San Francisco-Birmingham Unity March, Market Street to City Hall, May 26, 1963, courtesy of Bancroft Library

Yesterday, for the second time in U.S. history, we celebrated Juneteenth as an official national holiday. I am grateful to have had a chance to read and meditate about the holiday.

This short essay reflects on the legacy of the first Juneteenth celebration, in Galveston Texas, on June 19, 1866, and the first Juneteenth Celebration in San Francisco, on June 19, 1945.

Introduction: History Matters

Yesterday, Nancy Pelosi issued a press release (“Pelosi Statement on the 157th Juneteenth Celebration”) affirming that the Juneteenth federal holiday was established in June 2021 as a result of the leadership of Houston Texas Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee and the Congressional Black Caucus, and in response to the Black Lives Matter demonstrations following the murder of George Floyd, perhaps the largest nonviolent protest movement in U.S. history. Pelosi emphasizes that the most important way to honor Juneteenth is “to root out the systemic bigotry that still plagues our nation,” including legislative efforts to enact the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, and “to uphold Americans’ sacred right to vote” by enacting the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, and the For the People Act.

Pelosi’s analysis is true to the spirit of Juneteenth, which demands that we rededicate ourselves, and act with fierce determination, to advance the struggle for racial justice in our nation today. Increasing accountability for police misconduct is imperative, and we cannot rest until we honor the voting rights legacy of John Lewis in an era of intensified white backlash, when Jim Crow strategies of disenfranchisement are spreading across the country under new forms. Pelosi powerfully concludes her Juneteenth statement with John Lewis’s words: “Ours is the struggle of a lifetime, or maybe even many lifetimes, and each one of us in every generation must do our part.”

However, there is one mistake in Pelosi’s statement: this weekend is the 156th Juneteenth Celebration, not the 157th. Pelosi’s mistake is ubiquitous, and entirely understandable – the Juneteenth Foundation, for example, makes a similar error.

The issue here has nothing to do with arithmetic — it is about the nature and purpose of collective memory. I highlight this mistake not to be fastidious or narrowly academic, but to highlight the meaning of Juneteenth, and its urgent importance for our nation — and the special meaning of Juneteenth for San Francisco, our city.

From the Deep South — West to Texas

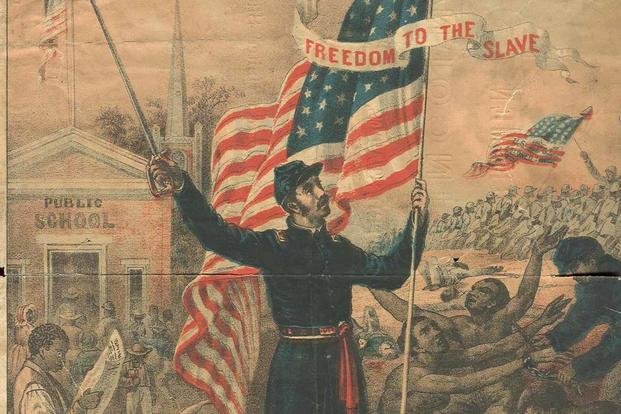

The first Juneteenth celebration took place in Galveston Texas on June 19, 1866 — exactly one year after Union Army General Gordon Granger issued “General Order Number 3” on June 19, 1865 (“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves…”). As Henry Louis Gates, Jr, explains, PBS African American History Blog:

“Since the capture of New Orleans in 1862, slave owners in Mississippi, Louisiana and other points east had been migrating to Texas to escape the Union Army’s reach. In a hurried re-enactment of the original Middle Passage, more than 150,000 slaves had made the trek west, according to historian Leon Litwack in his book Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery. As one former slave he quotes recalled, ” ‘It looked like everybody in the world was going to Texas.’ ”

When Texas fell and Granger dispatched his now famous order No. 3, it wasn’t exactly instant magic for most of the Lone Star State’s 250,000 slaves. On plantations, masters had to decide when and how to announce the news — or wait for a government agent to arrive — and it was not uncommon for them to delay until after the harvest. Even in Galveston city, the ex-Confederate mayor flouted the Army by forcing the freed people back to work, as historian Elizabeth Hayes Turner details in her comprehensive essay, “Juneteenth: Emancipation and Memory,” in Lone Star Pasts: Memory and History in Texas.”

“Those who acted on the news did so at their peril,” Gates explains, recounting stories of former slaves lynched in the immediate aftermath of Granger’s announcement, because they abandoned their former enslavers.

