The Slow Water Movement and Resisting the Human Desire to Control Nature

The Western relationship between humans and nature is dominated, or should I say polluted, by a human/nature dualism. Dualism is the division of something conceptually into two opposing or contrasting aspects, and in this case the thing being divided is life on Earth. Dualisms generally imply hierarchy, with one dominating or controlling the other. This can be seen in many aspects of the Western human relationship with the natural world, from turning biodiverse grasslands into mono-crop agricultural plots, flattening forests to create parking lots, and extracting our prehistoric ancestors’ remains to be burned as fossil fuels. Many humans, specifically very privileged humans, consider needs and wants to be more important than nature’s right to exist.

Today, the human-nature relationship that I will be examining is that between humans and natural water systems. Humans have manipulated Earth’s water systems in a myriad of ways, turning them into something that is fast moving and global, when this is in fact the opposite of most water systems’ natural movement. Water naturally tends to stall on flat land, forming wetlands and seeping deep underground. This is useful as it creates habitat space for animals and helps purify water for human use. Unfortunately, humans are inclined to use flat land for development, which has led to the destruction of 87% of the world’s wetlands. Loss of this wetland not only means significant habitat loss for amphibians but also puts more stress on remaining wetlands. Wetlands play a huge role in filtering pollutants from surface water, which means that having a fewer quantity of wetlands will increase the pollution in remaining wetlands. Streams have also taken a huge hit as urban areas continue to sprawl, with many streams being “undergrounded” which means that they are funneled into a pipe and buried under concrete. This not only eliminates their use as a resource for wildlife but also decreases the health of hyporheic zones, which are underground wetlands extending many meters beyond creeks.

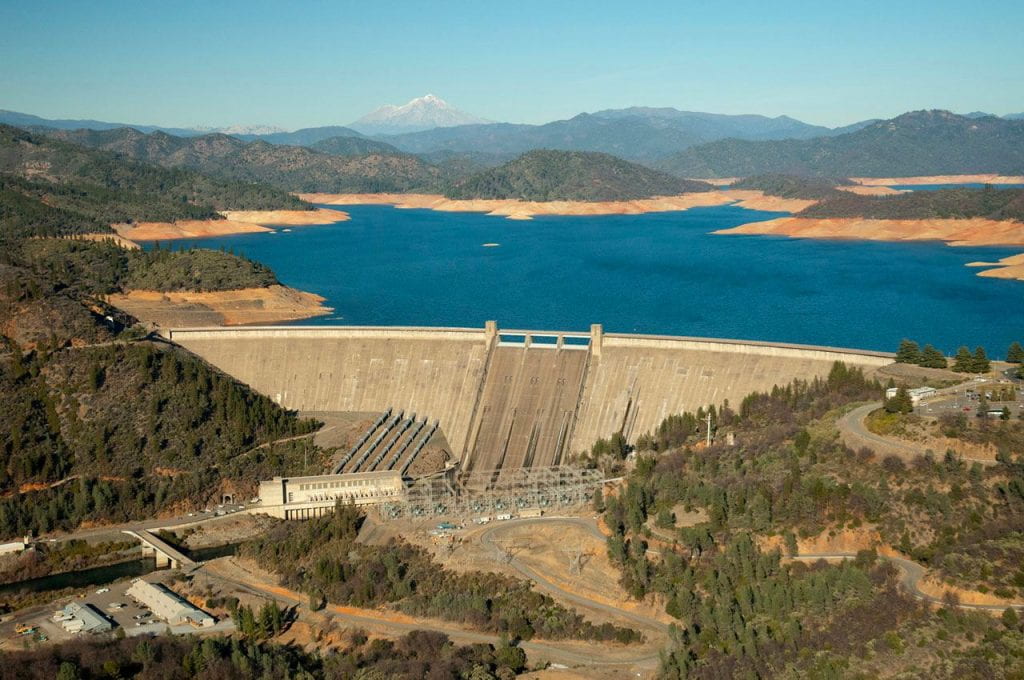

Shasta reservoir

Source: Public Policy Institute of California

In addition to wetland destruction for industrial development purposes, humans have also altered our water systems through the process of damming and the creation of reservoirs. This is usually for the purpose of flood reduction or maintaining a stable water supply throughout the year for human agricultural, commercial, and residential use. Though damming has a number of negative ecological impacts including increased risk of dead zones (areas where the process of eutrophication has resulted in dissolved oxygen levels so low that it is impossible for living organisms to survive) and habitat reduction, damming is also a human environmental justice issue. While dams and other interventions on big rivers have brought more clean water to 20% of people over a 20 year period, this same water has been taken from 24% of people. When you dam a river or create a reservoir, you are never simply supplying a community with clean water; you are always taking it from somewhere else, most often a less privileged community.

Coastal wetlands in the Bayland Nature Preserve

Source: California Water Blog

The primary solution to this problem has been to slow down our water cycle, with petitioners of this solution starting the “Slow Water” movement. But what is this? The slow water movement was inspired by the slow food movement, which started in Italy in opposition to fast food. The slow water movement is based in shifting from a mindset of control to a mindset of respect. The slow water movement is very local and intends to work with local cultures and ecosystems rather than try to control them. Slow water projects tend to be very small-scale and nature-based, including things like restoration of grasslands to absorb stormwater runoff, daylighting streams that have previously been undergrounded in order to create habitat for birds and insects, and reforesting the riparian zones surrounding creeks and streams. These are all examples of nature-based climate change mitigation projects, which focus on improving ecosystems’ ability to sequester carbon and filter pollutants and increasing Earths’ ability to heal itself.

Although the many global changes we have made to our water systems are irreversible, the power of small-scale and local restoration projects should not be underestimated. San Francisco’s Presidio Trust and National Parks Association have been working on restoration projects in the Presidio for the past 20 years, with the largest project being the Restoration of Quartermaster Reach Marsh. Quartermaster Reach Marsh is located near Crissy Field on the northern shore of the Presidio and is named after the U.S Army’s Quartermaster Corps which operated in the area when the Presidio was used as a military base. This restoration project brought 850 feet of stream out from underground and connected the Tennessee Hollow Watershed with the San Francisco Bay. The union of these two fresh and saltwater sources created a brackish marshland, which is ideal for many of the native species that were planted. The project focused on using construction materials that support the growth of Olympic Oyster larvae which used to be extremely common in the San Francisco Bay before overharvesting by settlers. Native plants like fleshy jaumea, sea milkwort, and alkali bulrush were also planted in the marshland and have positive impacts on native animals.

Quartermaster Reach March

Source: National Parks Service

Since the restoration project’s commencement in the spring of 2020, the area has seen a significant increase in bird activity as migratory birds use the marsh as a stop-over point in their journey. This has not only increased the biodiversity of the park but is also pleasing to many birdwatchers who love to enjoy wildlife in the city! Since the project is relatively new, there is little information about specific impacts of the marsh on the larger Presidio ecosystem. The Presidio Trust is continually monitoring environmental indicators like animal presence and air quality to gauge the effectiveness of restoration projects. Quartermaster Reach Marsh is by no means the end of restoration work in the Presidio, as Presidio Trust and the National Parks Conservancy work tirelessly to increase the health of our urban ecology, working with nature rather than against it.