Education is a right that should be given to all, not a privilege only for a select few. This was the ideal that Dr. William L. Cobb upheld throughout his career in education. Cobb was one of the first African American teachers in San Francisco, and the first African American principal and assistant superintendent of human relations. He was a pillar for educational evolution through his tireless work to desegregate San Francisco’s Unified School District.

In 1910, William L. Cobb was born in Jonesboro, Arkansas, to LeAnn and Harold Cobb. After moving around for a few years, Cobb attained his high school degree and attended Texas College, earning a bachelor’s degree in Social Studies in 1935. In 1940, fewer than 10 percent of 25 year old people of color had completed a four-year high school education, so for Cobb to not only have completed high school, but attained a bachelor’s degree in Social Studies from Texas College was an outstanding accomplishment. Additionally, he was one of the first black men to earn a master’s degree in education and an Ed.D. in educational administration at the University of California. Upon entering his twenties, Cobb immediately began working to change the imbalanced and segregated educational system as a teaching principal at North Chapel High School from 1935–41 and Hawkins High School from 1941–43 in Texas.

After making strides in education as a teaching principal, Cobb served in the US Navy from 1943 to 1946. After the war, he moved to San Francisco and became the first African American principal in the San Francisco Unified School District. Cobb served at Emerson elementary school from 1947–1963 until he was appointed as the assistant superintendent of human relations.

When asked to describe his emotions upon receiving this position, which allowed him to create more avenues for racial integration, he explained that he “doesn’t believe in miracles.” As a man of action and initiative, he knew “that intolerances can be broken through education.”

Upon entering this position, the community, fellow educators, and prospective students all welcomed Cobb with open arms. Dr. William McKinley Thomas, a highly regarded member of the San Francisco Housing Authority, said that “the best way for a community to help itself is to practice the democratic ideals wherein rewards are waiting for those willing to work for them through self-improvement. This is another step in the advancement of the Negro community.”