“Hardly the recipe for a celebration — which is what makes the story of Juneteenth all the more remarkable. Defying confusion and delay, terror and violence, the newly “freed” black men and women of Texas, with the aid of the Freedmen’s Bureau (itself delayed from arriving until September 1865), now had a date to rally around. In one of the most inspiring grassroots efforts of the post-Civil War period, they transformed June 19 from a day of unheeded military orders into their own annual rite, ‘Juneteenth,’ beginning one year later in 1866.”

This history reveals deeper layers of meaning for Black Americans, and for all Americans:

The establishment of Juneteenth by former slaves as a celebration of freedom was an act of defiance and courage in an environment of continued oppression.

More accurately, establishing the Juneteenth holiday was a defiant commitment to collective memory.

Juneteenth is a promise, as a community, and now as a nation: To remember the relentless atrocity of slavery, the untold cruelty, the complete, massive, day to day violation of human dignity; to never forget that we were slaves; To remember and celebrate emancipation, to appreciate the meaning of freedom, and its priceless value, to never take it for granted; To remember that no person can be free until all people are free; To carry forward this precious inheritance of collective memory, from generation to generation, by participating in communal and civic activities of remembrance and celebration every year on June 19; and To rededicate ourselves to the fight for racial justice, truth and reconciliation,, throughout our nation, and everywhere we live — from Buffalo New York to Uvalde, Texas, from Washington D. C. to San Francisco, home of our USF community, where Juneteenth has its own unique and powerful history.

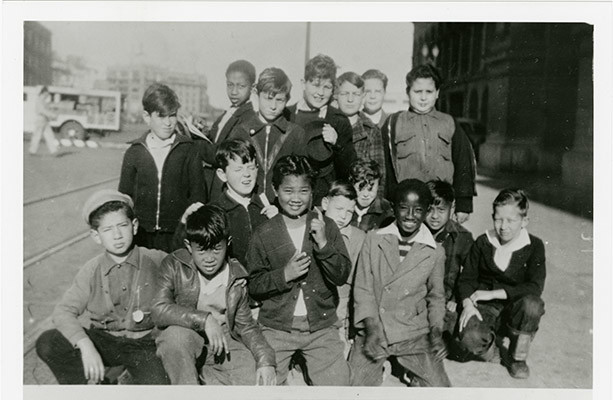

Students in the Fillmore District, San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

From Texas — West to San Francisco

I wish to thank historian Emily Blanck for her fascinating recent essay, from which I learned about the strong multigenerational connection between the newly freed slaves in Galveston Texas and the “Harlem of the West” in the Fillmore District of San Francisco’s Western Addition. Blanck, “Galveston on San Francisco Bay: Juneteenth in the Fillmore District, 1945–2016,” Western Historical Quarterly, Volume 50, Issue 2, Summer 2019, Pages 85–112. Reading this essay, I was dumbfounded to learn that “San Francisco’s Juneteenth holds the unique distinction of being the longest continuously running urban Juneteenth celebration either inside or outside of Texas.”

The robust, embedded experience of Juneteenth in San Francisco has nothing to do with the shameful history of slavery, involuntary servitude, and genocide here in California, a history that requires new forms of collective remembrance that are only beginning to emerge.

Rather, Juneteenth in San Francisco is an amazing story of cultural inheritance and transmission — from former slaves in Galveston, Texas to Black immigrants to San Francisco’s dynamic urban landscape — and the adaptation of this inheritance to new, rapidly changing socio-economic realities, racial demographics and political struggles.

In the early years of the 20th century, and the subsequent decades, six million Black Americans fled the Deep South and Texas. They headed to the Midwest (Chicago, St. Louis, Detroit, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Kansas City, Milwaukee etc.), and the Northeast (New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, etc.) and West, primarily to California. They fled the entrenched system of economic and racial oppression in the former Confederate states — subsistence employment and indentured servitude, sharecropping, convict leasing, voter disenfranchisement, Lynch law, and Jim Crow apartheid — for jobs in the defense and shipbuilding industries in San Francisco and the SF Bay Area.

As greater numbers of Black immigrants arrived in San Francisco to escape the South and take advantage of job opportunities, they were welcomed by an increasingly entrenched system of racial segregation; racist housing practices, restrictive covenants, and redlining by banks and the federal home loan protocols made it nearly impossible for Black residents to purchase homes. Only two neighborhoods welcomed Black families without restriction: Bayview/Hunter’s Point. and the Western Addition — with Fillmore Street at its heart. The Fillmore District was unique, “one of the most integrated neighborhoods west of the Mississippi.”

