by Colter Ruland —

Love him or loathe him, you’ve probably at least heard of Roberto Bolaño. The Chilean author’s work exploded in the 2000s, managing to overcome even American readers’ supposed indifference toward works in translation. With his last complete novel, the sprawling 2666—published in 2004, the year after his death—Bolaño secured his place alongside Jorge Luis Borges and Gabriel García Márquez as one of the great Latin American writers of the last century. Fast forward a few years, to 2014: as the Bolaño craze starts to fade away, out comes A Little Lumpen Novelita, a skinny translation that reminds us Bolaño is still very much a part of the literary scene.

Love him or loathe him, you’ve probably at least heard of Roberto Bolaño. The Chilean author’s work exploded in the 2000s, managing to overcome even American readers’ supposed indifference toward works in translation. With his last complete novel, the sprawling 2666—published in 2004, the year after his death—Bolaño secured his place alongside Jorge Luis Borges and Gabriel García Márquez as one of the great Latin American writers of the last century. Fast forward a few years, to 2014: as the Bolaño craze starts to fade away, out comes A Little Lumpen Novelita, a skinny translation that reminds us Bolaño is still very much a part of the literary scene.

Written as Bolaño was working on 2666,Lumpen has been overshadowed by his longer, more sprawling fiction. Lumpen is much more singularly focused than any of those works, following only one main character through a mostly plotless series of events. Orphaned in Rome, Bianca and her brother find jobs at a hair salon and gym, respectively, in order to sustain themselves. Her brother brings home X-rated movies, which they watch with the same absentmindedness other children might give to cartoons. Soon Bianca’s brother also brings home a Libyan and Bolognan, both of whom remain nameless and descriptionless. They move into the siblings’ tiny apartment. Bianca starts to sleep with the Libyan and Bolognan, without passion: she leaves the lights off to conceal the identity of which of the two she’s sleeping with. Eventually the brother and the two gangster-types convince Bianca (coerce? encourage? it isn’t exactly clear) into seducing a champion bodybuilder for a fortune that may or may not be held in a secret safe in his dilapidated Italian villa.

Pretty Bolañoesque, right? It fits right into the “Bolañoverse”, a dark fictional realm of twentieth-century decay replete with poet-gangsters, psychological suspense, horror tropes, dark smoky atmospheres, heightened sexuality, and lots and lots of murder. Yet the restraint in Lumpen is astonishing, making it both the most and least Bolañoesque novel I’ve yet to read.

The situation of Lumpen is complicated by its past-tense narrative, indicating that Bianca, narrating from some point in the future, is still grappling with her sexual exploits with the Libyan, Bolognan, and the champion bodybuilder. Bianca admits, “for a few days I lived on tiptoe,” and the novella likewise tiptoes around being conclusive. This is typical Bolaño: he dangles potential conflicts before us like carrots on sticks, only to jostle them away before we can grab them. Nothing is resolved with the Libyan or Bolognan, for instance. They remain emotionless, even when Bianca starts making up excuses to prolong her seduction plot in the villa, thereby hindering their scheme. You’d think this would lead to some kind of violent outburst on the part of the two men, but nothing really comes to a head. This is not how fictional conflicts traditionally resolve themselves; there is no cathartic or confrontational climax.

Nothing is clear in this story. While that fact may frustrate some readers, it also makes for an enthralling, atmospheric, and dreadful reading experience—dreadful in the sense that something is always lurking behind the next page, ready to snap. In Bianca’s strange first encounter with the champion bodybuilder, she is lured inside and directed through his unlit house by a voice over the intercom. The villa is similarly disjointed: one room contains all the furniture of the adjacent rooms piled in one large heap. This is one of the great joys of Bolaño. He allows your mind to wander, to imagine what terrible things are going on beneath the surface of characters’ motivations and (usually wrong) decisions. It’s a sort of potential energy in the reading experience.

Sometimes the tension does snap in Bolaño’s works; in 2666, this happens in one monumental section, “The Part about the Crimes”. But in Lumpen, Bolaño seems only interested in stretching the tension as unbearably taut as he can, without breaking it. This is how he can pack such a huge punch in so few pages. The opening line—”Now I’m a mother and a married woman, but not long ago I led a life of crime”—immediately raises all sorts of questions. What life? What crime? But nothing’s ever explicitly answered, and Bianca’s “life of crime” don’t seem to amount to anything as criminal as the Libyan or Bolognan. This withholding of information is sinister yet purposeful, permeating every sentence, constantly building but never concluding, keeping you guessing and coming back for more, as if lured in by the same disembodied voice as in Bianco’s first encounter with the champion builder.

The champion bodybuilder is himself a hulking, bald presence of apathetic, lazy evil. By lazy, I mean a slow, deliberate, quiet kind of evil, an evil that springs from boredom, old age, and time. The rooms of his villa are empty. He is blind. His body is no longer what it was literally prized to be. He has evaporated into a list exes: ex-bodybuilder, ex-champion, ex-movie star. His real name is Giovanni Dellacroce; his stage name is Franco Bruno; his public name is Mr. Universe; his acting name is Maciste. He embodies the total sum of exhaustion—and yet Bianca still looks over her shoulder whenever she’s in the villa (as does the reader).

