Biodiversity in the City

Recently, I’ve been hearing a lot of people say how they’re “not big on nature” or don’t find themselves enjoying nature’s bounty as much as they’d like to. There’s this idea that nature is raw and untouched land far away from any human activity, and I believe that a lot of us might feel disconnected from the environment because of these perspectives. But I’m going to let you in on a little secret: nature exists all around us! I’m nature and you’re nature. Our homes and classrooms and grocery stores and parks are all nature – even if they’re a part of the built environment and didn’t grow from the ground like a little flower. So to me, it doesn’t make sense why people feel so removed from the natural world when, in fact, it’s all around us.

Our misinformed views of nature have ripple effects on how humans interact with the environment. For one, restrictive views of nature affect what land and life we classify as worthy of protection or conservation. Let me elaborate. When I say “nature,” what do you think of? Perhaps you envision a landscape like Yosemite in the Sierra Nevadas with dramatic rocky cliffs, verdant valleys, icy blue rivers, and ridiculously tall redwood trees. The beauty in this landscape is undeniable, and when John Muir laid eyes on what would one day become Yosemite National Park, he created an entire conservationist movement to protect this land from human-induced harm to preserve its inherent beauty. Now these protected lands, which are basically considered the supermodels of environments, define how people view nature, acting as imaginative constraints in the process.

Do you see what’s wrong here? In creating the national parks and separating pockets of the environment from human usage, society decides what elite bits of the environment are most beautiful or sacred and deserve to be isolated from the commons. This stems from our misunderstandings of what is ‘natural’ and what are valuable traits in an environment that make it worth protecting. For example, guiding the transcendentalists and the creators of the national parks were beauty standards for nature largely influenced by Christianity. Renowned ethicists, including Immanuel Kant, viewed sublime landscapes as “those rare places on Earth where one had more chance than elsewhere to glimpse the face of God” (Cronon 10). In looking for the presence of God and the ‘sublimeness’ of grand landscapes, the ecological value of land was neglected for biblical aesthetics. The first national parks, including Yellowstone, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, and Zion, all fit this narrative. Figures like Muir recognized such a resounding beauty and god-like presence in these environments that merited protection from the threat of humanity. Less sublime environments were decided not worthy of such protection. As Cronon illustrates, the first swamp, Everglades National Park, would not be honored until the 1940s, and grasslands failed to receive the attention they deserve in terms of national park classification (Cronon 10).

Yosemite Valley via Pexels.com

The application of beauty standards to the environment to mark its value is one factor that influences our western understanding of nature. Yet another would be how humans determine what is natural by evaluating their own involvement with the environment. The conceptualization of wilderness “embodies a dualistic vision in which the human is entirely outside the natural,” meaning that as humans, we are inherently unnatural so the most natural of environments are ones that are untouched by humankind – which of course denies the validity or existence of Indigenous peoples (Cronon 17).

So now we’ve laid a solid groundwork of why our views of nature seem to be deeply problematic. Cool. Where does that leave us now in an urbanized, covered-in-concrete San Francisco?

First, we can realize that if humans are a part of nature, then everything they construct and everywhere humans live are nature too. But expanding our views of nature also means expanding our consideration for the health and wellbeing of our ecosystems. Once we’re able to recognize the value in the natural environments that we live in, we should feel a sense of empowerment to take care of them and to steward our found environment in a way that is congruent to how it would function without human intervention. Especially in the context of San Francisco, the way that we construct our cities and live our lives does not need to afflict the ecology that’s thrived in this place for thousands of generations.

This is where the idea of biodiversity in the city comes to play. According to the San Francisco Department of the Environment, despite being 95% developed, San Francisco contains “dozens of natural ecological communities, harboring an astounding diversity of birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians, rare and endangered species, and over 500 local native plants” (sfenvironment.com). But the San Francisco bioregion is under major threat due to urban civilization that has dramatically altered the environment and habitat of local flora and fauna.

