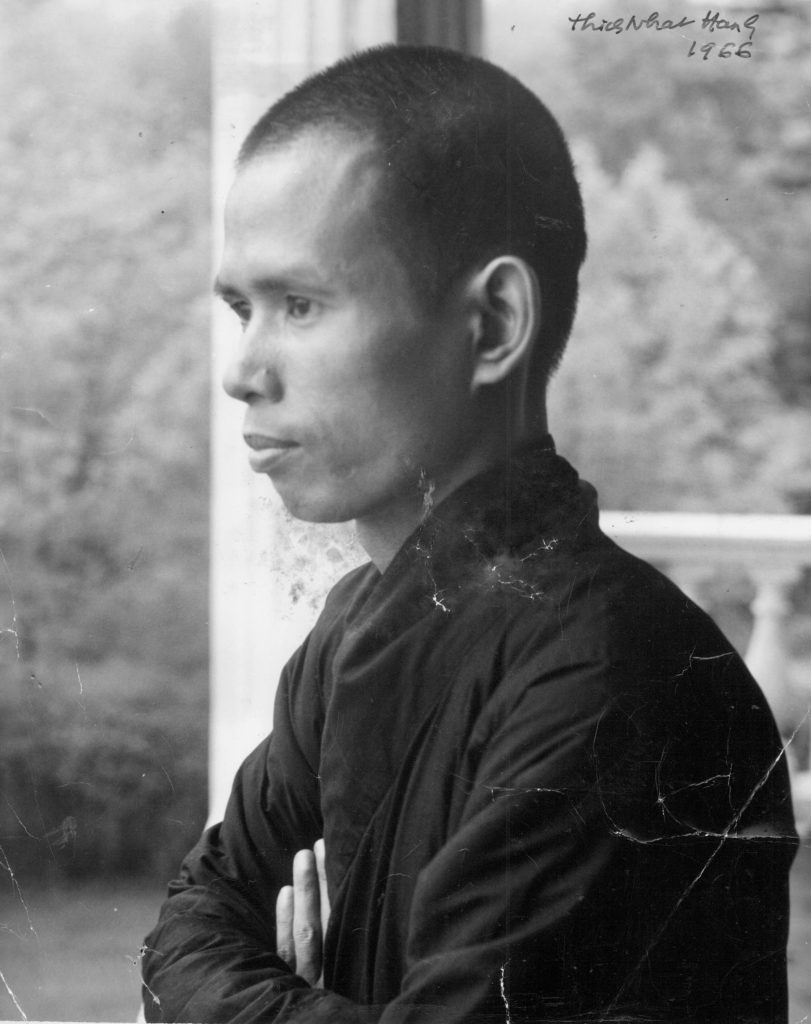

Thich Nhat Hanh, Photo from Plum Village

This is dedicated to the life, teachings and living spirit of Thich Nhat Hanh, known by his followers as Thay, who passed away last week at Từ Hiếu Temple in Huế, Vietnam, at the age of 95.

Thay’s role in the global histories of Buddhism and nonviolence is immense. Perhaps more than any other figure, he brought mindfulness to modern societies all over the world, and he expanded his own faith to empower new forms of “Engaged Buddhism” to oppose war, injustice, cruelty and oppression.

Click here for a full 20-page biography of Thay’s life, published by The International Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism (Plum Village), the practice community in France he founded.

In a moving statement, addressed “Dear Beloved Community” the monks and nuns of Plum Village announced Thay’s death:

Thay has been the most extraordinary teacher, whose peace, tender compassion, and bright wisdom has touched the lives of millions. Whether we have encountered him on retreats, at public talks, or through his books and online teachings–or simply through the story of his incredible life–we can see that Thay has been a true bodhisattva, an immense force for peace and healing in the world. Thay has been a revolutionary, a renewer of Buddhism, never diluting and always digging deep into the roots of Buddhism to bring out its authentic radiance.

Plum Village will offer a series of memorial services and ceremonies throughout the coming week (each day, through January 29) that will be livestreamed for everyone. If you are interested to virtually attend any of these services or ceremonies, you can do so here.

Thich Nhat Hanh with young monks at Plum Village. Photo from Plum Village

Thich Nhat Hanh has deeply informed the work of the USF Institute for Nonviolence and Social Justice, and he has been an important presence in this Fierce Urgency blog.

Click here for a brief discussion of Thay’s dedication to peace and nonviolence, and his impact on our world.

Click here for a brief account of Thay’s profound relationship with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr..

