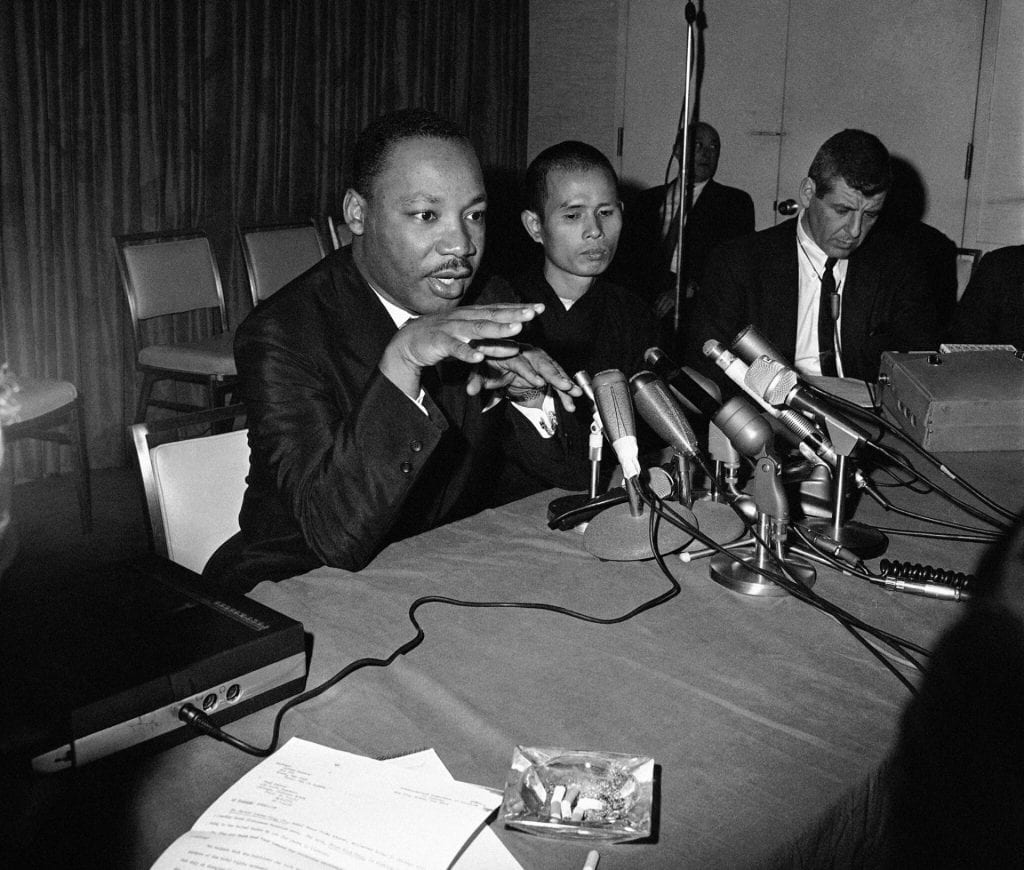

Martin Luther King Jr. & Thích Nhất Hạnh, Chicago 31-5-1966; Edward Kitch | Credit: AP; Creative Commons

Prior to June 1965, Dr. King had occasionally expressed concern about the war in Vietnam, but he had done so publicly only in a tentative and extremely cautious manner. King was acutely aware of the risk that direct criticism of President Lyndon Johnson on his Vietnam policy risked jeopardizing the strong and critically important relationship he had developed with President Johnson in support of his civil rights efforts. However, various factors began to shift Dr. King’s understanding of the vast human suffering perpetrated in Vietnam and, as a result, his opposition to the war slowly began to intensify, eventually leading to an unequivocal moral condemnation of U.S. war policy, and a fundamental break in his relationship with Johnson.

Thich Nhat Hanh, an immensely courageous Buddhist monk from Vietnam, played an important role in educating Dr. King about the reality of the war from a Vietnamese perspective and inspiring King’s transformation into a national leader in the anti-war movement.

