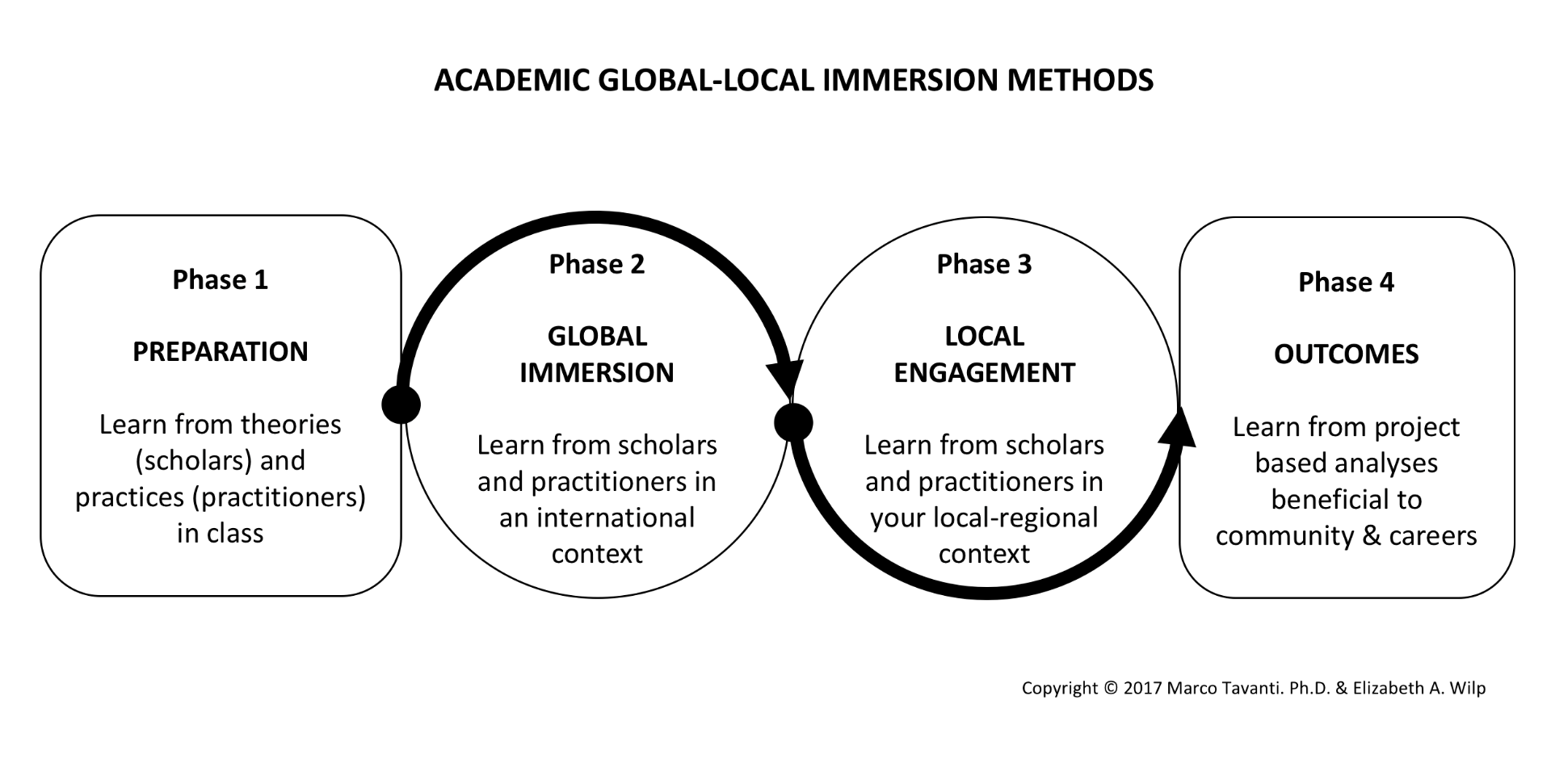

The University of San Francisco’s Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good has been in the forefront of integrating community engagement in higher education. Recently, McCarthy Profiles for Community Engagement Learning included the reflections of Dr. Marco Tavanti on the MNA and now USF offered Academic Global Immersion (AGI-Rome) on Refugee Service Management as an example of experiential learning for global-local engagement (pp. 26-27).

Experiential learning, community engagement and project based education are probably the most important values behind the MNA Program. Our best practices in integrating professional experience and community have been recognized as emerging innovations and effective practices for nonprofit management education (NME), a field pioneered by Dr. Michael O’Neil in the MNA Program and his research.

