Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, An Intersectional Analysis

Directed by Spike Lee, the 1989 comedy-drama Do the Right Thing focuses on a sweltering summer day in the Bedford-Stuyvesant district of Brooklyn. It explores the racial tensions that arise between Italian-American pizza owners and the local African-American residents, capturing their hate and violence. When examined critically, this film engages in racial and gendered discourses that highlight certain ideologies currently impacting our world. More specifically, Do the Right Thing explores the ways in which white hegemony exists as an unspoken but destructive force, impacting people of color in detrimental ways. Furthermore, the characterization of Lee’s Black female cast illustrates how the experiences of women of color are consistently left out of social and political conversations. When viewed through discourse analysis, Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing exemplifies how representations of race and gender perpetuate the hegemonic ideologies that govern our reality.

Discourse analysis is a tool used to dissect how knowledge production translates into the creation of our social reality. It proposes that audiences view media critically to produce a shared knowledge, establishing viewers as active participants in shaping our social world. And since our social world is ruled by hegemonic ideologies, it is critical to examine all the elements that play a part in its conservation. Systems of power must be studied under an intersectional lens, pulling different social categorizations into conversation about how our world is driven. As legal scholar Kim Crenshaw states in her essay Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color, intersectionality “highlights the need to account for multiple grounds of identity when considering how the social world is constructed” (2). She states that anti-racist and feminist practices have acted like they operate on different terrains on the field of power, but intertwining the two is vital in understanding how they dictate the ways bodies experience oppression and violence. Played out through a plethora of scenes, Do the Right Thing reveals how representations in the media are correlated with hegemonic power.

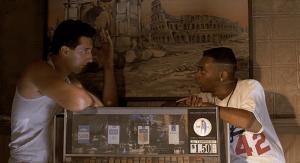

As scholar George Lipsitz states in his book The Possessive Investment in Whiteness, whiteness “never has to speak its name” or “acknowledge its role as an organizing principle in social cultural relations” (1). However, the lack of spotlight does not mean it is harmless. The possessive investment in whiteness still leads to violent consequences that perpetuate racist ideologies. Exemplified by an early scene in Do the Right Thing, Black protagonist Mookie asks his white coworker Pino to list his favorite celebrities. Mookie asks it casually while they’re on shift, luring him into exposing his racism. When Pino gives him his list of idols, who are all Black, Mookie confronts Pino on why he looks down on Black people when his favorite celebrities are all Black. Trying to defend himself, Pino explains that “they’re Black but not really Black. They’re more than Black. It’s different” (42). In this scene, it is clear from the way Mookie easily traps him using a series of simple questions that Pino has never confronted or questioned his racism. Stumbling over his words, Pino argues that his Black role models are different from Black people as a whole. His idols are “different” because they are successful and beloved by the public— two characteristics that he refuses to associate with the Black community.

As scholar George Lipsitz states in his book The Possessive Investment in Whiteness, whiteness “never has to speak its name” or “acknowledge its role as an organizing principle in social cultural relations” (1). However, the lack of spotlight does not mean it is harmless. The possessive investment in whiteness still leads to violent consequences that perpetuate racist ideologies. Exemplified by an early scene in Do the Right Thing, Black protagonist Mookie asks his white coworker Pino to list his favorite celebrities. Mookie asks it casually while they’re on shift, luring him into exposing his racism. When Pino gives him his list of idols, who are all Black, Mookie confronts Pino on why he looks down on Black people when his favorite celebrities are all Black. Trying to defend himself, Pino explains that “they’re Black but not really Black. They’re more than Black. It’s different” (42). In this scene, it is clear from the way Mookie easily traps him using a series of simple questions that Pino has never confronted or questioned his racism. Stumbling over his words, Pino argues that his Black role models are different from Black people as a whole. His idols are “different” because they are successful and beloved by the public— two characteristics that he refuses to associate with the Black community.