In early June 1965 Martin Luther King, Jr. received a long letter from Thich Nhat Hanh (affectionately known as Thay) entitled “In Search of the Enemy of Man.” Two years earlier, the Vietnamese monk Thich Quang Duc sat down in the lotus position; a colleague poured gasoline over his head, and Quang Duc lit a match, burning himself to death to protest persecution of Buddhists by the South Vietnamese government of Ngo Dinh Diem. Over the subsequent months, five more monks set fire to themselves. In this context, Thay reached out to Dr. King.

“I believe with all my heart that the monks who burned themselves did not aim at the death of the oppressors but only at a change in their policy,” Thay wrote. “Their enemies are not man. They are intolerance, fanaticism, dictatorship, cupidity, hatred and discrimination which lie within the heart of man.”

Thay understood that Dr. King had long been preaching the same message. His enemies were not men but injustice, racism, prejudice, hatred, poverty and militarism.

[T]he nonviolent resister seeks to change the opponent, to redeem him. He does not seek to defeat him or to humiliate him. And this is very important, that the end is never merely to protest but the end is reconciliation… And so the aim must always be to defeat injustice and not to defeat the persons who are involved in it.” (Martin Luther King, Jr, “Non-Aggression Procedures to Interracial Harmony,” Address Delivered at the American Baptist Assembly, 23 July 1956.)

Thay appealed to Dr. King to understand parallels between the nonviolent struggle of the Vietnamese Buddhists and the black freedom movement for human rights in the Jim Crow south. As Dr. King had preached that “[w]e must continue to believe that the most ardent segregationist can be transformed into the most constructive integrationist…,” (“Facing the Challenge of a New Age,” Address Delivered at the First Annual Institute on Nonviolence and Social Change, 3 December 1956), so Thay wrote to King: “I also believe with all my being that the struggle for equality and freedom you lead in Birmingham, Alabama… is not aimed at the whites but only at intolerance, hatred and discrimination. These are real enemies of man — not man himself.”

Above all, Thay urged Dr. King to speak out against the war. “I am sure that since you have been engaged in one of the hardest struggles for equality and human rights, you are among those who understand fully, and who share with all their hearts, the indescribable suffering of the Vietnamese people. The world’s greatest humanists would not remain silent. You yourself cannot remain silent…. You cannot be silent since you have already been in action and you are in action because, in you, God is in action, too…”

Here Nhat Hanh echoed the call of Rabbi Joachim Prinz, whose speech at the 1963 March on Washington had immediately preceded Dr. King:

“When I was the rabbi of the Jewish community in Berlin under the Hitler regime, I learned many things. The most important thing that I learned under those tragic circumstances was that bigotry and hatred are not the most urgent problem. The most urgent, the most disgraceful, the most shameful and the most tragic problem is silence. A great people which had created a great civilization had become a nation of silent onlookers. They remained silent in the face of hate, in the face of brutality and in the face of mass murder. America must not become a nation of onlookers. America must not remain silent.”

Two months after receiving Thay’s letter, on August 12, 1965, Dr. King addressed the annual convention of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Birmingham, Alabama. For the first time in his role as SCLC President, addressing his assembled colleagues and associates, he spoke about the war. “Few events in my lifetime have stirred my conscience and pained my heart as the present conflict which is raging in Vietnam.” Echoing Thay’s letter, King made clear his view that the Vietnamese people were not the enemy. “The true enemy is war itself,” he said.

Dr. King had long admired the Christian pacifist Abraham Johannes Muste, one of the

Founders of the Fellowship of Reconciliation in the United States, was one of the foremost proponents of nonviolence in the United States. Active in both the civil rights movement and nonviolent protest against Vietnam War, Muste sought to build a bridge between both struggles by engaging Dr. King in the growing antiwar movement. In furtherance of this goal, Muste arranged for Dr. King to meet Thich Nhat Hanh in person for the first time. On May 31, 1966, the two clergymen met in Chicago; they talked with moral urgency about the war, and about the imperative to foster peace, freedom and community in the United States, Vietnam and internationally.