In the accreditation process with the Nonprofit Academic Center Council (NACC) this feature of the MNA program was recognized as distinction of this degree as a learning beyond the classroom and beyond just service. In an article recently published by Journal of Nonprofit Education and Leadership (JNEL) the advantage and strategic process of of integrating a Nonprofit Management Education (NME) programs like ours into experiential learning is crucial.

Access the entire article here:

This is an excerpt from the Tavanti & Wilp JNEL 2018 article on the integration of Experiential Learning and Community Engagement into Nonprofit Management Education. These reflections and classifications should help Higher Education Institutions to thing strategically on how to integrate High Impact Practices (HIPS) into their curricula and programs.

“Learning through real-world experiences is a valued pedagogy in higher education and an essential method for educating effective nonprofit managers in the 21st century. The practical fields of management education and nonprofit management education (NME) aim to develop appropriate skills, competencies, and mind-sets relevant to administrative, organizational, and leadership careers. These objectives cannot be sufficiently accomplished through in-class lectures and activities only. They require more hands-on and community-centered approaches that increase student exposure to real-world situations while benefiting the capacity development needs of nonprofit organizations (NPOs) and the sector. When the NME field started offering nonprofit-specific graduate programs in the United States with the University of San Francisco’s Master in Nonprofit Organization Management (MPA/NOM in 1983), later renamed Master of Nonprofit Administration (MNA in 1985), the need for experiential learning was not as urgent as today. Most of the students in the early development of the field were professionals with several years of experience in the sector. They sought theories to understand their own practices, along with university recognition for their leadership advancements (O’Neill & Fletcher, 1998; O’Neill & Young, 1988). The priority in these early years involved identifying the proper curriculum content rather than reflecting on the most appropriate pedagogical methods of delivery. In addition, because the students were already bringing their experiences into the classroom reflections and exercises, the need to utilize more community-centered methods was less of a priority. Michael O’Neill, along with Dennis R. Young and other NME pioneers, argued that the field had emerged to prepare those who were currently working in it or were preparing to be leaders and managers of private not-for-profit organizations, while educating public and private sector leaders and managers to interact more effectively with nonprofits (Dobkin Hall, O’Neill, Vinokur-Kaplan, Young, & Lane, 2001). Today, the distinction between very experienced and less experienced professional students is a major characteristic of the student population. This demands more strategic attention about how instructors teach and students learn, while providing more opportunities for university–community partnerships for capacity development. Properly designed experiential education activities, courses, and programs are fundamental for advancing the professional capacity of the sector and its future leaders (Cacciamani, 2017; Fenton & Gallant, 2016).

