Tucked away from the furious clash of color and texture that spills out of every gift shop on San Francisco’s Grant Avenue, Rainbow Sign & Art is in a basement. The only signage is a sandwich board that comes up to passersby kneecaps. It’s the kind of place you only come to when you know exactly what you want.

In the shop, cracked glass display cases house rows of earth-colored Chinese chops, dusty and waiting to be claimed. They are 2-inch-long elongated rectangles, some with decorative carving on the side, but blank on the bottom side.

In the shop, cracked glass display cases house rows of earth-colored Chinese chops, dusty and waiting to be claimed. They are 2-inch-long elongated rectangles, some with decorative carving on the side, but blank on the bottom side.

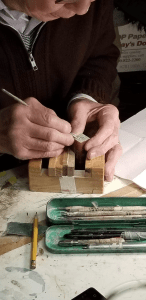

John Wong, the carver of these chops, is an expert in his craft. His wife Yihuang Wong showed me a business card explaining that Mr. Wong went to a renowned art academy in China. He also has a Certificate of Honor from former San Francisco mayor Willie Brown Jr., thanking Wong for his contributions to the community.

I stood in the shop for a while, attempting to remember any of my forgotten Mandarin, and looking at the small red squares that were stamped on nearly every of the room. These bright red squares are the seals created by chops.

At one point, a 40-something man came flying down the staircase, shouting. He and Ms. Wong plunged into a debate, gesturing to the zodiac calendar on the wall. Mr. Wong joined the conversation after a bit, still holding a block with a half-carved chop in it. The man, whose name I never caught, turned to me and explained in English that the chop in Mr. Wong’s hand was his purchase. It was a gift for his granddaughter, who was turning one right on the cusp of the Lunar New Year. He’d come to confirm with the Wongs which year they should be celebrating for her.

I asked him to translate a question for me, and after translating Mrs. Wong’s answer, he rushed out of the store. My question was: what does Mr. Wong carve into the chops most often? Mrs. Wong said he carves names.

She picked up a tattered book from the countertop that I’d assumed was a dictionary. It was a book of Western names made into Chinese characters. One page had reference headings for Glenarthur and Glotzbach. Near the book were a couple of bright red tins of the stamping paste used to make the seals. The chop owner places the carved side in the concoction of cinnabar and oil (in ancient times honey and cinnabar), and presses the dyed end onto a flat surface, leaving behind the seal. Each chop, just like each owner, is unique.

People at all levels of society in China own chops. One-year-olds own chops, and the Chinese government has their own chop. The Chinese government’s seal is nowhere to be found online. Nonetheless, according to Mark Mir, an archivist at the Ricci Institute for Chinese-Western Cultural History, the official seal of China has a whole person dedicated to it. “They get somebody that actually, BOOM, does that,” Mir said, pantomiming placing something heavy onto the table. The government of Taiwan has a page of their website devoted to their official chops.

While the seals made by chops in Wong’s shop are only about ½ inch by ½ an inch, this seal’s surface covers just over a quarter of your average sheet of paper. It’s ocean green jade and weighs seven pounds. The Taiwanese government’s seal can ratify, officiate, and confirm documents.

In China, companies have their own seals that carry similar powers. In fact, in some cases, the seal is the company, according to Deb Weidenhamer, CEO of multinational firm American Auction company. Writing for her New York Times blog, Weidenhamer recalled what a general manager in China said to her when she asked him to resign. “The controller of the chop is the controller of the company,” he said. “Good luck without it.” Apparently, he took her chop hostage, although through negotiation, she got it back.

In China, companies have their own seals that carry similar powers. In fact, in some cases, the seal is the company, according to Deb Weidenhamer, CEO of multinational firm American Auction company. Writing for her New York Times blog, Weidenhamer recalled what a general manager in China said to her when she asked him to resign. “The controller of the chop is the controller of the company,” he said. “Good luck without it.” Apparently, he took her chop hostage, although through negotiation, she got it back.

Imagine this kind of power in a dynasty. The first user of a chop was Emperor Qin Shi Huang, who came to power in 221 B.C. When he used his custom jade chop, people saw this as declaring the mandate of heaven. “Writing was always sort of associated with a sense of power,” said John Stucky, a librarian for San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum. “[Seals] grow out of the development of writing in China.” Emperor Qin standardized the script used on chops. When he unified China, he eliminated the oldest form of script, and required that a smaller script called Hsiao Chuan (“small seal script”) be used. This form, which was “characterized by symmetry, suppleness, and graceful lines and curves,” according to T.C. Lai’s book “Chinese Seals,” is still used.

The seals of Chinese citizens remain politically legitimate today in China. They are used similarly to Western signatures, confirming someone’s identity when opening a bank account, for example. However, Chinese citizens’ can have multiple names, and multiple seals, unlike Americans who are expected to use the names on their birth certificates for official documents. “Names change throughout your life,” said archivist Mir, with a smile.