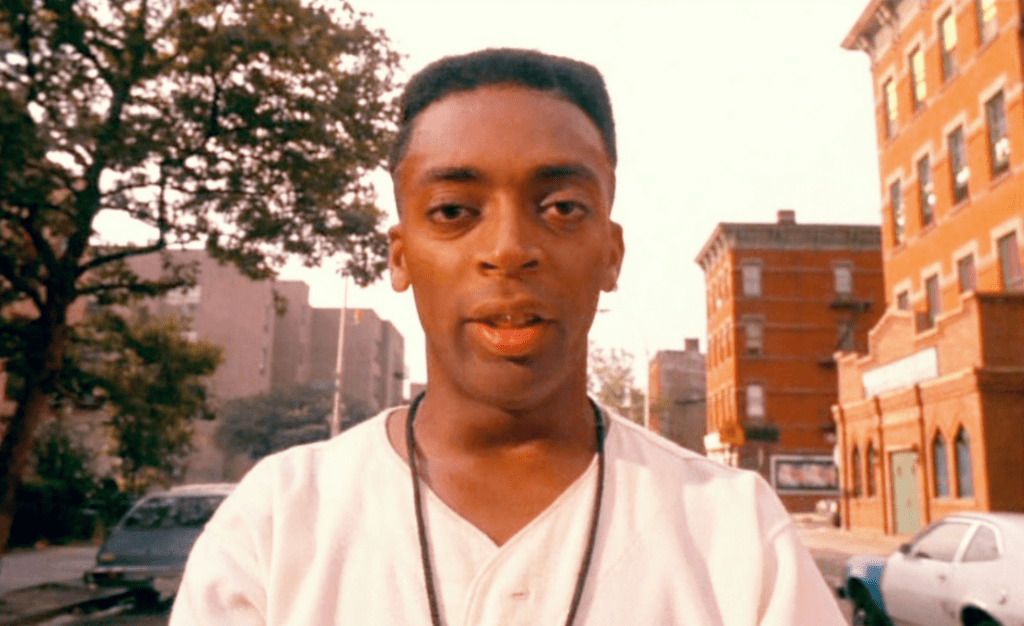

Lipsitz also explains how whiteness can be wielded as a weapon, which is represented at the end of the film when Sal and Radio Raheem get into a fight. Sal is upset at Radio Raheem for blasting his music on his boombox, while Radio Raheem gets defensive and refuses to turn it off. Their argument escalates into physical violence. Someone calls the cops, who upon arrival pull Radio Raheem, who is Black, off of Sal, who is white. Choking Radio Raheem too tightly and for far too long, the white cops end up killing him. But there are no consequences for their actions, which showcases how whiteness can be employed to impact communities of color in deeply traumatic ways. Additionally, a possessive investment in whiteness sustains itself “by pitting people against one another” (Lipsitz, 3). Racial triangulation—where Asian Americans are seen as the “honorary whites,” but never fully—turns minority groups into competitors. In Do the Right Thing, this concept is reflected in a scene where different characters break the fourth wall. Each character spits derogatory insults directed to another racial group, channeling their animosity towards the camera. Including words such as “ape,” “slant-eyed,” “Puerto Rican cocksucker,” “B’nai B’rith asshole” and more (43), the characters shed light on how strongly they clash due to differences in race.

Lipsitz also explains how whiteness can be wielded as a weapon, which is represented at the end of the film when Sal and Radio Raheem get into a fight. Sal is upset at Radio Raheem for blasting his music on his boombox, while Radio Raheem gets defensive and refuses to turn it off. Their argument escalates into physical violence. Someone calls the cops, who upon arrival pull Radio Raheem, who is Black, off of Sal, who is white. Choking Radio Raheem too tightly and for far too long, the white cops end up killing him. But there are no consequences for their actions, which showcases how whiteness can be employed to impact communities of color in deeply traumatic ways. Additionally, a possessive investment in whiteness sustains itself “by pitting people against one another” (Lipsitz, 3). Racial triangulation—where Asian Americans are seen as the “honorary whites,” but never fully—turns minority groups into competitors. In Do the Right Thing, this concept is reflected in a scene where different characters break the fourth wall. Each character spits derogatory insults directed to another racial group, channeling their animosity towards the camera. Including words such as “ape,” “slant-eyed,” “Puerto Rican cocksucker,” “B’nai B’rith asshole” and more (43), the characters shed light on how strongly they clash due to differences in race.