In 1944, amidst this dynamic social and cultural environment, the great African American theologian Howard Thurman, whose grandmother had been a slave, came to San Francisco to establish and serve as co-pastor (with Dr. Alfred G. Fisk) of the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples, the first racially integrated church in the United States.

Spiritual dynamism, infused with Black culture, and mixed with Buddhist as well as Christian and Jewish streams, is part of San Francisco’s DNA.

So is Black music, especially jazz and blues.

Over time, as the Fillmore became home to an explosion of Black cultural activity, it became known as “the Harlem of the West.” See Elizabeth Pepin Silva and Lewis Watts, Harlem of the West: The San Francisco Fillmore Jazz Era, (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2006), Heydey Books, 2020.

Wesley Johnson and the Texas Playhouse

Patrons at the Texas Playhouse, early 1950s. From Wesley Johnson Jr. (Silva and Watts)

Fillmore’s clubs attracted biggest stars in the world of jazz and blues: Billie Holiday sang at the Champagne Supper Club and the New Orleans Swing Club and Bop City, which became the hottest place of all, hosting Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Ben Webster, Billy Eckstine, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Dinah Washington, John Handy, and John Coltrane. Dexter Gordon joined the house band at Bop City, and Sammy Davis, Jr. joined band on bongos; Louis Armstrong and T-Bone Walker held court at Wesley Johnson’s Club Flamingo, a popular local hangout at 1836 Fillmore Street – also known as the Texas Playhouse.

Johnson, a Texas refugee, is the central player in this story of cultural transmission from Galveston to the Fillmore.

Club owner Wesley Johnson Sr. behind the bar at the Texas Playhouse, 1836 Fillmore, circa 1958. Photo by Harry Cox (Silva and Watts)

Wesley Johnson Sr. (left) with T-Bone Walker and an unidentified woman at the Texas Playhouse, late 1950s. (Wesley Johnson Jr. Collection, Silva and Watts)

On June 19, 1945, in dramatic Texas fashion, Wesley Johnson brought Juneteenth to San Francisco: riding down Fillmore Street on a white stallion, wearing a white cowboy hat, he opened up the Texas Playhouse for the city’s first Juneteenth celebration.

And he did the same year after year for decades going forward.

“The small nightclub celebrations in the 1940s grew to be San Francisco’s major Black summer festival in the 1960s and have been continuously celebrated to the present…. Juneteenth remained relevant in San Francisco because it became intertwined with the history of African Americans in the Western Addition neighborhood.” (Blanck).

Thus, across the decades since Wesley Johnson introduce Juneteenth to the Fillmore community in a down-home style at the Texas Playhouse in 1945, San Francisco has celebrated Juneteenth for 77 years – the longest continuous urban celebration of Juneteenth in the nation, including in Texas itself.

But this story is not simply a story about celebration, and the implantation of Texas Black culture to the City by the Bay.

Like Juneteenth itself, it is a story about mourning as well as joy.

In 1953, city politicians targeted Black neighborhoods in the Western Addition for “redevelopment.” Of those evicted, 72 percent were African American, although the Black population comprised around 10 percent of the city’s population.

Black San Franciscans saw their neighborhood as vibrant and exciting, if crowded. But city officials saw dilapidated buildings, liquor stores, barber shops, nightclubs, and non-White faces; and they described the neighborhood as a “slum.” (Blanck).

On June 19, 1964, Johnson again rode his white horse, in white cowboy garb, down Fillmore Street, as Grand Marshall.

But this Juneteenth was different. For the first time, Johnson as Grand Marshall led a neighborhood parade to launch an extended three-day, three-night Juneteenth celebration for the entire San Francisco Black community leadership.

“San Francisco’s Fillmore district needed a community holiday, because 1964 began the second and most devastating stage of urban renewal in the Fillmore District. As the city literally tore down their buildings, the Black community responded by claiming the streets for their own. That street festival continues today. Although Johnson would not be Grand Marshall again until 1976, the Grand Marshalls of the Juneteenth parades continued to ride a white horse and wear a white cowboy hat as Johnson had.

Johnson’s Juneteenth celebrations expanded outside the doors of his nightclub in the context of the 1960s, as a part of the community’s protest against redevelopment… In 1964, as the city restarted its redevelopment project, the community used Juneteenth as a big street gathering to claim the space as their own, taking the celebration out of Johnson’s nightclub and into the streets.

