SNCC Pin, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

We who believe in freedom cannot rest…

The SNCC Legacy Project had originally planned to honor the 60th anniversary of SNCC’s founding in Raleigh in April 2020, but the event had to be rescheduled, because of Covid. The Legacy Project convened the SNCC 60th Anniversary Virtual Conference over three days (October 14-16).

I was blessed to participate — as a witness to history, and the history of present struggles. I remain inspired energized and inspired by the experience, and share my reflections, and some of the takeaway insights and lessons I garnered, in this blog posting.

The marvelous new militancy

The Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-56 demonstrated the power of the organized Black community of Montgomery. The boycott’s successful outcome transformed the city, desegregating public transportation. It was a shot across the bow for the system of white supremacist apartheid throughout the Jim Crow south.

Rosa Parks and Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. had gone from local community leaders to leading figures of a new national civil rights movement. But the Montgomery movement did not transform that system, not outside the boundaries of one Alabama city, nor did it lead to a cascade of other successful desegregation campaigns. Dr. King could not replicate his success in Montgomery — not in 1957, or 1958, or 1959…

In 1960, nonviolent direct action shook the Jim Crow system to its core throughout the former Confederate states. But this transformative direct action was not generated by Dr. King, nor any established civil rights leaders. On the contrary, young people — militant Black college students, and a small number of committed white students who joined them — were the driving force of radical social change.

The sit-in movement initially targeted segregation at lunch counters throughout the south. It started with just four Black students — Joseph McNeil, Ezell Blair, Franklin McCain, and David Richmond — from North Carolina A & T College. On February 1, 1960, these four young men sat down at the Whites Only lunch counter at Woolworths in Greensboro, North Carolina. The returned back the next day — with twenty or so friends. By the end of February, sit-ins had taken place at more than 30 locations in 7 states throughout the South. By the end of April over 50,000 students had participated.

Three years later, Dr. King spoke before the Lincoln Memorial to praise “the marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community.” The primary drivers of this nonviolent militancy were college students and other young activists from the Black communities throughout the South.

Ella Baker understood this earlier, and more clearly, than did King. An intensely dedicated, charismatic leader in the black freedom struggle since the 1940s, Baker was in the process of leaving Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to become, along with Rev. James Lawson and Rev. C.T. Vivian in Nashville, one the most influential mentors to the nascent student movement. King admired and supported the sit-in protestors and Freedom Riders — but there was always some distance between them. In contrast, Rev. Vivian got on the bus with the young students, Lawson trained them in nonviolence, and Baker advised them with fierce, uncompromising encouragement and love.

Ella Baker. The Ella Baker Center for Human Rights. Courtesy of the public domain.

The birth of SNCC

Immediately following the initial wave of sit-ins, Baker engaged in dialogue with hundreds of young activists to support the nascent student movement and she was the leading organizer of the gathering of sit-in leaders and young Black activists from throughout the South that launched the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

In her book Ella Baker & the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (Chapel Hill, 2003), historian Barbara Ransby recalls:

“After the success at Greensboro and the wave of sit-ins that rippled across the South, Baker took immediate steps to help the students consolidate their initial victories and make linkages with one another, and she set the stage to move them in what she hoped would be a leftward direction. Under the auspices fo SCLC, Baker called for a gathering of sit-in leaders to meet one another, assess their respective struggles, and explore the possibilities for future actions.”

The gathering took place April 16-18, 1960, at Shaw University, in Raleigh, North Carolina — Baker’s alma mater. Rev. Lawson brought the important Nashville contingent. Dr. King came to the meeting, joining about 200 young people from across the South.

“For many of the students, it was not until the gathering in Raleigh that they fully appreciated the national significance of their local activities., They felt honored by the presence of Dr. King, whom they had watched on television or read about in the black and mainstream press. He was a hero for most black people in 1960, and his presence gave the neophyte activists a clear sense of their own contribution to the growing civil rights movement. Baker was content to use King’s celebrity to attract young people to the meeting, but she was determined that they take away something more substantial. Most of the student activists had never heard of Ella Baker before they arrived. Yet she, more than King, became the decisive force in their collective political future. It was Baker, not King, who nurtured the student movement and helped to launch a new organization. It was Baker, not King, who offered the sit-in leaders a model of organizing and an approach to politics that they found consistent with their own experience and would find invaluable in the months and years to come.”

