What is reparative and inclusive description, and why does it matter? How can libraries and archives use collections description to pursue social justice? Zoe Hume, inaugural Reparative and Inclusive Description (RID) Survey Scholar, shares her answers to these questions and reflects on her experiences at Gleeson Library | Geschke Center.

If you had to sum up your life in a handful of keywords, could you? Now imagine those keywords are not in your language or there is no word for something you think of as crucial to your sense of self. Imagine the only words to describe your life are patronizing or offensive or even outright slurs.

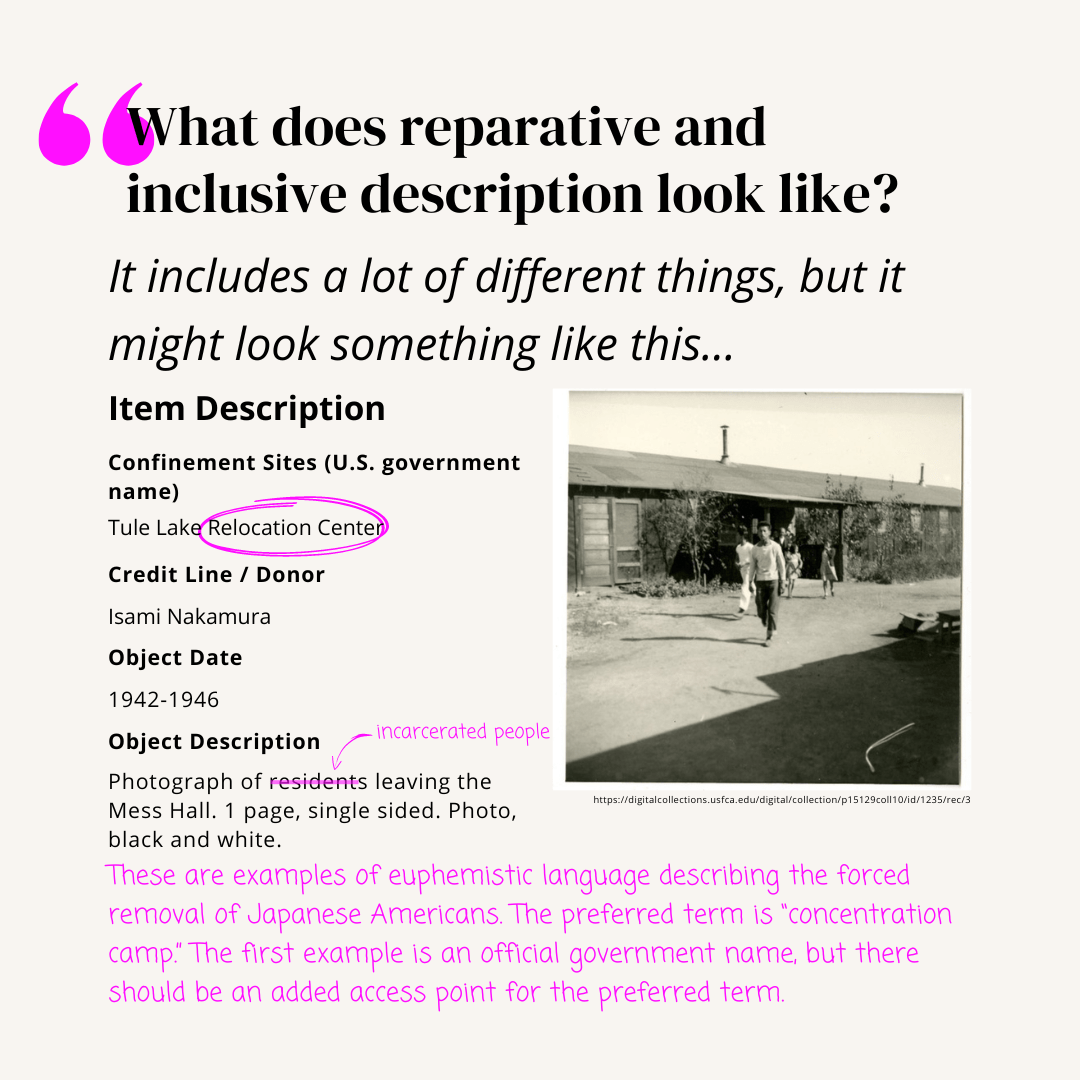

Cataloging and classification are tricky things. They are the backbone of libraries and archives, yet descriptive work happens behind-the-scenes. Librarians and archivists organize knowledge to help people find it, but in doing so they make strategic decisions about what gets highlighted and what gets minimized (or even erased) in their systems. Most of the time, they rely on controlled vocabularies and classification systems to make these choices. Yet, the beliefs of the time undeniably influenced the original creators of these vocabularies and systems.