Bianca’s tone in recalling her seduction of Maciste subtly transitions from calculation to pity to awakening. Whereas Bianca sleeps with the Libyan and Bolognan as a way to see the “negative of romantic situations […] the negative of passionate moments […] the negative of a whole life,” it is with Maciste that Bianca tries to regain something that has been, or might become, lost. And vice versa: for Maciste, sleeping with Bianca is a way to regain his past. For Bianca, visiting Maciste is a way “to think about the future.”

Or is it? Bianca regularly undercuts her own assumptions. In the above case, she immediately follows up her thought by wondering whether “you can call it thinking (and if you can call it a future).” She seems on edge about what it means to be having sex with someone who has essentially tapped out of life: Is it an awakening? If so, an awakening to what? Maybe she is trying to escape her orphanhood, or from the two men living in her apartment, but what is she escaping to? Bianca reflects halfway through the novella: “I didn’t like my life. The nights were still crystal clear, but I had become less of an orphan and I was moving into an even more precarious realm where I would soon lead a life of crime.” She is simultaneously thinking about the future, and utterly failing to imagine it. And again, what crimes are she in fact committing? If anything, Bianca appears to be self-policing by reminding herself constantly that her past is bad and the future is … well, not bright, but at least better. Whatever firm ground you think you have regarding Bianca’s motives is quickly tugged out from under your feet.

In Lumpen, Bolaño hopes to show us that plots and subplots do not necessarily need to be connected or wrapped up. To do so would be a Dickensian trick. Instead Bolaño keeps our attention with Bianca’s strong, complicated voice, and with the increasingly weird situations she find herself in. The atmosphere and prose in Lumpen shines from underneath its own dark cover. Lumpen‘s refusal to resolve is also a healthy antidote to the tendency in mainstream American crime fiction to wrap things up tidily. Contrast Bolaño to Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, which is so controlled with respect to plot and character psychology that it becomes both predictable and preposterous (yes, even with its ridiculous “twist”). Or Lauren Beukes’s Broken Monsters, which tries to mask its predictability by divvying its narratives into several points of view that overlap in unbelievable and ultimately formulaic ways. While these American novels deal with the same dark subject matter as Bolaño—various permutations of crime, violence, and sex—they exist on the opposite end of a spectrum from the Chilean, emphasizing plot, where Bolaño focuses on developing atmosphere and a documentary-like sense of inconclusive realism. It’s like we’ve fallen right into the middle of Bianca’s “life of crime” rather than into someone’s crafted narrative. If anything, Bolaño is anti-twist.

I’ve described Lumpen‘s foreboding atmosphere as lazy, but I don’t mean that it is carelessly constructed; rather, I just mean that the evil is like that of a sleeping troll waiting to be awakened, its dreadful snores signaling disaster but never awakening to it. The atmosphere is eerie and dingy in the best possible way, as in sentences like: “[Maciste] said this in a voice in which there wasn’t a hint of ailing, a voice that boomed in the darkness as if, the darkness, was a muzzle, and he was straining at it furiously, itching to come out on the porch and gobble up my brother’s friends[…]” You get the sense that Bianca is dealing with supernatural forces beyond her control, forces that never quite reveal themselves.

Despite its brevity, Lumpen makes for a poor introduction to Bolaño; it’s merely a glimpse into a much larger world. I wonder if Lumpen would be accessible to anyone who has not already fallen head-over-heels with Bolaño. Lumpen is indeed “lumpen” in how underdeveloped it is compared to the likes of The Savage Detectives and 2666. However, the novella also teeters with possibilities, the same way good horror teases us with glimpses rather than full-blown looks at that which terrifies.

If you’re looking for a novel with conclusions, keep looking. In the end, Bianca discovers Maciste has no safe. She finds herself trapped between the man she is seducing and the friends and family who want her to steal a nonexistent stash she knows does not exist. She stays anyway. This is perhaps Lumpen‘s greatest horror, this obscure non-ending, this lack of epiphany. Then again, I didn’t read Lumpen for traditional epiphanies. One rarely does with Bolaño.

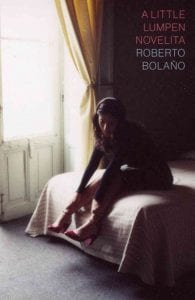

A Little Lumpen Novelita

Roberto Bolaño, translated by Natasha Wimmer

New Directions Publishing Company, 2014

ISBN 9780811223355

Colter Ruland is currently pursuing his MFA at the University of San Francisco after moving from the no-man’s-land that is Arizona. His short fiction has appeared in Persona Magazine and Danse Macabre. He is working on his first novel.

Colter Ruland is currently pursuing his MFA at the University of San Francisco after moving from the no-man’s-land that is Arizona. His short fiction has appeared in Persona Magazine and Danse Macabre. He is working on his first novel.