As the weekend closed, the students formed a new organization — SNCC. They invited several older leaders to serve as advisers (including Baker and King, and Professor Howard Zinn). For Baker, this involvement became all-consuming, and her impact on young activists like Bob Moses and so many others was immeasurable.

Mississippi SNCC workers at conference at Tougaloo College, 1965. From left to right: Curtis (Hayes) Muhammad, James Jones, Jesse Harris, Wazir (Willie B.) Peacock, Charles McLaurin, Jimmie Travis, Samuel Block, MacArthur Cotton, Hollis Watkins, Dorie Ladner, and Charlie Cobb. James Forman kneels in the foreground. From the Alan Lomax Collection at the Library of Congress. Used courtesy of the Association for Cultural Equity. Photographer unknown.

Remembering SNCC — 60 years later

The 2021 SNCC 60th Anniversary Virtual Conference convened an intensive line up of speakers, conversations, panels and song.

It was an honor to attend as many sessions as I could.

Because many of the sessions were concurrent, it was not possible to attend all of them. But the conference website allowed registered participants to go back and watch videos of sessions they missed, so I have turned to the conference website again and again over the subsequent two weeks to access its archive of powerful strategic discussions.

The SNCC reunion event was a celebration and teach-in. The legacy of SNCC as a transformative organization for social change in the United States was honored, with many veterans of the movement gathering virtually to honor the historical and spiritual power of the movement they led as students six decades ago.

The conference planners worked hard to facilitate a rigorous multigenerational dialogue throughout. United by the conference theme (“Organizing Our Strength For Tomorrow”), remembered the voting rights and human rights struggles in Mississippi, Georgia, Alabama and throughout the Jim Crow south not for purposes of nostalgia, but to garner lessons for the present and future.

In each session, panelists wrestled with an underlying questions of great urgency– how can the Black Freedom Movement of the 1960s inform the Movement for Black Lives today. The goal of each session was to foster strategic mobilization to successfully engage racial justice struggles we face in America today: how do we overcome the renewed backlash of white supremacy, endemic inequality, racist policing, Jim Crow disenfranchisement, voter suppression and voter nullification, and the epidemic of gun violence?

The approach was radical throughout — strategizing about how to address these entrenched problems at the root.

Throughout the conference, you could feel the living spirit of Ella Baker, Julian Bond, Fannie Lou Hamer, John Lewis, Bob Moses and so many other SNCC heroes who fought to make our country more just, democratic and free.

Among the standout moments

For everyone who could not be with us, I would like to share with you some highlight moments from a few of the extraordinary conference sessions, including sons and daughters of SNCC leaders of the 1960s, carrying forward their legacy of activism.

I attended several sessions addressing criminal justice reform and the Black community, including an amazing conversation between Yale Law Professor James Forman, Jr. (son of James Forman the militant Black Freedom Movement activist who became SNCC Executive Secretary) and Keith Ellison, Keith Ellison, Attorney General of Minnesota (following year serving Minnesota’s 5th Congressional District in the U.S. House of Representatives), who discussed strategies to address racist disparities in criminal justice at the state, county and municipal levels.

We who believe in freedom cannot rest…

Until the killing of black men, black mother’s sons

Is as important as the killing of white men, white mother’s sons

I savored the opportunity to hear stories, reflections and strategic lessons from SNCC veterans like Freddie Biddle, Courtland Cox, Jennifer Lawson, Charles McLaurin, Judy Richardson, and Hollis Watkins — and to sing with the SNCC Freedom Singers who are still around to bring the spirit down to awaken our souls through the living songs of the movement.

And I was impressed by so many young activists who are carrying on the struggle, including Nse Ufot, who leads the New Georgia Project (which has registered over 500,000 Georgians to vote), young Black history scholars Hasan Kwame Jeffries (Ohio State) and Imani Perry (Princeton), and Maisha Moses, Executive Director of The Young People’s Project, who fights to broaden access by underrepresented groups to high quality education in science, mathematics, engineering, and technology, and who beautifully carries forward the fierce commitment to education as a human right, upon which democracy depends, as her father Bob Moses exemplified throughout his life.