The film underscores this idea again at the end of the movie, when the mob finishes destroying Sal’s Pizza and turns to the Korean store to repeat the process. Although the Korean family has done no wrong, one of the Black characters says “It’s your turn” (83). The mob prepares to wreak havoc upon the store, seeing anyone who isn’t Black as an automatic enemy. Their eagerness to harm the Korean family illustrates how white hegemony is falsely framed as something achievable for communities of color, destroying their potential to form coalitions with one another.

Because they see the Korean family’s store as successful, like Sal’s Pizza, the Black community locates their racial status in close proximity to whiteness. But the Korean clerk responds to the threat by pleading “Me no white. Me black. Me black” (84), trying to communicate that he is one of them. Upon hearing this plea, one of the black characters recognizes that the two racial groups are actually on the same team. He confirms that “him no white” (84), and the mob finally lets the Korean clerk off the hook. By showcasing whiteness as a weapon to pit communities of color against each other and inflict violence, Do the Right Thing exemplifies how the possessive investment of whiteness preserves racism as a hegemonic ideology.

Because they see the Korean family’s store as successful, like Sal’s Pizza, the Black community locates their racial status in close proximity to whiteness. But the Korean clerk responds to the threat by pleading “Me no white. Me black. Me black” (84), trying to communicate that he is one of them. Upon hearing this plea, one of the black characters recognizes that the two racial groups are actually on the same team. He confirms that “him no white” (84), and the mob finally lets the Korean clerk off the hook. By showcasing whiteness as a weapon to pit communities of color against each other and inflict violence, Do the Right Thing exemplifies how the possessive investment of whiteness preserves racism as a hegemonic ideology.