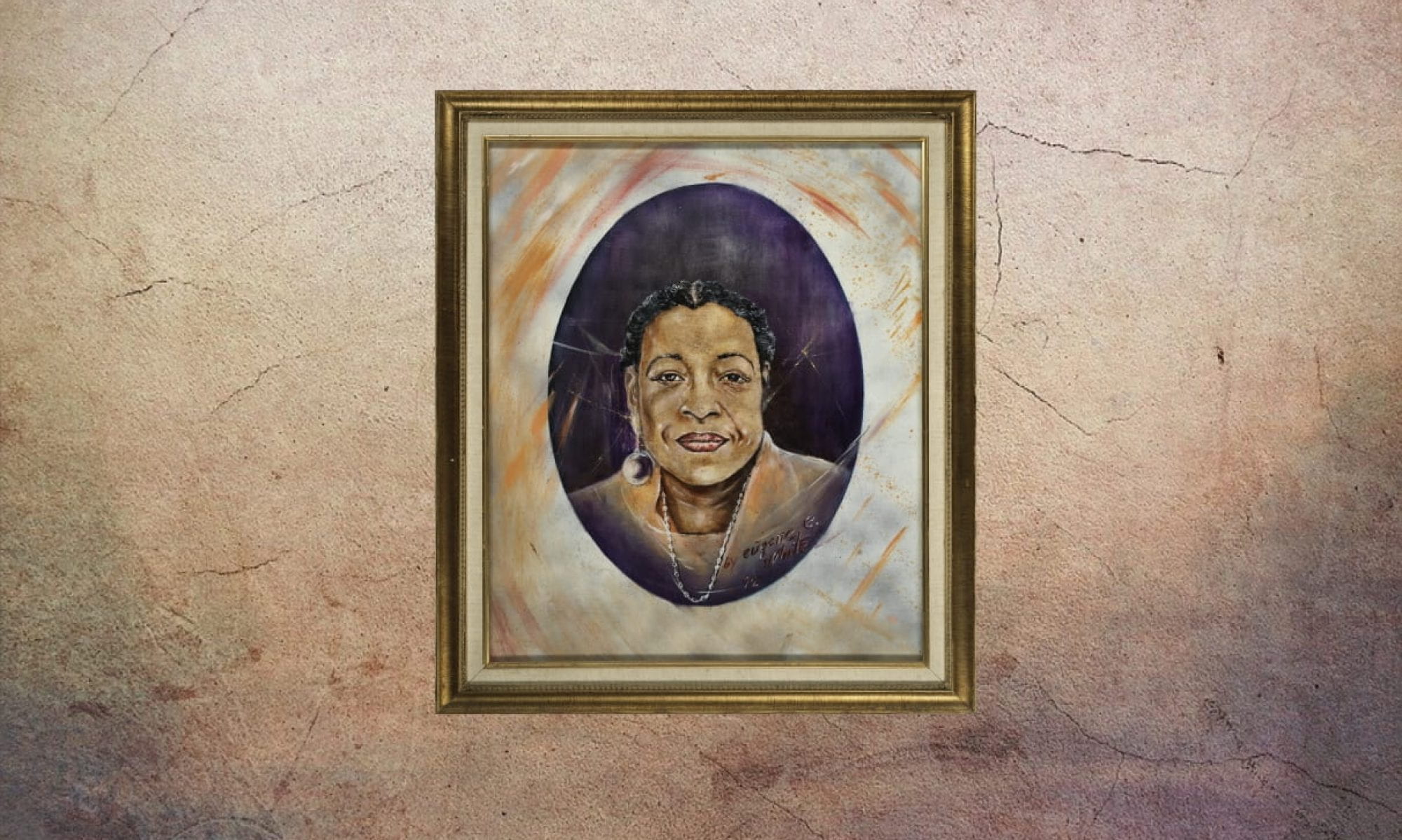

Dr. William Cobb was the first African American teacher and principal in the San Francisco Unified School District.

In the late 1960s, however, the community grew impatient with integration initiatives. Claims had been made against Cobb and the Board of Education stating that they have held an evasive attitude towards specific initiatives in integrating the schools. In April 1964, a picketing of the School Board hosted by the NAACP and CORE (Congress of Racial Equality), roused the community to seek answers for unanswered questions. Reginald Major of the NAACP claimed, “the board has been evasive on several issues concerning race, and we are convinced that problems are being created faster than they are being solved.” Cobb emphasized that “none of the proposed redistricting involves transporting students by bus solely for the purpose of bettering racial balances.”

In the article “Top Secret Plans on School Busing,” published in 1969 by the San Francisco Examiner, Cobb and the rest of the Board of Education concocted a “secret and confidential” plan that would utilize the bus system to integrate 20 elementary schools holding tens of thousands of students (Wood). Once the plan was set in motion and approved in January of 1969, Cobb insisted that no publicity be given on this report. After passing this initiative, Cobb promoted the passing of more bills to continuously aid the full and equal integration of K–12 institutions.

In addition to becoming the first African American principal and assistant superintendent chair, Cobb was also a pillar of the community and a celebrated social activist. Cobb held a Board of Director position in the Family Children’s Agency and served on the Board of Governors of the YMCA, both of which promoted the pursuit of education and equality within African American communities.

Cobb died in November of 1976 at the age of 66. He was survived by his wife Irma, a fellow educator in the San Francisco Unified School District and Oakland School District, and his son Dr. William Cobb Jr., and his three grandchildren. Because of Cobb’s hard work throughout the years, Emerson Elementary School changed its name to William Cobb Elementary School to honor his legacy.

— Ya’qub Elmi and Chaniece Jefferson

Works Cited

“120 Years of American Education: A Statistical Portrait.” Jan 1993.

Center for Education Statistics. “Appointment Lauded: Board Praised for Naming Negro to School Past.” SF Examiner. 21 Aug 1947.

“Cobb Tells Surprise at Selection by Cash.” SF Examiner. 22 Aug 1947.

Edises, Pele. “Something New Comes to Emerson.” SF Examiner. 4 Sep 1947.

Gilmore, Lance. “NAACP Shifting Aim on S.F. School Targets.” SF Examiner. 30 Jul 1968.

Moskowitz, Ronald. “Two Groups to Picket School Board.” SF Examiner. 7 Apr 1964.

“School Race Issue Revived.” SF Examiner. 17 Jun 1984.

Wood, Jim. “Top Secret Plans on School Busing.” SF Examiner. 30 Jan 1969.