Black farmers and community land trusts

Leah Penniman, left, tends the crops at Soul Fire Farm. Courtesy of Soul Fire Farm

1) Coming Together (“In the first stage, young civil rights activists came together in SNCC to form a community within a social struggle… Viewed as the ‘shock troops’ of the civil rights movement, SNCC activists established projects in such areas as rural Mississippi considered too dangerous by other organizations…. In the summer of 1964 SNCC’s singular qualities cam to national attention when it played a leading role in bringing hundreds of northern students to Mississippi, the main bastion of southern segregation, for a decisive battle over the rights of blacks to vote.”

2) Looking Inward (“The second stage of SNCC’s development began after the defeat of an attempt by the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party [MFDP] to unseat the regular all-white delegation to the Democratic National Convention in August 1964… Over the next two years they looked inward..” Pursuant to this internal process, “They also questioned whether their remaining goals could best be achieved through continued confrontation with existing institutions or through the building of alternative institutions controlled by the poor and powerless.”

3) Falling Apart (“The third phase of SNCC’s development involved the member’s efforts to resolve their differences by calling for black power and black consciousness, by excluding white activists from SNCC, and by building black-controlled institutions. After his election as chairman of SNCC in May 1966, Stokely Carmichael popularized the organization’s new separatist orientation, but he and other workers were unable to formulate a set of ideas that could unify black people… Weakened by internal dissension, SNCC withered in the face of the same tactics of subtle cooptation and ruthless repression that stifled the entire black struggle.”

The SNCC 60th anniversary conference engaged issues and themes that reflected each of these three stages of the organization’s history. But the SNCC Legacy Project had no interest to engage in an autopsy, to rekindle old debates what members could have or should have done more than a half-century ago. Even as the event created a reunion for old friends, the conference planners had a far more ambitious goal than to convene a trip down memory lane for aging SNCC activists.

It was a galvanizing convening of activists for racial justice and Black empowerment across generations. The central question of the conference was the same question that Dr. King left us with in his last book: Where do we go from here: chaos or community?

The driving force of the conference was the power of organized intergenerational action for racial justice, freedom and equality in the United States today and going forward into the future.

Black power — not as a slogan, or stance of rhetorical defiance. Black power as the realization of community over chaos, food sovereignty over scarcity, voter registration over disenfranchisement, electoral office over disengagement, solidarity over nihilism, cohesion over division, organized nonviolence over systemic violence, the empowerment of grassroots Black leadership.

Concluding reflections

Barbara Ransby recounts an especially turbulent and divisive SNCC meeting held in August 1961 at the iconic Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, during which SNCC almost broke up.

“Bob Moses had come to the conclusion that the disenfranchisement of poor southern blacks was the cutting-edge issue the movement needed to address. He was not so naive as to think that voting would solve all the problems African Americans faced, but he did become convinced, strongly influenced by [long-time Mississippi voter registration activist] Amzie Moore, that their oppression hinged in part on their total political powerlessness. Moses could not attend the Highlander meeting, but Charles McDew, Charles Sherrod [future husband of Shirley Sherrod], and Charles Jones were in favor of the voter registration project and argued for that position in the meeting. In contrast, Diane Nash and many of the Nashville activists had retained an almost spiritual investment in the tactic of nonviolent direct action…. Passions were heated; tensions were high; and some of the participants felt that the only way both factions could remain true to their convictions was to part ways.”

Ella Baker stood in the way.

“And it was her aggressive intervention that calmed the situation, abated the rancor, and preserved unity. ‘I opposed the split as serving the purposes of the enemy,’ she recalled years later…. She stood up and spoke forcefully in the meeting, calling for the formation of two wings of one organization. Rather than two organizations, one wing would focus on direct action and other other on voter education and registration,” the path the activists followed.

This spirit of inclusion, unity, reconciliation and cohesion at the service of united, strategic, fusion of community organizing and nonviolent direct action — the spirit of Ella Baker — permeated the SNCC 60th anniversary conference.