The 1964 celebration was the final one that bore Johnson’s face in its advertising and the first sponsored by the new Juneteenth Festival Committee. The advertisements that year bridged the old with the new. Astride his white horse, Johnson invited Black San Francisco to what was now a three-day Juneteenth festival at his two clubs, the Texas Playhouse and the Congo. Adding a parade, this longer festival was no longer only in the clubs; it catered to families too. Johnson served as Juneteenth 1964 served as a bridge to a refashioning of the identity of the Black community.”

Intensified political struggle — national and local

For San Francisco’s Black community, Juneteenth increasingly engaged political issues, and increasingly allied itself with the civil rights campaigns led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the emboldened student leaders of the Black Freedom Movement of the early 1960s. Identifying with their brethren fighting Jim Crow throughout the South, Black activists in San Francisco adopted tactics of nonviolent direct action and other forms of resistance to discrimination at home in interracial campaigns directed at some of the racist companies operating throughout the city. In 1963 and 1964, activists successfully picketed Mels Drive-In and the Sheraton Palace Hotel — and the Cadillac, Lincoln-Mercury and Chrysler dealerships on Van Ness — to demand that they hire Black employees. In May, 1964, Dr. King came to San Francisco to support the local movement, to link San Francisco campaigns to the larger national civil rights struggle, and to protest against the white backlash of discriminatory housing practices in California.

Martin Luther King, Jr., interfaith civil rights rally, San Francisco Cow Palace, June 30 1964, photo courtesy of George Conklin.

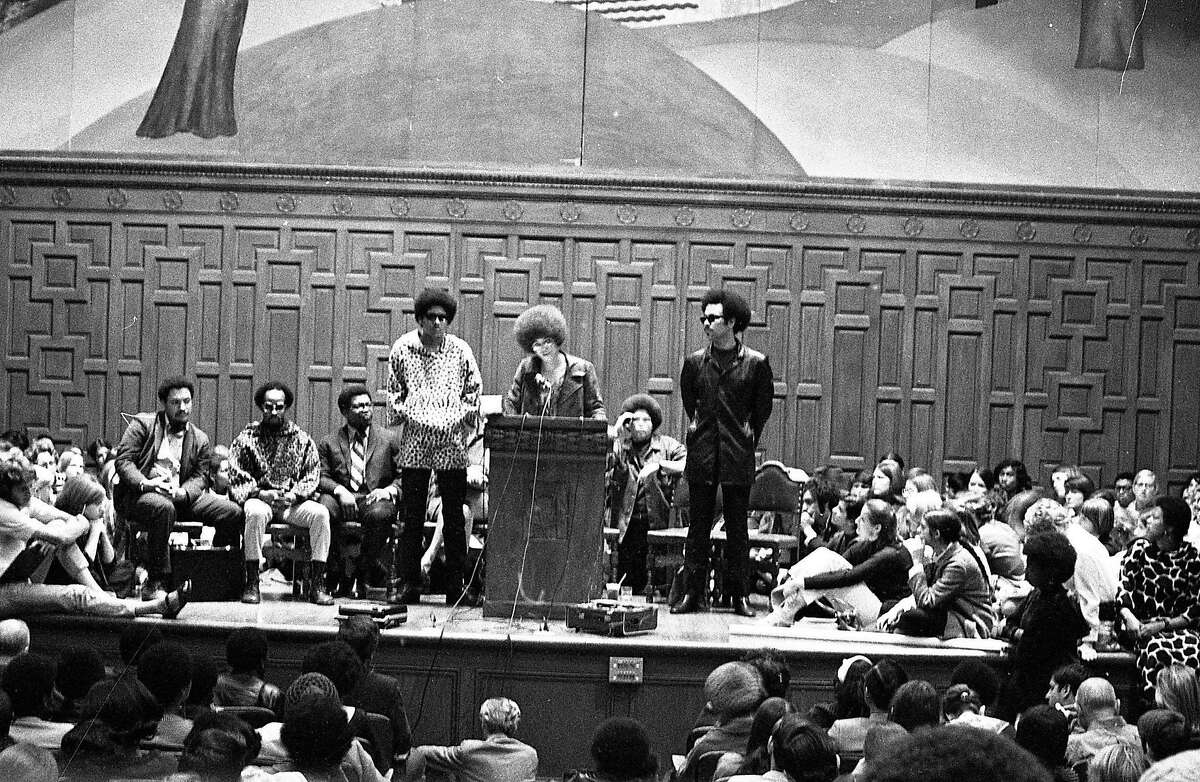

Racial struggles intensified, and radicalized, after Dr. King’s assassination, with the rise of the Black Power Movement, and the Black Panther Party, in San Francisco and Oakland.