This is how Thay describes the meeting: “The moment I met Martin Luther King, Jr., I knew I was in the presence of a holy person. Not just his good work, but his very being was a source of great inspiration for me…”

Martin Luther King Jr. & Thích Nhất Hạnh, Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation, https://thichnhathanhfoundation.org

In January 1967, in his role as the Nobel Peace Prize laureate of 1964, Dr. King wrote to the Nobel Institute to nominate Thich Nhat Hanh for the 1967 Nobel Peace Prize. “I do not personally know of anyone more worthy of the Nobel Peace Prize than this gentle Buddhist monk from Vietnam.” King described his friend as “an apostle of peace and non-violence, cruelly separated from his own people while they are oppressed by a vicious war which has grown to threaten the sanity and security of the entire world.” For the Nobel Institute to confirm the Peace Prize on Thich Nhat Hanh “would itself be a most generous act of peace,” as it would “revive hopes for a new order of justice and harmony.”

“The history of Vietnam is filled with chapters of exploitation by outside powers and corrupted men of wealth, until even now the Vietnamese are harshly ruled, ill-fed, poorly housed, and burdened by all the hardships and terrors of modern warfare. Thich Nhat Hanh offers a way out of this nightmare, a solution acceptable to rational leaders…. His ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity.” Martin Luther King, Jr.

Over the coming weeks, Dr. King began to speak out even more directly against the war in public statements that reflected the impact of Thay on his own thinking. Dr. Clarence B. Jones, who was Dr. King’s lawyer and strategic advisor, recalls how Dr. King privately shared with a small number of key advisors his inner struggle about the war. In the end, Dr. King emphasized that he was above all a minister of the gospel, and that he could not waiver from the dictates of his conscience, whatever the political cost. His receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize, and his call for Thich Nhat Hanh to be recognized with the same honor, only intensified his feeling of moral responsibility. King privately referred to Thay as his “brother,” and he spoke with admiration of Nhat Hanh’s example of courageous dissent, at far greater personal cost than anything that King would face in the United States. After Nhat Hanh’s example, he asked, how can I continue to remain silent on this issue?”

On February 25, 1967, Dr. King spoke to a large gathering in Los Angeles: “It is time for all people of conscience to call upon America to return to her true home of brotherhood and peaceful pursuits. We cannot remain silent as our nation engages in one of history’s most cruel and senseless wars.” (Martin Luther King, Jr. address to The Nation Institute, “The Casualties of the War in Vietnam”). Most powerfully, on April 4, Dr. King spoke to an overflow congregation at the Riverside Church, delivering one of the most powerful speeches of his career:

“I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today — my own government. For the sake of those boys, for the sake of this government, for the sake of the hundreds of thousands trembling under our violence, I cannot be silent.” Martin Luther King, Jr., “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence,” April 4, 1967.

As Thay had written, man is not the enemy of man, but war itself is our enemy. War, intolerance, fanaticism, dictatorship, cupidity, hatred and discrimination. For Dr. King, the Vietnamese were not our enemy, even the North Vietnamese Army, and the Vietcong. The enemy is war itself, systems that keep millions poor, and pervasive, structural racism. “Our only hope today lies in our ability to recapture the revolutionary spirit and go out into a sometimes hostile world declaring eternal hostility to poverty, racism, and militarism.”

A few weeks later, in May 1967, Dr. King met Thich Nhat Hanh for the second and final time, in Geneva Switzerland, at the Pacem in Terris conference organized by the World Council of Churches. According to the Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation website:

“Thay was staying on the fourth floor of the hotel, and Dr. King invited Thay to breakfast on the eleventh floor. Thay was detained by the press and arrived late. He was moved that Dr. King kept their breakfast warm and waited for him to arrive before eating. At this meeting, Thay told Dr. King, “Martin, you know something? In Vietnam they call you a bodhisattva, an enlightened being trying to awaken other living beings and help them go in the direction of compassion and understanding. Later, Thay said he was glad he had a chance to say this to Dr. King, because less than a year afterward, on April 4, 1968, Dr. King was assassinated in Memphis.’ https://thichnhathanhfoundation.org

The Rt. Rev. Marc Handley Andrus, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of California. has immersed himself in research and reflection on the the profound relationship between Thay and Dr. King. I am very excited that Bishop Andrus’s new book — Brothers in the Beloved Community: The Friendship of Thich Nhat Hanh and Martin Luther King Jr. (Parallax Press, 2021) — will be coming out very soon. I can’t wait to read it, and to have an opportunity to invite Bishop Andrus to speak about this powerful story.

Jonathan D. Greenberg