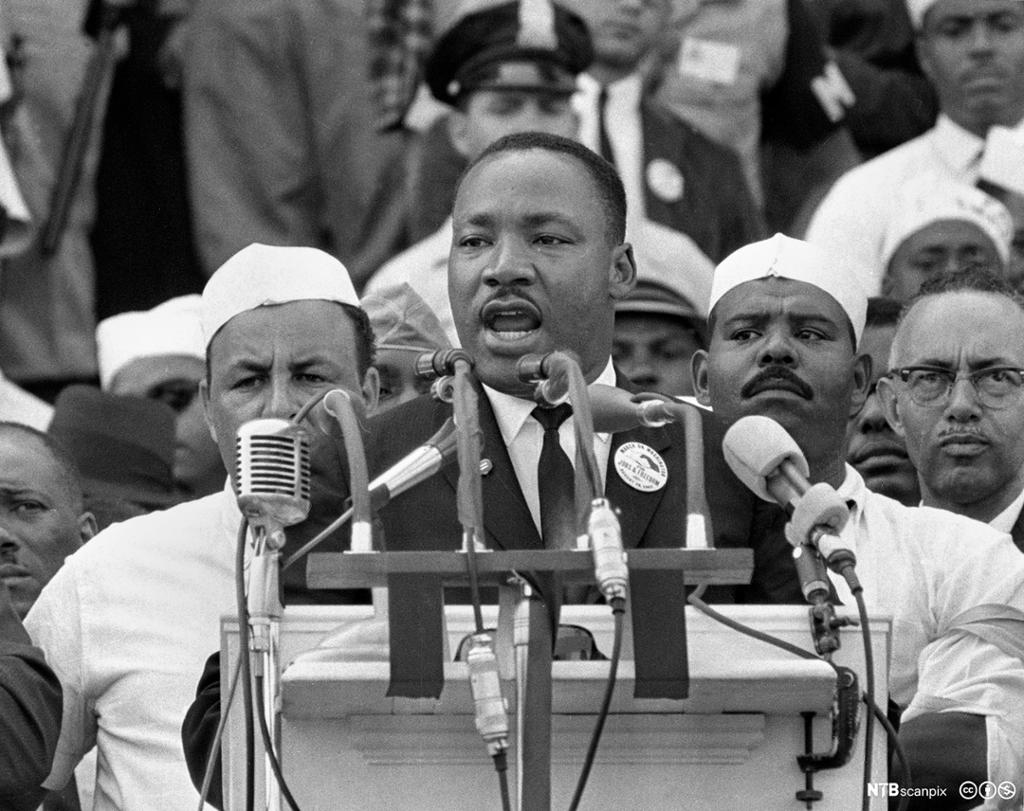

Dr. King at the March on Washington, 1963, Creative Commons.

Above all, we remember Dr. King’s stirring dream. But the first half of Dr. King’s speech, written by Clarence Jones, is no less powerful, and no less important today.

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land. And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition. In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check.

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men — yes, Black men as well as white men — would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt.

We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

We have also come to his hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism.

Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.

Photograph by Paul Ryan

Jonathan D. Greenberg

References and further reading

Russell Baker, “Capital is Occupied by a Gentle Army,” New York Times, August 29, 1963.

Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63 (Simon & Schuster, 1988).

Jonathan Eig, King: A Life (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023).

Clarence B. Jones and Stuart Connelly, Behind the Dream: The Making of the Speech that Transformed a Nation (Palgrave MacMillan, 2011).

William P. Jones, The March on Washington (Norton, 2013).

Peniel E. Joseph, The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. (Basic Books, 2020), pp. 152, 158-161, 164, 167.

Paul Kix, You Have to Be Prepared to Die Before You Can Begin to Live: Ten Weeks in Birmingham that Changed America (Celadon, 2023).

John Lewis, Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell, March: Book Two (Top Shelf/IDW Publishing, 2015).

Thomas E. Ricks, Waging a Good War: A Military History of the Civil Rights Movement, 1954-1968 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022).

Gary Younge, The Speech: The Story Behind Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Dream (Haymarket, 2013).