San Francisco Black Panther Party newspaper, Jan. 24, 1970, photo courtesy of Steve Rhodes.

Concurrently with the increasing militancy of Black activists, “urban development” continued relentlessly, decimating Black neighborhoods in San Francisco, especially the Western Addition and the Fillmore.

“The predominantly black Fillmore district was destroyed in the early 1970s by the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency when, in a gross lack of understanding of the black community, it redeveloped “the ghetto” for new housing and commercial use. The agency’s ill-fated plan forced out 50,000 African Americans from the Fillmore district, an area known at that time as the Harlem of the West.” Fred Jordan, “San Francisco continues destruction of its black community,” San Francisco Chronicle, April 28, 2016.

An aerial view of the Fillmore Center site of the Western Addition redevelopment project in the early 1970s.; Photo from San Francisco Redevelopment Records, San Francisco History Center, S.F. Public Library

In San Francisco, officials used redevelopment funds to demolish the Western Addition with the promise to build modern housing. Municipal promises made became promises broken almost immediately. They demolished or evacuated buildings quickly and rebuilt slowly to refashion San Francisco. Large vacant lots dominated the Western Addition, and housing became even harder to find.

“Amidst this devastation, Juneteenth became a tool of resistance… The community, in defiance of the lifeless lots and alongside many other forms of protest, held a festival that demonstrated their resilience and respectability.” (Blanck)

During the 1970s, there were a few years where no Texas city had a public Juneteenth holiday. Throughout these years, San Francisco remained a Mecca for annual Black community Juneteenth celebrations.

In 1980, Wesley Johnson was selected once again as Grand Marshall and the two days of celebrations included a rodeo. But by then thousands of San Francisco’s Black families had been forced from their homes, never to return. In 1980, the Juneteenth narrative focussed less on depressing local problems and more on the story and legacy of liberation from slavery in Galveston, Texas.

At this point in the story, another former Texan enters the picture. Like Johnson, Willie Brown was born and raised in Texas poverty (“I was not born in a log cabin… I was born under a log cabin.” Blanck). Brown’s family lived in Mineola, a segregated town in East Texas mire in racial violence and white supremacist terror. The fourth of five children in the family, Brown worked as a shoeshine boy in a whites-only barber shop, and took jobs as a janitor, fry cook and field hand during his years as a student at Mineola Colored High School. In segregated, Mineola, the celebration of Juneteenth was a very important annual event in Black neighborhoods. Brown remembers playing baseball in the Black little league Juneteenth competition, and enjoying the annual Juneteenth feast, centered around a barbecued billy goat. Like Johnson, Brown brought his Black Texas roots, down-home Texas style, and Texas-sized personality to his adopted City by the Bay, along with a genius for cultural entrepreneurship and reinvention in the face of adversity.

The racially integrated Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples founded by Rev. Howard Thurman in 1944 continued to thrive, as it does to this day. The eclectic spiritual fire Thurman lit, and the spiritual home he found, in San Francisco continued to birth new churches and congregations infused with Black cultural and religious dynamism, and the power of Black music and spirituality, even as as the city’s Black community struggles to survive under extremely difficult employment, housing, and affordability challenges.