Thay was as a prophet of nonviolence throughout his lifetime. In this brief essay, I focus on his opposition to the war in his native country, his impact on Martin Luther King, Jr., and their collaborative effort to oppose the Vietnam War through what Gandhi called satyagraha — soul force — the power of truth and love. I draw from a variety of sources, the full biography of Thich Nhat Hanh published by the Plum Village community, and the marvelous new book by the Rt. Rev Dr. Marc Handly Andrus, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of California, Brothers in the Beloved Community: The Friendship of Thich Nhat Hanh and Martin Luther King, Jr. (Parallax Press, 2021), Thay’s books, and primary source material (letters from Thich Nhat Hanh and Martin Luther King, Jr.).

On suffering and nonviolent resistance to evil

In a passage in his memoir Fragrant Palm Leaves (1999), Thay describes a spiritual breakthrough he experienced in late 1962 after contemplating the writings of the German pastor and theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer. With immense moral and personal courage, Bonhoeffer had actively opposed the Nazi regime, leading to his imprisonment and execution. Bonhoeffer had the opportunity to leave Germany for safe refuge in the United States, but he declined. “I will have no right to participate in the reconstruction of Christian life in Germany after the war if I do not share the trials of this time with my people,” he wrote). Bonhoeffer also criticized his fellow Christian clergy: “the Church was silent when it should have cried out, because the blood of the innocent was crying aloud to heaven.” Quoted in Franklin Sherman, “Dietrich Bonhoeffer,” in Encyclopaedia Britannica (2019).

Reading Bonhoeffer, Thay had a spiritual epiphany on the night of November 2, 1962, while teaching in the United States. Contemplating Bonhoeffer’s response to Hitler’s Third Reich, and the pastor’s final days in a Nazi prison cell awaiting execution, Thay experienced a powerful “surge of joy”:

..I was awakened to the starry sky that dwells in each of us. I felt a surge of joy, accompanied by the faith that I could endure even greater suffering than I had thought possible. Bonhoeffer was the drop that made my cup overflow, the last link in a long chain, the breeze that nudged the ripened fruit to fall. After experiencing such a night, I will never complain about life again. […] All feelings, passions, and sufferings revealed themselves as wonders, yet I remained grounded in my body. Some people might call such an experience ‘religious,’ but what I felt was totally and utterly human. I knew in that moment that there was no enlightenment outside of my own mind and the cells of my body. Life is miraculous, even in its suffering. Without suffering, life would not be possible.

Nhat Hanh, Fragrant Palm Leaves (1999), p.85

Memorial to Rev. Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Wikimedia Commons.

Living Nonviolence: leadership of the Buddhist movement for peace in Vietnam

Returning to Vietnam in January 1964, Thay became a leader of an emerging movement for peace, social action, humanitarian service, rural development and poverty alleviation among his fellow Buddhist monks and nuns who came together in a Unified Buddhist Congregation. As the war escalated, Thay called for cessation of hostilities, and the commencement of peace talks between North and South.

Thay was a poet as well as a monk. Here is an excerpt from “Condemnation,” a poem he wrote in 1964, published in a Vietnamese Buddhist magazine:

Whoever is listening, be my witness:

I cannot accept this war.

I never could I never will.

I must say this a thousand times before I am killed.

I am like the bird who dies for the sake of its mate,

dripping blood from its broken beak and crying out:

“Beware! Turn around and face your real enemies

— ambition, violence hatred and greed.

As he became more outspoken against the war, Thay was denounced by the South Vietnamese government as a pro-Communist propagandist. This did not deter him from speaking out against the war, and organizing thousands of student volunteers for the School of Youth for Social Service, a politically-neutral grassroots relief organization providing humanitarian aid to bombed villages and undeveloped communities.

Thich Nhat Hanh, 1966; from the Plum Village website

In February 1966 Thầy established the Order of Interbeing, a new Buddhist movement emphasizing Thay’s teaching of “not taking sides in a conflict” as a form of nonviolent resistance, “a direct answer to war, a direct answer to dogmatism, where everyone is ready to kill and die for their beliefs.”

“The Vietnam War was, first and foremost, an ideological struggle. To ensure our people’s survival, we had to overcome both communist and anticommunist fanaticism, and maintain the strictest neutrality. Buddhists tried their best to speak for all the people and not take sides, but we were condemned as ‘pro-communist neutralists.’ Both warring parties claimed to speak for what the people really wanted, but the North Vietnamese spoke for the communist bloc and the South Vietnamese spoke for the capitalist bloc. The Buddhists only wanted to create a vehicle for the people to be heard—and the people only wanted peace, not a “victory” by either side. But the sound of the planes and bombs was too loud. The people of the world could not hear us. So I decided to go to America and call for a cessation of the violence.”

Meeting Martin Luther King, Jr.

