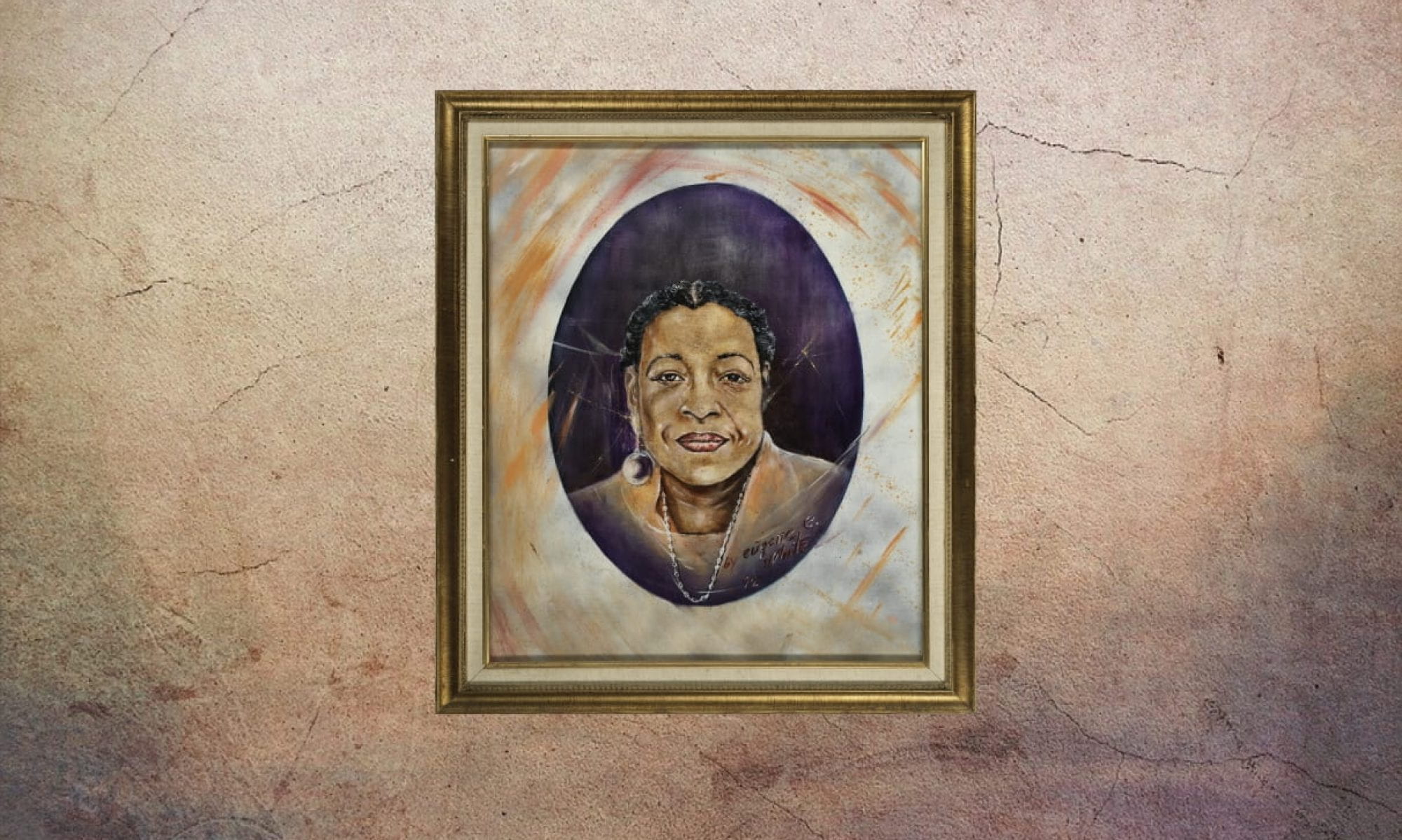

Thomatra Scott, a youth program coordinator for the Economic Opportunity Council’s (EOC) Multiservice Center, broke the status quo to elicit a change within his community. He was an advocate for kids in education, health, housing, employment, human rights, prison reform and cultural/ethnic issues.