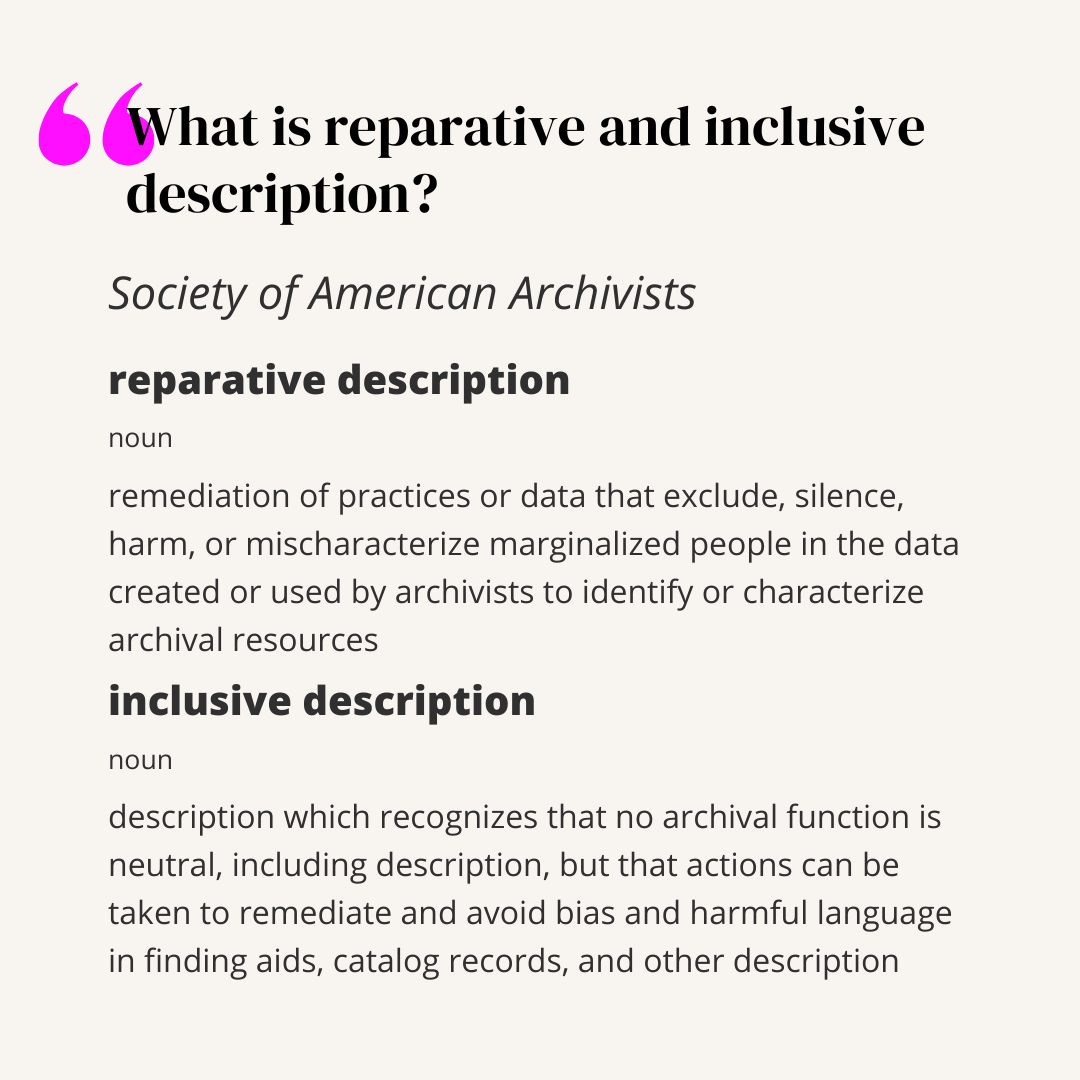

Reparative and inclusive description are tools for addressing the ways past and present descriptive practices fail to respect marginalized histories and communities. Bergis Jules called this a “failure of care around the legacies of marginalized people” and urged librarians and archivists to confront “the unbearable whiteness” of the information profession. As Michelle Caswell points out, oppressive structures feel inescapable, and they’re meant to feel that way, but there is always a way out. It is through naming white supremacy and other oppressive ideologies that we can begin to dismantle these ideologies and address our failures of care.

As the inaugural Reparative and Inclusive Description (RID) Survey Scholar, this semester I took a deep dive into the literature informing this work, adding 78 entries to an annotated bibliography! Many theoretical positions guide reparative and inclusive description, including Indigenous ways of knowing, queer theory, critical race theory, feminist ethics of care, and more. Under the guidance of Annie Reid (University Archivist) and Justine Withers (Electronic and Continuing Resources Catalog Librarian), I engaged in weekly critical reflections on these theories and on the best practices in reparative description. Together, we took the valuable time and space to not only grapple with the complexities of redescription but also consider how theory should inform practice.

I also completed several shorter projects, including a review of Gleeson Library’s Harmful Language Statement and other departmental documents regarding subject heading changes. During these reviews, I asked questions, made comments, and offered suggestions for ways to improve workflows and clarify technical or logistical issues. These projects encouraged me to think about the administrative structures in which all cultural heritage services operate. As much of the literature points out, issues with descriptive practice are ultimately embedded in the institution’s fabric, which means we must acknowledge colonial structures and keep them in mind (rather than trying to ignore them) as part of tearing them down.

Other projects I completed include reviewing the Woman’s Suffrage Collection Finding Aid and making recommendations for reparative description, surveying digital collections and suggesting methods for uncovering harmful content and guidelines for responding to harmful digitized content, and drafting content warnings for digital resource collections. Through these projects, I engaged with key elements of reparative and inclusive description and helped shape a Gleeson-specific understanding of what the theoretical work supporting these projects looks like in practice.