I highly recommend marvelous Bishop Marc Andrus’s new book, Brothers in the Beloved Community: The Friendship of Thich Nhat Hanh and Martin Luther King, Jr. (Parallax Press, 2021), a deeply insightful meditation on the idea of Beloved Community as expressed and exemplified in Thay’s relationship with Dr. King, and the transformative impact each man had on the other, and on our world.

Thay wrote to Dr. King from Vietnam in June 1956. Because letter is so profound, and because it powerfully affected Dr. King, I attach it in full below.

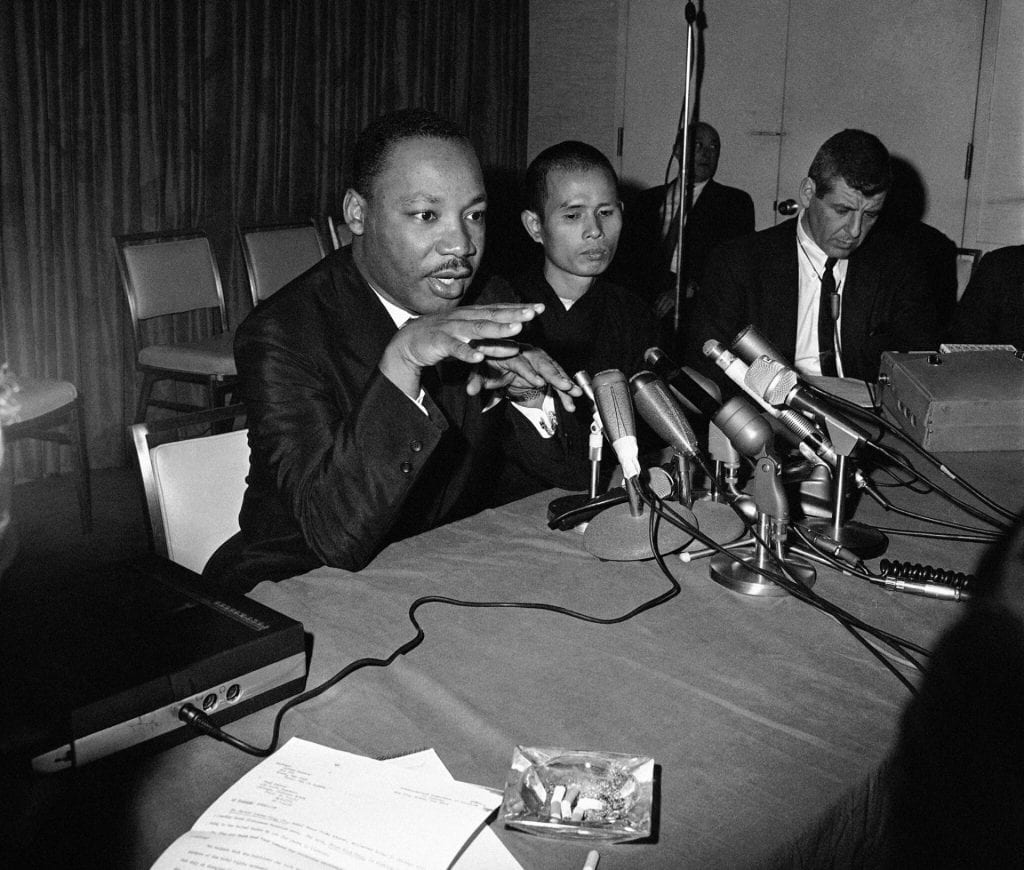

Thay and Dr. King finally met on May 31st, 1966. Their joint press conference in Chicago at the Sheraton Hotel was one of the first occasions Dr. King spoke out publicly against the war in Vietnam. In a powerful joint statement, they compared the civil rights protestors and the Buddhist monks and nuns who set themselves fire in Vietnam to protest the war:

“We believe that the Buddhists who have sacrificed themselves, like the martyrs of the civil rights movement, do not aim at the injury of the oppressors, but only at changing their policies. The enemies of those struggling for freedom and democracy are not men. They are discrimination, dictatorship, greed, hatred and violence, which lie within the hearts of man. These are the real enemies of man—not man himself.

We also believe that the struggle for equality and freedom in Birmingham, Selma and Chicago, as in Hue, Danang and Saigon, are aimed not at the domination of one people by another. They are aimed at self-determination, peaceful social change, and a better life for all human beings. And we believe that only in a world of peace can the work of construction, of building good societies everywhere, go forward.

We join in the plea, written June 1, 1965, bu Thich Nhat Hanh in a letter to Martin Luther King, Jr., “Do not kill man, even in man’s name. Please kill the real enemies of man which are present everywhere, in our very hearts and minds.”