San Francisco’s Environment via matadornetwork.com

A new era of environmental stewardship is upon us, and thanks to our reimagined relationship with the environment, we can begin to think of San Francisco as a place where people can thrive in conjunction with the rest of the natural world.

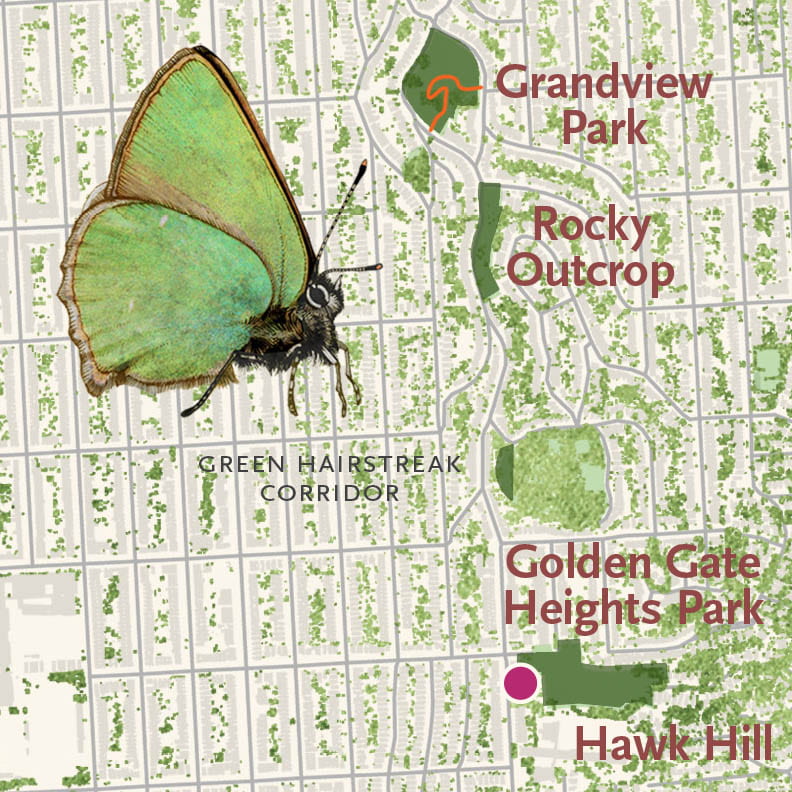

An important initiative related to biodiversity in San Francisco that comes to mind and provides an excellent example of what a more biodiverse and environmentally inclusive city could look like is the Green Connections Network. The Green Connections Network is a map of 24 routes, totalling 115 miles of streets, that are designed to connect both people and wildlife species to parks and open spaces. These habitat corridors are designed for a variety of “key species” to facilitate their travel and migration through the dense and sometimes dangerous city landscape. For example, “green connections routes 22 and 23 are dedicated to the white-crowned sparrows and coyotes, where more shrub and grass habitats could be planted” (Keenehan) to meet their needs. Green connections also increase plant diversity and make access to pedestrians more pleasant and accessible in the process. What does this case study show us? The needs of people and the environment are not mutually exclusive. Instead they are deeply connected. In serving one group, it’s possible to benefit the other community simultaneously and increase ecological health throughout the process.

The Green Hairstreak Corridor via Nature in the City.

When we open our minds to what nature is and where it exists, our capacity to live in a more ecologically-inclusive community (even if it is an urban environment) becomes so much more feasible. I encourage you to embrace the biodiversity that exists around you and learn more about how you can aid in the wellbeing of your brother and sister creatures on this earth!

Works Cited

Cronon, William. “The Trouble with Wilderness or Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” Uncommon Ground: Toward Reinventing Nature. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1995.

Keenehan, Sean. “A Wild Plan for San Francisco”. WTTW.com. https://interactive.wttw.com/urbannature/wild-plan-san-francisco#!/

San Francisco Environment Department. https://sfenvironment.org/biodiversity#:~:text=Despite%20being%2095%25%20developed%2C%20our,is%20also%20under%20serious%20threat.