After greeting the former student, I described how Ron regularly came into my office to graze my books, ask about topics on which he was uninformed, and often would walk away with a book to read which, at a later date he would return, expecting a full conversation on the book’s contents. Ron’s choices often surprised me, I explained to the student since he was a hardcore empiricist and social scientist, and I was a lyrically inclined professor of humanities. Intrigued by my comments, the former student asked permission to take photos of my bookshelves and after he had done so, went into Ron’s office and methodically took photos of all the books his revered former professor had on his shelves.

I can think of no greater tribute to a mentor than to explore his mind through what he had read or might read. This former student’s reverence for Ron’s library and Ron’s reverence for mine illustrates an important feature of how we approach management education—in for-profit, non-profit, and public sectors—at the University of San Francisco. We recognize that reading widely, especially outside of one’s field and in literary modes that stimulate creativity, benefits the practice of management and life, even to the highest levels of practice, as demonstrated by Barack Obama’s conversation about literature with Michiko Kakutani of the New York Times.

The value of coming to the practice or study of management with a liberal arts education has been enthusiastically endorsed as preparation for leadership by recognized sources in the field, academic and popular. From the Harvard Business Review to Forbes, the Wall Street Journal to The Atlantic, educators are appreciating that exposure to the humanities provides students the skills necessary to succeed in managerial settings:

- How to hone powers of observation and to reflect—to study and analyze events, objects, and people;

- How to explore and manipulate big concepts and complex contexts but not get lost in the abstract;

- How to apply new ways of thinking to difficult problems that can’t be analyzed in conventional ways;

- How to communicate with diverse constituencies with persuasive and cogent arguments.

Skilled cultural interpreters who are well-read across the humanities can also recognize traits necessary for a successful managerial point of view, including an ability to tolerate ambiguity, recognize multiple perspectives, and proceed with an open-ended vision; an interpretive posture that is crucial for facing a murky future or tricky problems in a managerial setting.

For example, when teaching a case study in ethics courses for both MBA and MPA students, I ask students to follow the same steps a reader would follow analyzing a narrative or lyric:

- Where and when did the event occur? How is the stage set and the action determined? (business environment, and other details/setting)

- What happened? (outline of the action/plot)

- Who was involved? How do their points of view differ? (roles/positions and attributes of those involved/character)

- Why were the key decisions made and what were those decisions? (problem-solving methods/plot development)

- Which ethical considerations were taken into account? What recurrent themes or values surface in dialogue or behavior? (interests of people affected by the decision, relevant professional standards, theories, principles/themes)

- What course of action was decided on, and why? (including any ethical justification that was given/resolution of conflict)

I would then ask students to provide a summary of their experience and to reflect on what they and/or others (including multiple stakeholders) learned from these events. Was the decision taken virtuous? Would different actions lead to different outcomes? Might the characters have acted differently if they had known what the outcome would be? Did the events lead to any changes in duties, policies, or procedures?

In a September 2016 issue of Academy of Management Learning and Education, Christopher Michaelson supports the approach I take when he argues that those teaching ethics in business schools should consider using novels as required, indeed core reading for their students. He bases his recommendation on the premise that narrative pedagogy cultivates better businesspeople who have not only better skills but better characters and are employees who operate with more “enduring ethical effectiveness.” Michaelson characterizes the narrative approach to teaching ethics as shifting the primary question asked from “What should I do?” to “How should one live?” The question changes not just in direction but scope, from the immediate and individualistic request for a specific answer to a more general human consideration of moral conduct.

Thus, changing along with curricula supported by emerging research is the growing recognition that reading great works in the humanities can promote one’s ability to imagine and understand things from someone else’s perspective and, in turn, to grow in one’s career and personal life. Several Wall Street Journal items highlight the benefits of reading literature for managers. In “Why Good Storytellers are Happier in Life and Love,” a contributor writes that, “research shows that the way people construct their individual stories has a large impact on their physical and mental health. People who frame their personal narratives in a positive way have more life satisfaction.” Another item focuses on how one acquires those storytelling techniques, building basic social skills that reading fiction develops as outlined in a study published online in Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience.

Beyond the benefit in terms of enhanced “social skills,” however, reading creative writing can lead to deeper, more empathetic engagement with others that do not simply avoid the awkward (in the way that obeying the external control of the law is the mere minimum for moral conduct), but actively seeks to understand people, to develop empathy. As explained by David Brendel, in a survey where business executives rated empathy and intellectual curiosity as among the five most important skills for success in a digitized and global economy, in which many of our business partners are never in our physical presence. “In order to serve the needs of clients and colleagues around the world,” Brendel writes, “we must be adept at understanding their feelings, thoughts, and points of view” that is promoted by “reading the humanities.”