A chop could have a childhood name, which is like a pet name, but known in China as a “milk” name. It could also have an honor or title, or a name in Western letters, or a school name, a work name, a pen name, a style name (like a courtesy name), a pseudonym, a temple name for religious business, or a posthumous name to be called post-mortem. According to Lai’s book, the accumulation of names by men in power can be a “romantic indulgence.” Each of these names are intentionally chosen. The Chinese languages have many homonyms, and therefore many ways of writing one name, according to Karen Fraser, University of San Francisco professor and Asian art historian.

Fraser gave the example of her own name, which translates as “flower circle.” She owns two chops. “Ka-Ren is the name pronunciation,” she said. “There are literally dozens if not more choices for the ‘Ka’ character and literally dozens if not more choices for the ‘Ren’ character. So, when Chinese or Japanese people are named, those characters are designated.”

How the chop is carved is important, because chops themselves are an art form. Chop carvers must able to write calligraphy and carve. Mir, the archivist, showed me several books, each dedicated to the work of a single famous carver.

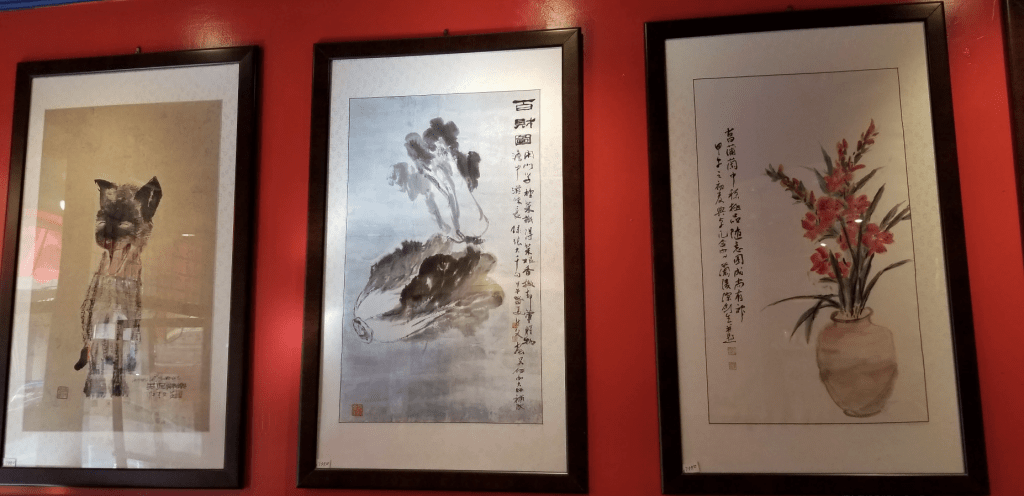

Sam Bernstein is a Chinese art collector in San Francisco who has bought and sold many seals. He said both the artist and the owner contribute to the value of a seal. “When you collect an old seal, you’re not just reading it,” Bernstein said. “You have to put the inscription and the name into an art historical context and that provides you with a much clearer understanding of the purpose of the seal.” A seal’s owners and creator can be tracked through its use on other art. Say, for example, an artist finishes a landscape painting, they stamp their seal on the piece.

If they work for a studio, the studio adds its seal. If the artist also writes calligraphy, they might write a poem on the painting.

Fraser, the art historian said, “People looking at that art might actually respond to that poem, write their own inscription, and then they would sign their own seal as well.” Thus, Chinese art sometimes has full columns of seals running up the sides – a “visual history” of its past authors, owners, and contributors, Fraser said.

Visual histories are everywhere in San Francisco’s Chinatown. I counted several dozen individual seals on paintings in my lunch restaurant alone. But as many seals as there are, John Wong is the only chop carver left in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

When I went zigzagging up and down Grant Avenue, popping into every jewelry, antique, and souvenir shop I could find to look for and ask about chops, I couldn’t find any. Many shop employees thought I was talking about something else, like chopsticks, before remembering chops. They told me they didn’t sell chops, with a look that told me it was silly to ask.

When I went zigzagging up and down Grant Avenue, popping into every jewelry, antique, and souvenir shop I could find to look for and ask about chops, I couldn’t find any. Many shop employees thought I was talking about something else, like chopsticks, before remembering chops. They told me they didn’t sell chops, with a look that told me it was silly to ask.

In Man Hing and IMPORTS, a clerk named Susanna told me Rainbow Sign and Art is the only place left to find chops in Chinatown. “Don’t waste your time” she said. “It’s just the one old couple. Everyone else retire.”

She seemed a little sad as she told me that she doesn’t think the younger generation here wants seals. “They make too much money,” she said. But historians and collectors are still interested in chops. Fraser said contemporary artists use seals on two-dimensional art. And thanks to the growing wealth of knowledge to be gained from and about seals, Bernstein said the market for chops remains strong. There was even a chop carver who worked in the Asian Art Museum’s store until he retired in 2017.

John Wong may be the only active carver left in Chinatown, but he still has plenty of chops in his cases to carve. People walking into the Wong’s store can, for $30, buy something small but significant. Seals are far more than a name. Seals are far more than a name.