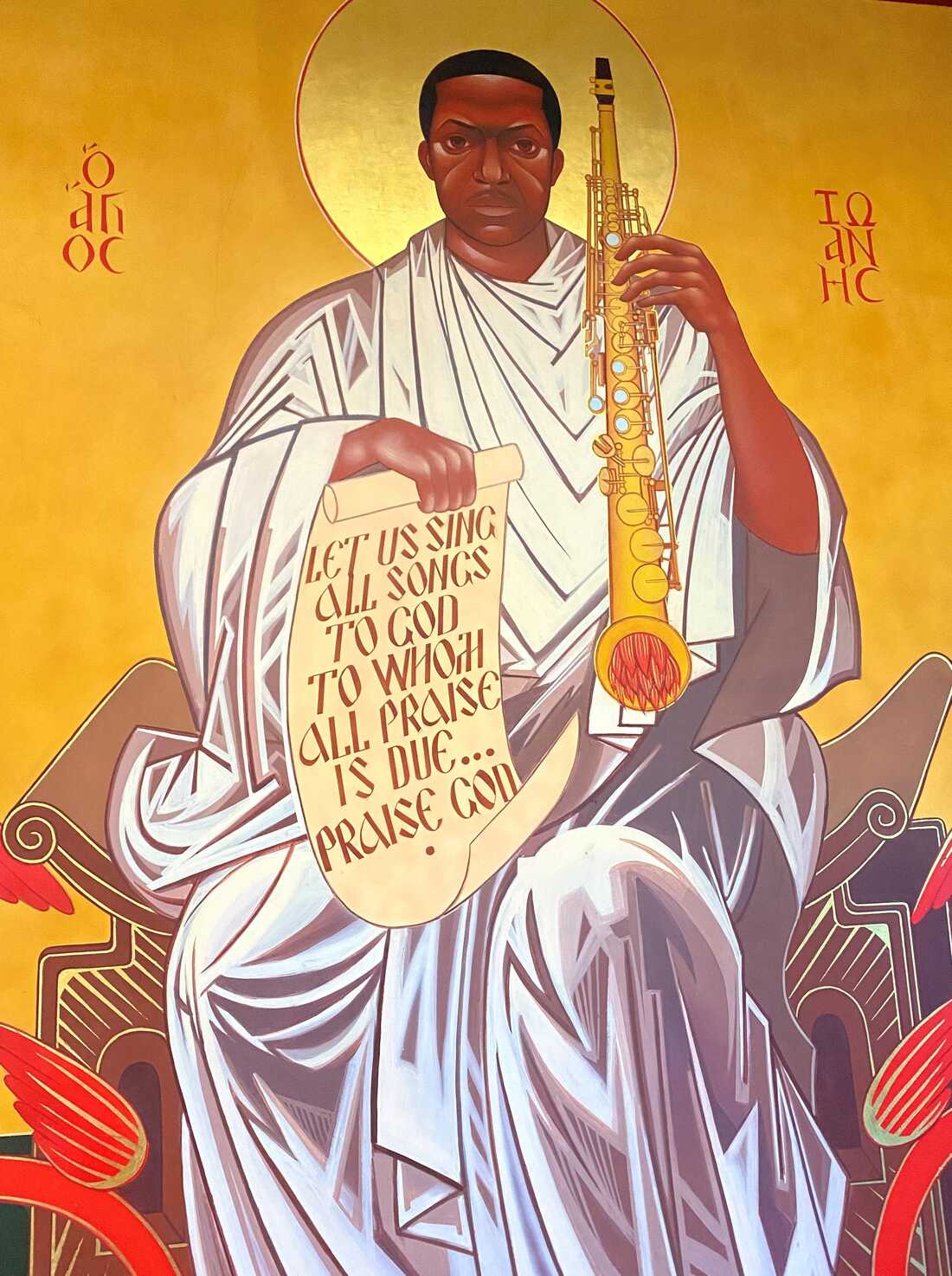

In 1965, Franzo and Marina King went to see John Coltrane play at a packed Jazz Workshop in the Fillmore. For the Kings, the Holy Spirit had come down to join Coltrane on the stage that night. “I think we were both slain in the spirit,” Franzo King recalls. “It was like getting caught up in a rainstorm. And we didn’t know if it was going to bring a flood or flowers.” (“Five Decades On, An Eclectic Church Preaches The Message Of John Coltrane,” NPR, September 23, 2020.). Inspired by this conversion experience, the Kings

co-founded the St. John Will-I-Am Coltrane African Orthodox Church, with a thriving if small congregation, visitors from all over the nation and the world, and a jazz-filled liturgy centered by Coltrane’s A Love Supreme.

A Byzantine-style icon of John Coltrane at the church. The inscription to the left and right of Coltrane’s body reads, in Greek, “St. John.”

In a recent interview on local San Francisco radio, former Mayor Willie Brown was asked to share his feelings about the establishment by Congress of Juneteenth as a federal holiday. In his characteristically irreverent style, Brown responded that the new federal holiday is “nonsense” — without a Congressional enactment of voting rights legislation.

156 years after the first Juneteenth Celebration in Galveston Texas in 1866, and 77 years after Wesley Johnson welcomed the Fillmore community to the Texas Playhouse to celebrate Juneteenth in 1945, the tradition continues to have deep meaning.

Juneteenth is always about racial justice, freedom and power.

About making it real.

William Brown, 10, rides in a Juneteenth event was organized by the Circle L Five, the first African-American riding club in Texas. Photograph courtesy of Ron McKeown, 1975, Creative Commons

Jonathan D. Greenberg, Juneteenth, 2022