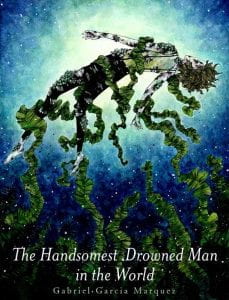

Taking a cue from the poet Mary Oliver who observed, “Attention without feeling is only a report,” let me walk you through some of the virtues of reading Gabriel Marquez’s story, “The Most Handsome Drowned Man in the World,” as part of a management curriculum. This simple but potent tale illustrates how a community uses imagination to resolve a potentially fearful mystery and the multiple ways those imaginative responses manifest in their lives. What is undeniable in the plot trajectory is how the characters’ capacity for moral conduct grows as they exercise the ability to tolerate mystery, to choose the good, and to create beauty while explaining an actual event and imagining a better life.

“The Most Handsome Drowned Man in the World,” tells the tale of a small, coastal fishing village interrupted by the arrival of a dead body washed up by the waves. This drowned man has a huge impact on the village, which is changed forever by his arrival. Characters move from a resigned complacency to an irritated curiosity and eventually to a creative vision inspired by an over-sized, exotic, washed-up corpse. As we watch the transformation in the townspeople, we are led to consider our own communities and how we lead our life, who inspires us, and how we handle the challenges of forces society and nature.

“The Most Handsome Drowned Man in the World,” tells the tale of a small, coastal fishing village interrupted by the arrival of a dead body washed up by the waves. This drowned man has a huge impact on the village, which is changed forever by his arrival. Characters move from a resigned complacency to an irritated curiosity and eventually to a creative vision inspired by an over-sized, exotic, washed-up corpse. As we watch the transformation in the townspeople, we are led to consider our own communities and how we lead our life, who inspires us, and how we handle the challenges of forces society and nature.

“The Handsomest Drowned Man in the World” opens with a group of children playing on the beach of a small fishing village. In the waves, a “dark and slinky” bulge is approaching and creating a tone of doom. It turns out to be a drowned man, covered in seaweed, stones, and dead marine creatures. The men head to neighboring villages to see if the dead man belongs to one of them, while the women clean off the body and prepare it for a funeral. “They didn’t have to clean his face to know that he was from elsewhere,” they live so remotely. The coastal, cliff-side town was a “desert-like cape” “with no flowers,” and so little land that the inhabitants have to throw their dead over the cliffs and into the sea rather than bury them in the ground, thus the curiosity arises more out of the identity of the body than its presence. While the women work on the drowned man’s body, as they imagine the “far-off seas and deep waters,” from which he came, they quickly assert, breathlessly, that he is the biggest, strongest-looking, most virile, and handsomest man they have ever seen in their lives, so remarkable “he didn’t even fit in their imaginations.” But his arrival triggers their imaginative capacity and they conclude that he died a “death with dignity,” is named Esteban, and when the men return with the news that no neighboring towns can claim him, the women weep with joy that he is now “theirs.”

The men don’t understand what all the fuss is about until the women show them the drowned man’s face. Then they, too, are in awe at his handsomeness, his masculinity, and his size. While they admire the drowned man, they think that he must have been ashamed of his size in life and must have felt awkward on account of it. “Fascinated by his disproportion and beauty,” the men respect him; but more than that, they become empathetic to his challenges and join the women and care for Esteban, attention that triggers care for each other as “the first cracks of tears opened in their hearts.” As Esteban comes alive to the villagers, so do they come alive to each other.

Together, the villagers prepare a splendid funeral for the drowned man. When they finally let his body go over the cliff and back to the waves below, they all know that their lives have been permanently changed and that they “were not complete, nor would they ever be again,” with Esteban gone. As they “shuddered to the marrow with the sincerity of Esteban,” his spirit remains an inspiration to expand their vision and improve their lives. The villagers know that they will build their houses stronger and bigger, to be big enough for a man like Esteban. They will paint their walls brighter and plant flowers, so that someday, when the ships pass by their town, they will look at the bright, beautiful, fragrant town and say, “yes, there, is the village of Esteban.”

When the villagers set their vision on a higher purpose and start creating a conscious culture of values supported by a mission; when they change their orientation away from their smallness and dreariness and embrace possibility, recognizing multiple stakeholders and responding to the unavoidable contingencies of the external world, they enact a preparation for embodied citizenship that changes the community. These are also traits that describe a successfully managed organization, or maybe what we might call not Esteban’s village but “Ron Harris’s” village.