It’s a brisk winter weekend in 2014, a week before my seventeenth birthday, and I have plans to meet a very special person across from the UC Berkeley campus. The sky is a pale, ice blue, patches of sunlight melting through the clouds. I stand in one of these patches of light, hands in my pockets, nervously glancing up and down Shattuck Avenue. When I see her, my heart dives deep into my stomach. Overthinking every step along the way, I stand up straighter and walk toward her, my hands balled up into fists in my jeans pockets.

A first date is always a daunting prospect, especially at the formative, vulnerable, and unforgiving age of seventeen. The unspoken rules of being are just beginning to be enforced, and you find yourself squeezed and stretched by an unseen mold.

My companion’s pixie cut lifts and swirls in the gentle breeze of a Bay Area winter. She is wearing a blood red turtleneck, carrying her camera and some books in a tattered tote bag. This is our first date and we’re going to see a movie. The film of choice is Inside Llewyn Davis, a dimly lit and artfully shot movie about a folk singer who suffers from depression. Ah, the romance…

Isabel and I fell in love with the movie’s sappy soundtrack; we had a penchant for all things angsty. We thought ourselves a pair of cinema connoisseurs, scoffing at the blockbusters that dominated our local movie theaters, and making the trek from our respective hometowns to meet in Berkeley. The movie is simultaneously endearing and heart wrenching. We watch enraptured as a pre-Star Wars Oscar Isaac and post-Gatsby Carrie Mulligan inhabit the lives of two struggling musicians in New York City, 1961.

About three quarters of the way into the film, our protagonist sits across from his senile father, serenading him for the first time in years. I feel a lump building up in my throat. I tilt my head slowly to one side, my eyes squinting against the brightness of the movie screen. As tears begin to well up, I feel a wave of emotions wash over me: heartbreak and sorrow for the film’s protagonist; excitement at being in a beautiful theater with a beautiful girl; but mostly an overwhelming sense of trepidation and embarrassment. Am I really going to cry right here, right now?

