Resilience in SoMa

Recent Master of Arts in Urban and Public Affairs graduate and San Francisco native, Jeantelle Laberinto, focused her capstone thesis research on the Filipinx community in the San Francisco. Though centered on this community, it tells a wider story of an evolving city and how resilience can make the difference when facing urban change.

Know History, Know Self: Filipinx Resilience in the South of Market

I chose to enroll in the Urban and Public Affairs graduate program because the impacts of gentrification and displacement of low-income and working-class residents and communities of color were especially troubling to me amid this second tech boom. While I had many concerns about the dominance of tech and specialized sectors, the affordable housing crisis, and increasing inequality, my attention turned towards the communities being impacted. How were they responding? How were they fighting to stay in San Francisco?

These questions led me to intern at the South of Market Community Action Network (SOMCAN) last summer, where I was able to directly see what folks were doing on the ground. As the South of Market (SoMa) is ground zero for new development, as well as home to a large Filipinx population, I wanted to not only understand their anti-displacement strategies but stand in solidarity with them and support their efforts. One thing that was quickly made clear to me was that the current issues facing the community were part of a longer struggle against erasure. This is ultimately what led me to focus on this specific community for my capstone thesis.

The history of the Filipinx community in the SoMa is an important epoch in the Filipinx diaspora. As the history of the Filipinx diaspora has been shaped by United States capitalist hegemony and its expressions, specifically, within the sphere of urban planning, the Filipinx community in the SoMa has constantly faced threats of displacement and erasure. Using the theoretical frameworks of neoliberalism, hegemony, global cities, the “right to the city,” and the concepts of space, place, and resilience, my capstone, Know History, Know Self: Filipinx Resilience in the South of Market, investigates how the community has remained by articulating and developing counter-hegemonic resistance strategies that challenge the continuous pressure of capital and neoliberal hegemony. Through a historical analysis of the SoMa and interviews with community members, I found that the community has based its organizing and political action around a collective consciousness that draws on their history.

Historical Research and Interviews

I used two principal methods in my research. The most crucial, of course, was historical analysis. I traced and analyzed the history of the U.S.-Philippines colonial relationship and how struggles experienced by the Filipinx people were expressed at global, national, regional, and local scales. I analyzed city planning reports, census data, eviction data, housing trend reports, neighborhood area plans, and legislation and policy documents to gain a more comprehensive understanding of San Francisco’s priorities and how they have impacted this community. The second method included interviews with key members of the Filipinx community in the SoMa. This included directors of community organizations, legislative aides, and folks who have been directly involved in the community and have extensive knowledge of the community’s history.

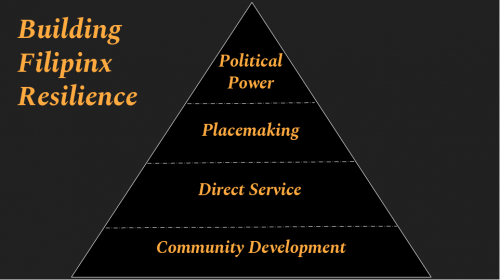

Through my research, I found that the history and experience of Filipinx immigrants is inextricably tied to the history of San Francisco, the greater Bay Area, California, and the U.S. as a whole. From World War II, to the formation of the United Farm Workers Movement, to the period of Urban Renewal, to the rise of San Francisco housing activism, Filipinxs have been involved and active in these points of history and in these struggles. By analyzing the history of the Filipinx community in the SoMa and looking at what the community has done to avoid erasure, I found that their resistance and resilience efforts could be grouped into four stages: 1) Community Development; 2) Direct Service; 3) Placemaking; and 4) Political Power.

My historical analysis led me to finding the most pivotal and crucial points in history that necessitated the creation of these strategies, tracing their evolution and the development of a collective consciousness that carried from the homeland to the diaspora, from colonization to the present.

These four stages are described in depth in my capstone, but they are periodized in such a way because each strategy builds off and is predicated on the existence of the infrastructure created by the previous strategy. The infrastructure created by community development, for example, was necessary in order to enable the emergence of direct service. Similarly, legislative policy and political power to protect the community could not be articulated without the creation of physical spaces (and places) that are significant to the Filipinx community. In my capstone, I also discuss the recent creation of the SOMA Pilipinas Filipino Cultural Heritage District, which I argue is the embodiment and culmination of all four strategies and serves as the strongest example of how the four strategies work to produce and articulate resilience, and most importantly, how the collective consciousness built throughout the Filipinx community’s struggles and triumphs actively informs the community’s social and political formations.

From building a community of Filipinx immigrants through community development and providing various social services to the community, to building businesses and education centers and asserting place through transformation of the SoMa’s built environment, to now, with community activists taking part in politics and legislation, the Filipinx community has constructed an alternative hegemony against the pressures of capital and neoliberalism that have continually threatened to displace and erase them.

In my conclusion, I argue that the community began to understand that they themselves must learn the language of urban planning, land use, and policy to challenge market forces that were accelerating their erasure. The community itself had to understand and utilize policy and legislation to equalize the power dynamics between the community, developers, urban planners, and elected officials. Essentially, the Filipinx community began to understand that if they learned to speak the language of the powerful, they could no longer be ignored. It is the hope that the framework described in this research can be used to study similarly marginalized communities. It can also form the basis of a more equitable form of community-involved planning instead of a neoliberal, market-driven urban planning paradigm.