One of the most impactful practices Justine, Annie, and I explored was trauma-informed memory work. Looking back on my previous experiences in archives, I can immediately call up memories of encountering harmful content. I can remember a World War II-era letter, sent from sister to brother overseas, wherein the author condemns the comparison of the plight of Black people in the United States to Jewish people on the Continent because, to paraphrase, Black people have a limited capacity for suffering. While looking through digitized newspaper records at Gleeson, I came across other anti-Black materials, including some that expressed similar sentiments about the mental capacity of Black people.

I could continue listing experiences, but they would all only underscore the point that I will carry these experiences with me throughout my career. These experiences made me angry and sad, and they continue to do so when I reflect on them, but they also help me understand why the field of memory work must consider how it can traumatize (and re-traumatize) both visitors and staff.

If you don’t feel like a place is “for you,” then why would you want to go there? It’s important to feel that your identity is respected, and catalogs do this through their descriptive practices. Libraries, archives, and museums all contain materials that capture someone’s history. If you can understand that the way you describe that history can affect how someone thinks about themselves, then it should be clear why it’s necessary to stop describing people in ways that will hurt them. If cultural heritage institutions truly want to be people-centered, it only makes sense for them to think about the ways they might hurt or traumatize the people they want to center.

It has been an honor being the inaugural RID Survey Scholar, and I am proud to have joined the Gleeson | Geschke family as they work to ensure their metadata is more equitable and honors the rich diversity of life. Though currently a museum education PhD student, my roots are in the library, and my time with Gleeson has been invaluable in my goal of bringing together the tools and knowledge from both worlds to pursue social justice in memory work and cultural heritage.

On November 14th, 2022, I made a collaborative post between the Gleeson Library and Florida State University Department of Art Education Instagram accounts discussing my internship (pictured above).