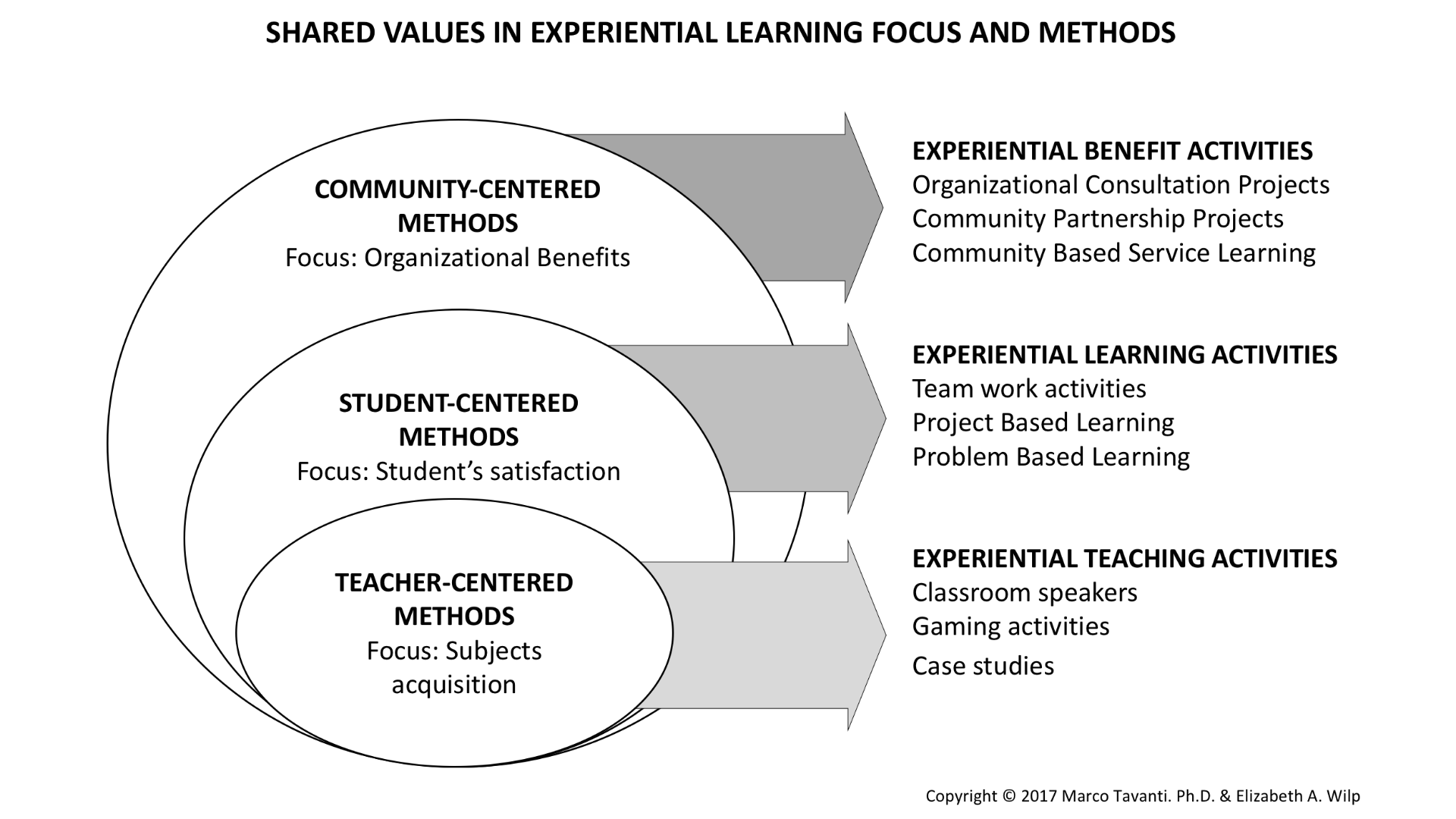

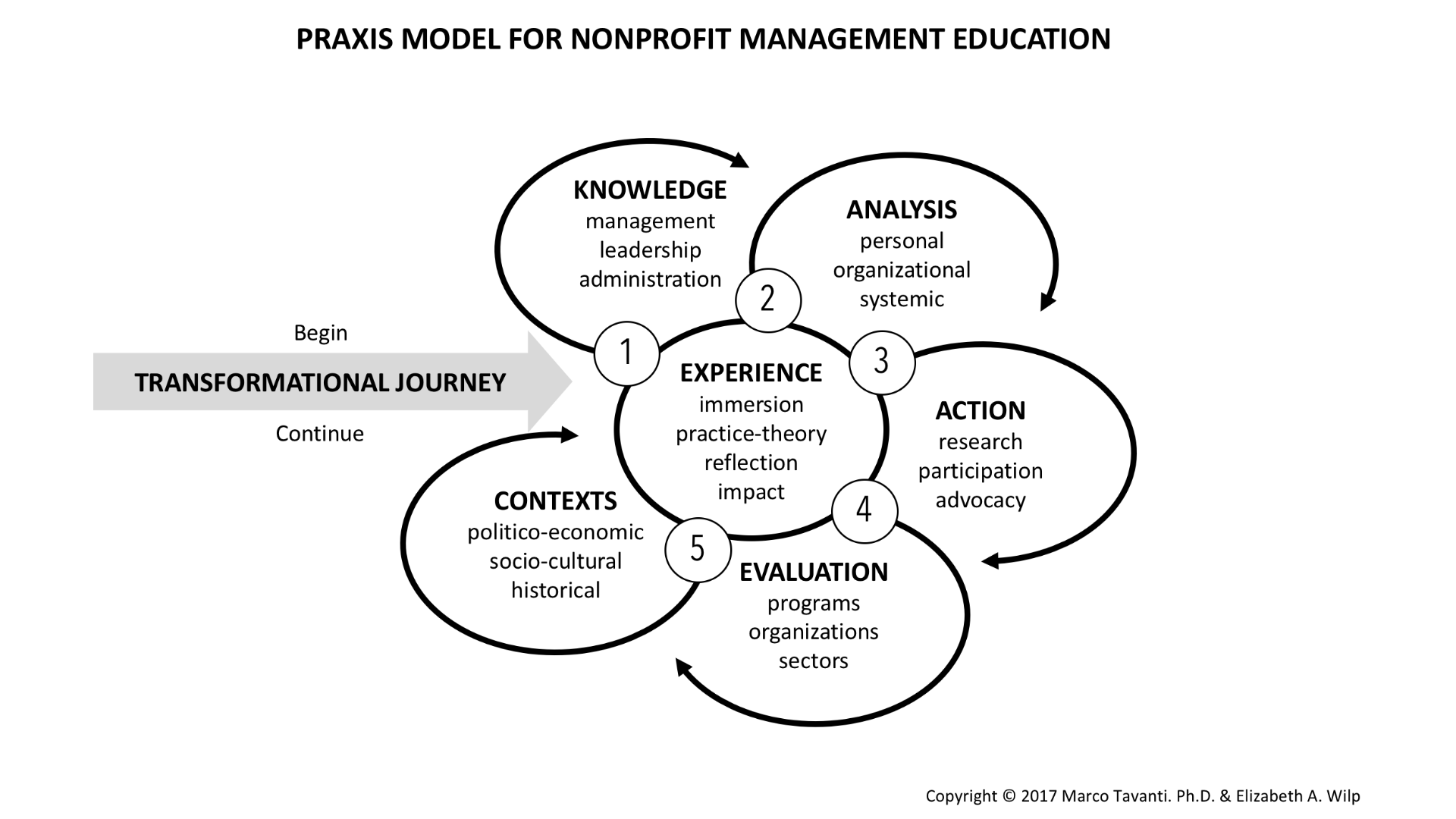

[…] “In graduate NME, experiential learning is and should be more than active learning or service learning. It is about working with NPOs to increase their organizational capacity, while accompanying students to become more effective in their competencies and capacity to consult, assess, and collaborate. The current shifts from experiential learning to experiential education and from service learning to community-engaged learning show the contributions of these models. The strategies and contextualization of the experiences in the University of San Francisco’s MNA Program can be adapted by other institutions and NME programs. They can do this by considering a community-centered model of education (Model 1), by considering a pedagogical praxis of students and community transformation (Model 2), and by designing programs that are relevant to local and global communities (Model 3).”

Model 1

Model 2

Model 3

[…] “Active learning, problem-based learning, project-based learning, service learning, and place-based learning are some of the more well-known methods associated with experiential education (Godfrey, 1999). With the growth of NME programs internationally, there is also a clearer need for educating professionals not only with theoretical, philosophical, and historical notions but also with feasible projects and activities benefiting the learner and the partnering organizations.

Experiential learning is a growing field characterized by specific applied methods, a value-based philosophy, and shared benefits across teaching, learning, and communities. “Experiential education is a philosophy that informs many methodologies in which educators purposefully engage with learners in direct experience and focused reflection in order to increase knowledge, develop skills, clarify values, and develop people’s capacity to contribute to their communities. (Association for Experiential Education, para 4). This definition is not exclusive to formal education, but it is relevant to a general approach to teaching, learning, and engagement. A wide diversity of methods, strategies, and approaches relate to practices of experiential learning across disciplines. However, such a diversity is also a source of confusion in the field.

