Bilingual Education: A Celebration of Personal and Linguistic Identity

In this week’s captivating blog, we embark on a fascinating journey through the vibrant world of bilingual education, as seen through the eyes of USF’s very own Kathy Siu. Her transformative internship with the McCarthy Center has provided us with an exclusive backstage pass to the thrilling rollercoaster of obstacles and soaring triumphs that come with the McCarthy experience!

Over the summer, I had the pleasure of being an Equity Intern for the USF McCarthy Center. As an Equity Intern, I participated in community walks, leadership training, and most important, the hands-on classroom experience. For eight weeks, I taught first grade at John Muir Elementary, a Title I school in San Francisco, where the majority of my students came from a low-income, Spanish-speaking background. My time spent with these students opened my eyes to the deep-rooted inequities in public education. In particular, the educational gap is a huge barrier for students, often making it nearly impossible for them to navigate the school system.

It is pre-existing knowledge that there are exacerbated inequities in the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, I believe that the approach to combat them has been overgeneralized. Solutions to combat inequity often hyperfocus on resource dumping and molding students into one cohesive identity. Money is targeted rather than creating well-thought-out, effective solutions that cater to the diverse backgrounds of students. From my perspective, real change comes from a radical shift in how we view inequity. A key area is the linguistic gap, which is frequently overlooked. In particular, there is a delayed response in educational policy to address the needs of bilingual students. Bilingual education is fundamental in serving the San Francisco student body, who possess unique linguistic skill sets and cultural heritage.

My partner, Eden Groum, and I explored this topic in our final project titled The Importance of Bilingual Education With Regard to the Changing Demographics of San Francisco. This presentation was extremely personal to me as for the past seven years I have been studying the Spanish language. I understand how difficult it is to learn a second language. The process can be overwhelmed by frustration, insecurity, and fear of making mistakes. In my classroom, many of my five-year-olds experienced this. On a daily basis, many of them would shut down emotionally from not understanding the instructions of worksheets in English. I found students intentionally avoid interactions with their English-speaking peers due to the language barrier. Furthermore, many of my students who recently immigrated from Latin America, talked about missing home and what was normal to them.

Despite these challenges, I truly believe that bilingualism is a vital skill if developed in a safe and caring environment. The ability to speak more than one language is an opportunity to create deep connections with people. I decided to pursue this topic in hopes of transforming bilingual education with consideration of the influx of immigrants in SF. However, our current public education system continues to be polluted with Eurocentric and bigoted policies. To illustrate, in 1998, California enacted Proposition 227, which resulted from the “English for Children campaign”. This legislation caused eighteen years of “English-only” instruction and a sharp decline in certified bilingual educators. Racist policies, such as Prop 227, still have an impact to this day and are a major threat to SF’s linguistic diversity. As educators, rather than shame students’ native tongues, we must fight to create classrooms that honor cultural heritage and linguistic diversity.

We can do this by changing our perspective to see language through a cultural lens. This approach is perfectly described in the book Borderlands, La Frontera, written by Gloria Anzaldúa, which explores the themes of migration, language, and identity. Anzaldúa quotes powerfully, “So if you want to really hurt me, talk badly about my language. Ethnic identity is twin skin to linguistic identity-I am my language (Anzaldúa, 58). Honoring the connection between ethnic identity and linguistic identity is essential to serve SF students. In fact, the city of SF is home to over one hundred and nine different languages. Additionally, one in three SF residents are an immigrant. On a state level, this equates to around 2,656,242 bilingual students in California. Language is how we express who we are as people, our emotions, hopes, and dreams. In light of this, to assimilate a student is to take away their mind, heart, and soul (Christensen, 8).

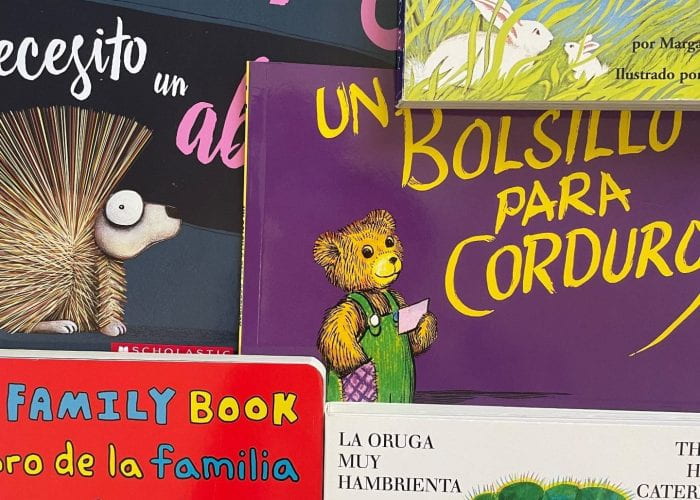

Ultimately, our theoretical framework to transform bilingual education focuses on seeing bilingualism as an asset. This begins with implementing a curriculum that is culturally relevant. For me, purchasing bilingual books was a way to encourage Spanish-speaking students to participate during circle time. Early in the program, Liam, a student who just immigrated from Peru, had significant behavioral challenges. Out of frustration, he would hit his non-Spanish-speaking peers and hated reading in class. However, I sought to understand him more and form a relationship rather than get discouraged. I found a Spanish translation of his favorite book, A Pocket for Corduroy (Un Bolsillo Para Corduroy). During a class break, we read the book together. To my surprise, the student who would hit others during circle time immediately became animated and narrated the entire story to me by memory. Every day after that, Liam developed a love for reading time and trusted me as his teacher. Throughout the program, we continued to read a variety of translations of classic books together (The Very Hungry Caterpillar, Are You My Mother?, The Runaway Bunny, etc.). The extra step I took to understand the life of my student and his needs made a complete difference. This change in approach, though appearing small, results in effective teaching for bilingual learners by leading with love and care.

Ultimately, in order to transform bilingual education there must be a complete change in the culture of the classroom. You can never teach a child a new language by ridiculing and erasing their first language. As teachers, we must continue to treat students with utmost respect and care, no matter the language barrier. In doing so, we will cultivate learning environments that embody rich linguistic and cultural diversity.