Thomatra Scott was unable to pursue his education after high school and became a taxi driver while beginning his work in the Western Addition. In 1969, at the height of the Black Power era, Scott joined the Pan–African People’s Organization (PAPO) where he promoted Kwanza and the seven principles of the holiday to black neighborhoods. Rapid expansion of community activities were administered through the NAACP and the Council for Civic Unity, which led to the growth of youth affiliated activities to promote safe and healthy living. Scott began organizing a drum and bugle corps through the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) which brought students together from all backgrounds to create music on their own terms without outside hindrance.

Scott was a husband and father to one daughter and was also the honorary parent to hundreds in the Western Addition. His focus was centered on the San Francisco Postal Street Academy, also known as Polytechnic High School. According to Susan Almazol of the San Francisco Chronicle, students attending this school were dropouts, arrested juveniles, and tended to have “delinquent tendencies.” Scott’s dedication and enthusiasm for education manifested into a tough, non-compromising attitude towards both his students and government agencies. He felt that the youth should be involved in the decisions being made about their education. Scott’s deep sincerity and commitment to the well-being of the Western Addition youth was evident in his work leading the State Legislative Symposium on Children and Youth Services, while also participating as an active board member in the Westside Community Mental Health Center. Scott recognized that the growing number of adolescent teenagers in the street was a direct result of the poor educational services provided by the city. In response to this growing issue, he fought against the government’s closure of the San Francisco Postal Street Academy by counseling and encouraging boys being released from detention centers to “spell out the hard truths of the results of their neglect from their ghetto childhood” (Hamilton and Dungan). The introduction of remedial reading courses was created for the youth reentering society in an effort to prove the program’s legitimacy to the government.

Thomatra Scott frequently told his students, “Getting out with a degree to make a buck isn’t enough. You have a commitment to the youngsters you left behind who aren’t in school” (Hamilton and Dungan). Scott emphasized the importance of giving back to the community and fostered the personal growth of its members.

In 1977, two years after his fight with the government, Scott was honored as a longtime youth worker. He received a grant to go toward “creating youth foundations in their names, assisting in developing youth projects and awarding scholarships to deserving disadvantaged young people” (Hamilton and Dungan). The grant contributed towards Scott’s efforts in growing Young Adults, Inc., and expanding their mission to reach youth beyond the San Francisco area.

In 1983, Scott became the first Western Addition candidate to win an award from the San Francisco Foundation. Activists were honored for work in education and youth development. Scott was labeled as a “motivator and activist” for children, according to the San Francisco Examiner. The attitude of aggression towards Thomatra Scott and his compatriots began to dissipate as societal norms shifted on a global scale and racial prejudice became less accepted. Acknowledging his city-wide efforts validates the previously underrepresented youth.

Until his death in 2000, Thomatra Scott was a prominent figure in the Western Addition because of his extensive work in promoting the importance of education and for his efforts in keeping adolescent teens out of correctional facilities. Scott’s legacy will live on through Young Adults, Inc., and the dynamic tutoring, counseling, and drug prevention that became a model on a national level.

— Annelise Suleiman and Zoe Foster

Works Cited

“A Clash Over New Poly High Principal.” SF Chronicle. 2 Sep 1970, A 7.

Almazol, Susan. “Area Youth Units Pushed.” SF Chronicle. 18 Jun 1969.

“Awards Honor the Distinguished Ten.” SF Chronicle. 30 Mar 1975.

Hamilton, Mildred and Dungan, Eloise. “Activist for Youth.” SF Chronicle. 16 Mar 1975.

“Poly High States Demands to Board.” SF Chronicle. 6 Aug 1969.

Sixty-Two Heroes and Pioneers of the Western Addition. African American Cultural and Historical Society. 2010.

“Western Addition Achievers Win First S.F. Foundation Awards.” SF Examiner. 22 Apr 1983, B14.

Wong, Ken. “Crisis at School for Dropouts.” SF Examiner. 17 May 1972, A 12.