“Dig into and embed yourself in a black community… make your way toward a community consensus, figure out what the people are prepared to do, what they will fight for… discover strength you never knew was there… earn the people’s trust (we earned it by sitting on front porches, going to church, beer at the juke joint, playing basketball with young guys), until the people can come to the point where they feel they can take a chance with you… and remember Fannie Lou Hamer, forced to drop out of school when she was 12 years old, who said ‘if I can do it, you can do it…’ Start right in your own neighborhood, talk to people in your own community, combine direct action protest and community organizing…“

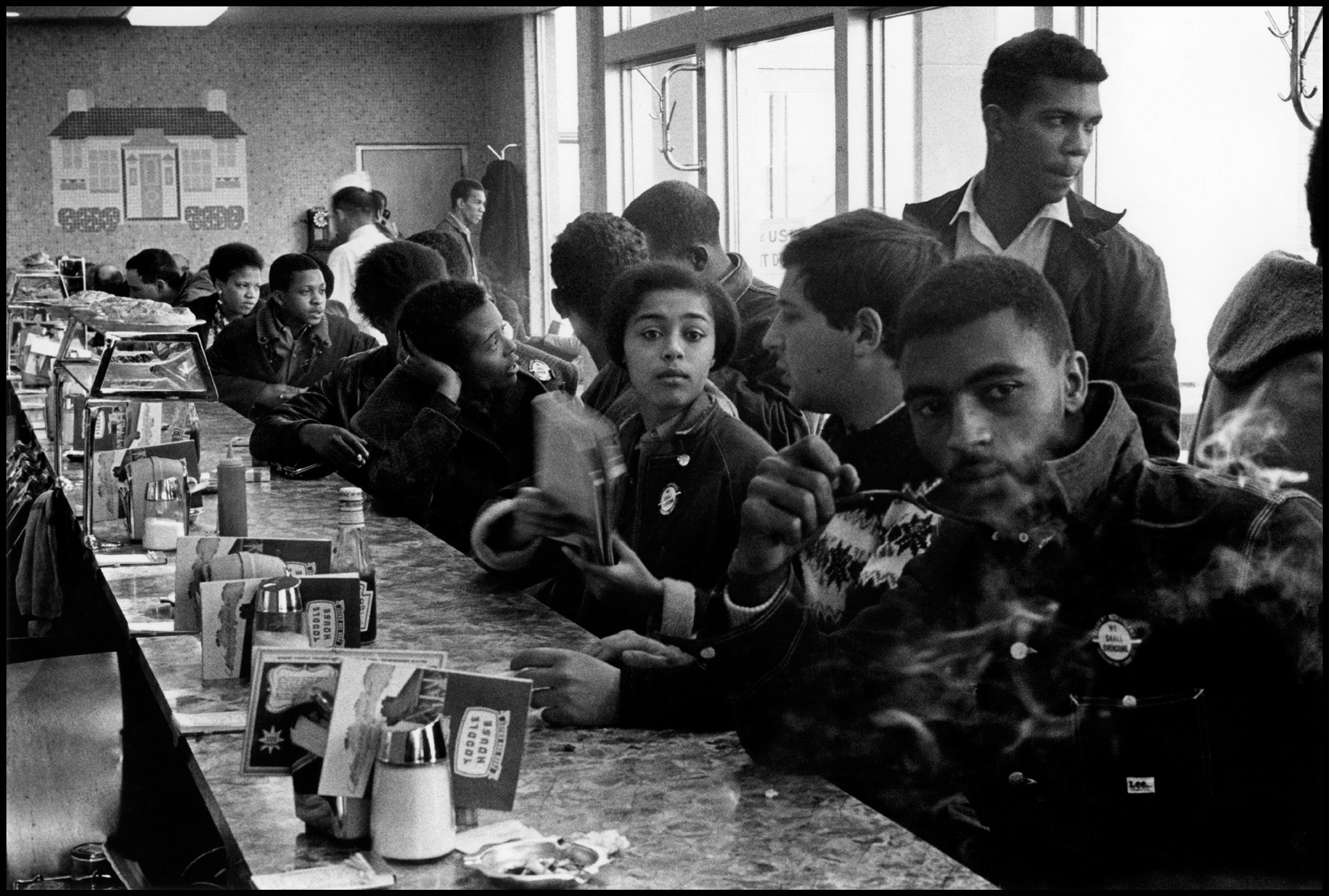

Atlanta, Georgia sit-in with Taylor Washington, Ivanhoe Donaldson, Joyce Ladner, John Lewis, Judy Richardson, George Green, and Chico Neblett. 1964.

Source: Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos. Courtesy of the Zinn Education Project.

Further reading

If you are interested to read more about SNCC, its history and impact, and the stories of some of its most important members, I recommend the following:

Eric Burner, And Gently He Shall Lead Them: Robert Parris Moses and Civil Rights in Mississippi (NYU Press, 1994)

Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (Harvard, 1981, 1995).