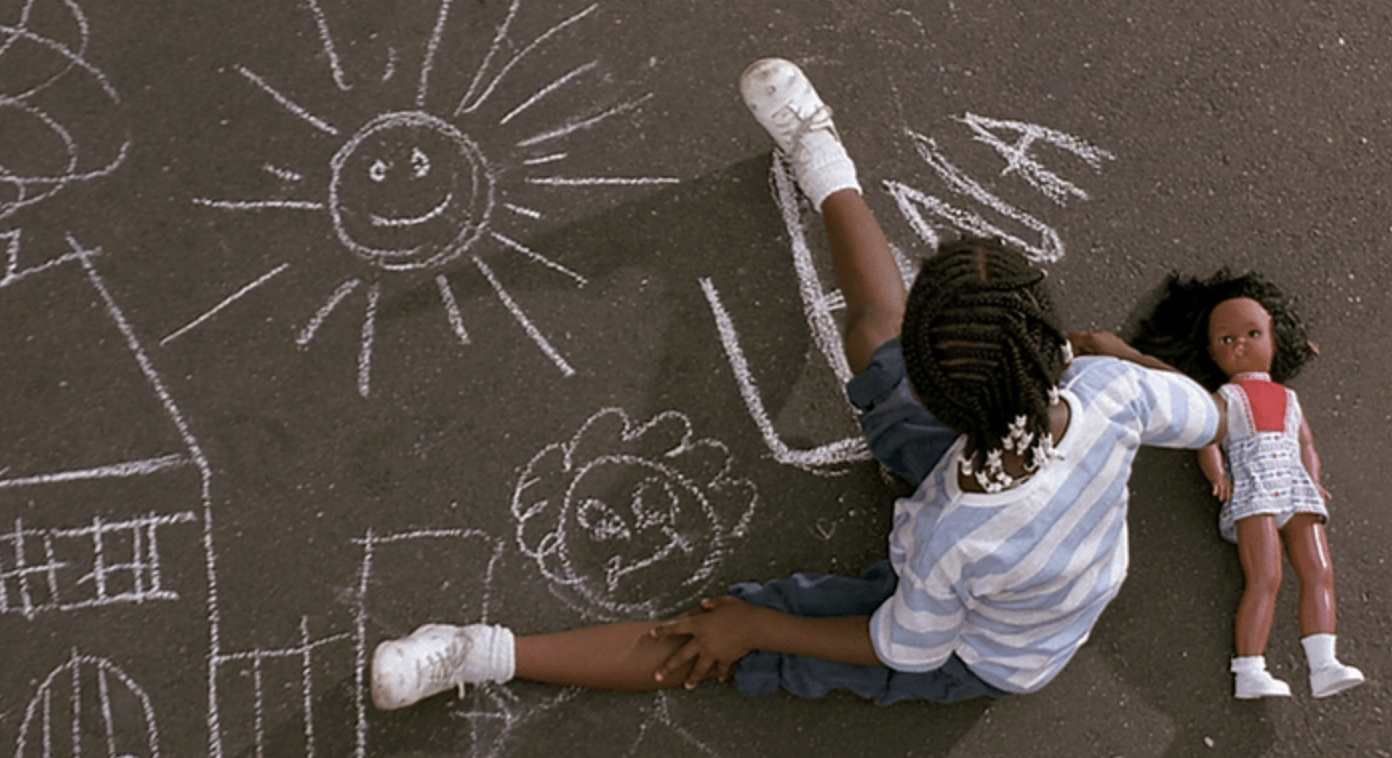

Do the Right Thing also engages in gender discourse, manifesting the racist conflicts within the early feminist movement through Lee’s female cast. Lee problematically frames his female characters solely as emotional guides or sex objects, leaving the heavy lifting of anti-racist activism to the men in the film. By failing to give depth and complexity to his Black female characters, Lee perpetuates the idea that Black women’s issues and ideas are less important than those of their male counterparts. This is illustrated in almost every appearance Mookie’s sister Jade makes, as she spends most of her time telling Mookie what to do. She is constantly reminding Mookie that he “should take better care of [his] responsibilities,” (48) egging him on like a concerned mother. For example, when she thinks Mookie’s frequent delivery detours are going to cost him his job, she even escorts him back to Sal’s Pizza herself. She asks Sal “how are you treating my brother?” (54), demonstrating her investment in their work relationship, even though Mookie is already a grown man. It is through interactions like these that Jade is framed merely as an emotional compass and caretaker, left out of important racial discourse that happens in the film. And by doing so, Spike Lee problematically continues the erasure of the experiences of women of color.

This formal treatment of the film’s female characters subtly suggests that only men can participate in social justice conversations, echoing the problematic racial divide in feminist history. Similar to how cisgendered white suffragists fought for voting rights just for themselves, excluding women of color, Lee’s Black female characters’ shallow representation diminishes their voices. He continues this trend with Mother Sister, another character who lacks substance. Throughout the film, Mother Sister is characterized as a voice of reason for the men and nothing more. One of her first lines is telling Mookie not to work too hard, as “it’s gonna be hot as the devil” and she doesn’t want him “falling out from the heat” (10). And when Da Mayor takes a long swig of beer, she criticizes him, asking, “what did I tell ya about drinking in front of my stoop?” (12). In both examples, she exists simply to give advice or to critique the actions of a man. Even her name, “Mother Sister,” is a reflection of how Lee defines her through her relationships with others rather than providing the character with a name of her own, which demonstrates that she is dispensable, a body positioned solely to be an emotional guide and nothing more. Only appearing to either criticize or appraise Da Mayor’s actions, Mother Sister never takes part in the important racial discourse Lee highlights through his male characters. Mother Sister is an accessory in Da Mayor’s world, just like Tina is in Mookie’s.

This formal treatment of the film’s female characters subtly suggests that only men can participate in social justice conversations, echoing the problematic racial divide in feminist history. Similar to how cisgendered white suffragists fought for voting rights just for themselves, excluding women of color, Lee’s Black female characters’ shallow representation diminishes their voices. He continues this trend with Mother Sister, another character who lacks substance. Throughout the film, Mother Sister is characterized as a voice of reason for the men and nothing more. One of her first lines is telling Mookie not to work too hard, as “it’s gonna be hot as the devil” and she doesn’t want him “falling out from the heat” (10). And when Da Mayor takes a long swig of beer, she criticizes him, asking, “what did I tell ya about drinking in front of my stoop?” (12). In both examples, she exists simply to give advice or to critique the actions of a man. Even her name, “Mother Sister,” is a reflection of how Lee defines her through her relationships with others rather than providing the character with a name of her own, which demonstrates that she is dispensable, a body positioned solely to be an emotional guide and nothing more. Only appearing to either criticize or appraise Da Mayor’s actions, Mother Sister never takes part in the important racial discourse Lee highlights through his male characters. Mother Sister is an accessory in Da Mayor’s world, just like Tina is in Mookie’s.