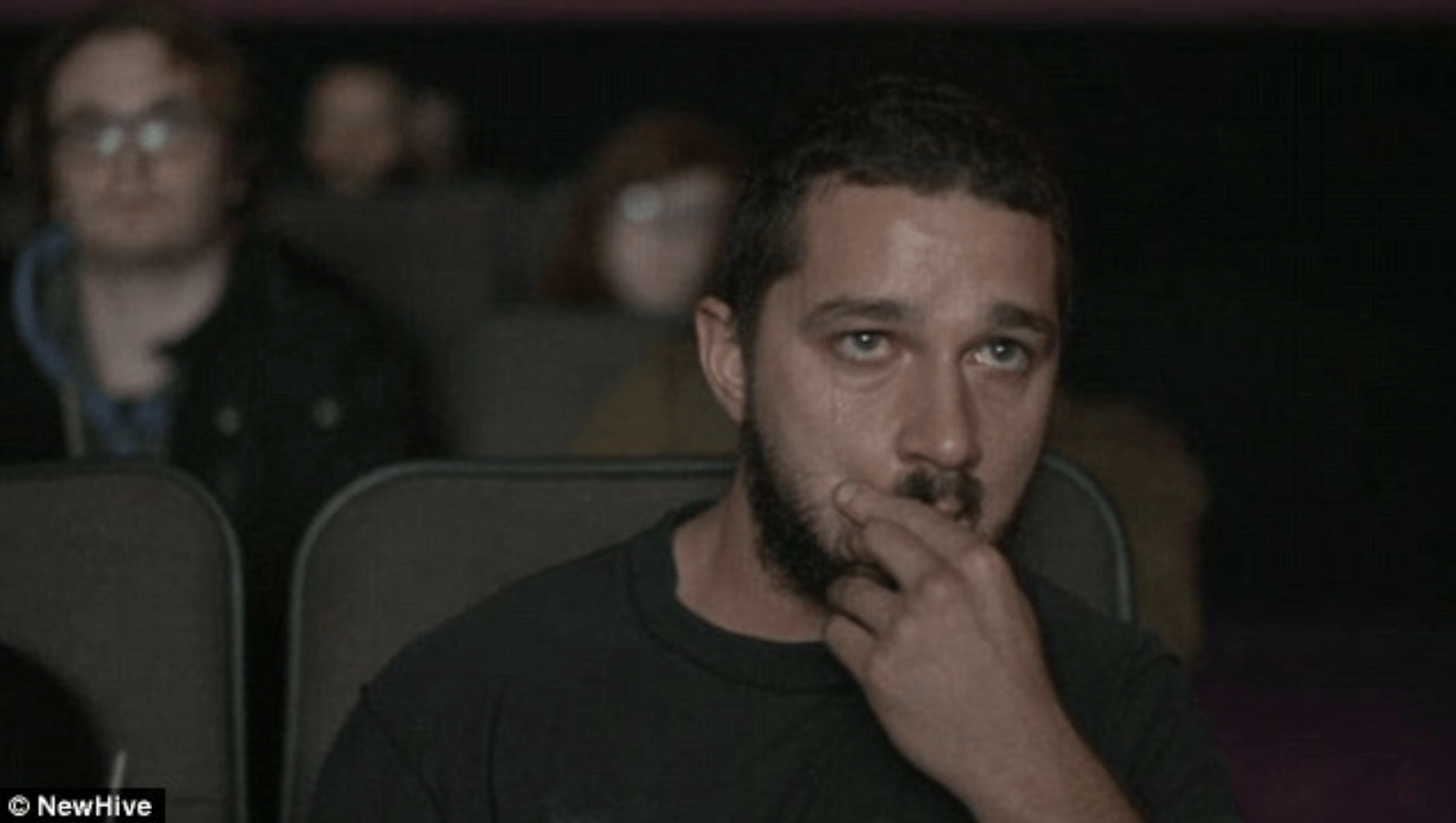

I quickly accept my salty fate and start to brainstorm ways to cry inconspicuously. What would be the best way to cry? Agitatedly, I form my right hand into a fist and stick the knuckle of my index finger in between my teeth. With my elbow on the armrest, I focus hard on the screen. If I don’t look at Isabel, she won’t notice, but as Llewyn Davis looks his decrepit father in the eyes, I can’t help but let the tears fall.

And boy, do they fall.

Without making a sound, I look ahead as heavy droplets roll down my cheeks like raindrops down a windowpane. My cheeks grow dewy with tears, and I begin to feel Isabel’s presence next to me more acutely, as if I am sitting next to the sun. I eventually cave and look at her. Our eyes meet for the first time since the movie began, and she notices my glistening face and shiny red eyes. I let out a panicked chuckle. In the dark of the movie theater, I can barely make out her faint smile as she wipes my face.

She never brings it up. Some time later, when I ask her what she thought of the incident, she says, “It was sweet.” A sort of weight comes off my shoulders when she says this. Relief.

Growing up I was never the most masculine guy around. Ever. I never enjoyed watching or playing sports, didn’t hesitate to surround myself with girls, and never feared a display of emotion. And I seldom felt bad about my refusal to conform, but for some reason, everyone around me felt it was their duty point this out.

Isabel and I went on to form a remarkable bond; she would see me cry a good half dozen times or more. Even today, despite no longer being romantically involved, there is no awkwardness to our dynamic. There’s no toxicity or staleness, and if I had to guess, it’s because we saw each other not as a collection of concepts or ideals, but as flawed and spectacular people. We wanted to be with each other for who we were, not for what we expected.

Now, four years later, free from the angst of adolescence, I’m grateful for my unfettered expression. There is no greater evolution that occurred in my youth than the permission I gave myself to simply be, regardless of expectation and norms.