Wurdinger and Carlson (2010) provide a useful overview of the most effective approaches to experiential learning:

- Active Learning: A group of experiential learning activities associated with classroom strategies such as role playing, simulation, debates, presentations, and case studies.

- Problem–Based Learning: Inquiry-based learning activities through in-depth investigations, self-directed research, and group-work inquiries.

- Project–Based Learning: A type of experiential learning that stimulates students’ interests while developing their project management capacity, technology, and research skills and analytical presentation capacity. It can be individual or group work, teacher directed, student directed, or a combination of the two.

- Service Learning: A well-known approach to teaching and learning that often includes planning (community needs), action (service), and reflection (learning). The emphasis is on learning. It can be student centered or community based.

- Placed-Based Learning: A learning focused on a particular place or context. It is a holistic approach to education that uses the immersion into a context to support the vitality of a community. It can be far (global) or near (local).

Excerpt from:

Tavanti, M. & Wilp, E. A. (2018). Experiential-By-Design: Integrating Experiential Learning Strategies into Nonprofit Management Education. Journal of Nonprofit Education and Leadership (JNEL), Special Issue of the Bi-Annual Nonprofit Academic Center Council Conference, 1-23. ISSN: 2157-0604.

Available full text at the Journal of Nonprofit Education and Leadership (JNEL) https://js.sagamorepub.com/jnel

Learn more about these methods and the impact on the students and our communities here http://agirome.blogspot.com/

Learn more how the MNA Program integrate experiential learning for nonprofit management and leadership education here https://www.usfca.edu/management/graduate-programs/nonprofit-administration

Learn more about how our MNA program students learn through collaborative projects with nonprofit organizations and social enterprises in the Capstone Projects and Practicums for social impact analysis here https://usfblogs.usfca.edu/nonprofit/research/