As the mother of his child, Tina spends her scenes reminding Mookie of his fatherly responsibilities. She begs him to “spend some time with [her]…to try and make [their] relationship work” (40). It is through Tina that Lee creates another layer to Mookie’s character, presenting him as an irresponsible father while keeping Tina one-dimensional. When Tina isn’t nagging Mookie about his parental duties, she is displayed as a sexual object. Spike Lee includes a scene where Mookie is rubbing an ice cube all over Tina’s naked body, generous in screen time. There are close ups and long takes; it is a scene clearly produced for the male gaze. By providing very diluted characterizations of Jade, Mother Sister, and Tina, Do the Right Thing flattens the voice of Black women,continuing to erase the complexities and depth Black women have to offer regarding important social justice issues.

As the mother of his child, Tina spends her scenes reminding Mookie of his fatherly responsibilities. She begs him to “spend some time with [her]…to try and make [their] relationship work” (40). It is through Tina that Lee creates another layer to Mookie’s character, presenting him as an irresponsible father while keeping Tina one-dimensional. When Tina isn’t nagging Mookie about his parental duties, she is displayed as a sexual object. Spike Lee includes a scene where Mookie is rubbing an ice cube all over Tina’s naked body, generous in screen time. There are close ups and long takes; it is a scene clearly produced for the male gaze. By providing very diluted characterizations of Jade, Mother Sister, and Tina, Do the Right Thing flattens the voice of Black women,continuing to erase the complexities and depth Black women have to offer regarding important social justice issues.

Through the use of discourse analysis, scholars can dissect how socially produced ideas and objects are both constructed and preserved over time. It offers a method of examining language, visuals, and more, investigating how the way we communicate reveals the construction of our social reality. And since hegemonic ideologies are the governing forces that make up our world, it is critical to examine the ways in which they are represented in the media. Do the Right Thing sparks racial and gendered discourses, shedding light on certain hegemonic ideologies that make up our society. It’s still shockingly relevant despite being a thirty-three year old film, as a piece of media both helpful and harmful. Illustrated through racial tensions in the film, Spike Lee showcases how the possessive investment in whiteness continues to impact communities of color in violent ways. He expresses how whiteness is an unspoken yet frightening force, proven to be both a weapon and a way to pit minority groups against each other. In this way, Do the Right Thing does the important work of examining racial violence. But Do the Right Thing is also flawed, as it perpetuates the exclusion of Black female voices. Lee’s surface-level representations of female characters reflect the racist history of the feminist movement, as well as its sexist origins. Just as the women’s suffrage movement excluded women of color in the fight for voting rights, Lee’s film excludes the opinions of Black women in the conversations about racism. As his Black female characters lack depth and complexity, leaving them out of the film’s anti-racist discourse preserves the hegemonic ideology that women’s experiences aren’t as important as their male counterparts. Overall, Do the Right Thing effectively conveys the power of representation. It emphasizes the violent impacts of a possessive investment in whiteness, while exposing the need for intersectional narratives.

Works Cited

Berger, Arthur. Media Analysis Techniques. Retrieved from

https://usfca.instructure.com/courses/1601815/files/search?preview=68462777&search_term=media+analysis+techniques.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color. Retrieved from https://usfca.instructure.com/courses/1601815/files/search?preview=68462767&search_term=crenshaw. Web.

Lee, Spike. Do the Right Thing. 1 March 1988. Retrieved from https://imsdb.com/scripts/Do-The-Right-Thing.html. Web.

Lipsitz, George. The Possessive Investment in Whiteness. Temple University Press. 10 March 2008, p.1. Retrieved from https://usfca.instructure.com/courses/1601815/files/search?preview=68462768&search_term=lipsitz. Web.

Staples, Brent. “How the Suffrage Movement Betrayed Black Women.” The New York Times, 28 July 2018, p.1-3. Retrieved from https://usfca.instructure.com/courses/1601815/files/search?preview=68462748&search_term=black+women. Web.