Thich Nhat Hanh and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. & Thích Nhất Hạnh, Chicago 31-5-1966; Edward Kitch | Credit: AP; Creative Commons

In January 1967, six months after they first met, Dr. King nominated Thầy for the Nobel Peace Prize. I also attach this important letter below. Marc Andrus suggests that Dr. King wrote the letter, and made it public as an act of nonviolence, to create pressure on the Nobel Committee to oppose the Vietnam War. (1967 was one of the few years when the Nobel Committee made no award for the Nobel Peace Prize.).

On April 4, 1967, Dr. King delivered his “Beyond Vietnam” speech at the Riverside Church in New York, in which he delivered his most powerful denunciation of the Vietnam War, a speech that was bitterly criticized not only by conservatives but also from African American civil rights leaders. In this iconic speech, Dr. King quoted from Thay: “Men are not our enemy. Our enemy is hatred, discrimination, fanaticism and violence.”

The following month, in May 1967, Dr. King and Thay met in Geneva for a second and final time, at a conference of the World Council of Churches. Thay describes describes a breakfast they enjoyed together.

“We were able to continue our discussion on peace, freedom, and community, and what kind of steps America could take to end the war. And we agreed that without a community, we cannot go very far. Without a happy, harmonious community, we will not be able to realize our dreams.

I said to him, ‘Martin, do you know something? In Vietnam, they call you a bodhisattva, an enlightened being trying to awaken other living beings and help them move toward more compassion and understanding.’ I’m glad I had the chance to tell him that, because a few months later he was assassinated in Memphis.

Their discussions centered in particular on their shared global vision of a ‘beloved community,’ a fellowship among peoples and nations built on principles of nonviolence, reconciliation, justice, tolerance, and inclusiveness in which even enemies can become friends. Theirs was not a utopian vision, but a realistic, achievable goal attained when a critical mass of people can be trained in the principles and practices of peace and nonviolence.

Less than a year later Dr. King was assassinated. Thầy was in the U.S. when he heard the tragic news. Their friendship, shared courage and vision, and then the loss, had a profound impact on him. “I was devastated,” he later said. “I could not eat. I could not sleep. I made a deep vow to continue building what he called ‘the beloved community,’ not only for myself but for him also. I have done what I promised to Martin Luther King, Jr. And I think that I have always felt his support.

In his most recent book, Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet, published just a few months ago, Thay at 95 reiterated his commitment to nonviolence as our “North Star.”

“Our enemy is not other people,” he pleads. “Our enemy is hatred, violence, discrimination, and fear.”

“It is possible to respond to hate with love,” Thay reminds us, echoing Dr. King. “It is possible to respond to violence with compassion and non-violent action.”

Photo from Plum Village

Letter from Thich Nhat Hanh to Martin Luther King, Jr., June 1965

The self-burning of Vietnamese Buddhist monks in 1963 is somehow difficult for the Western Christian conscience to understand. The Press spoke then of suicide, but in the essence, it is not. It is not even a protest. What the monks said in the letters they left before burning themselves aimed only at alarming, at moving the hearts of the oppressors and at calling the attention of the world to the suffering endured then by the Vietnamese. To burn oneself by fire is to prove that what one is saying is of the utmost importance. There is nothing more painful than burning oneself. To say something while experiencing this kind of pain is to say it with the utmost of courage, frankness, determination and sincerity. During the ceremony of ordination, as practiced in the Mahayana tradition, the monk-candidate is required to burn one, or more, small spots on his body in taking the vow to observe the 250 rules of a bhikshu, to live the life of a monk, to attain enlightenment and to devote his life to the salvation of all beings. One can, of course, say these things while sitting in a comfortable armchair; but when the words are uttered while kneeling before the community of sangha and experiencing this kind of pain, they will express all the seriousness of one’s heart and mind, and carry much greater weight.

The Vietnamese monk, by burning himself, say with all his strengh [sic] and determination that he can endure the greatest of sufferings to protect his people. But why does he have to burn himself to death? The difference between burning oneself and burning oneself to death is only a difference in degree, not in nature. A man who burns himself too much must die. The importance is not to take one’s life, but to burn. What he really aims at is the expression of his will and determination, not death. In the Buddhist belief, life is not confined to a period of 60 or 80 or 100 years: life is eternal. Life is not confined to this body: life is universal. To express will by burning oneself, therefore, is not to commit an act of destruction but to perform an act of construction, i.e., to suffer and to die for the sake of one’s people. This is not suicide. Suicide is an act of self-destruction, having as causes the following:

- lack of courage to live and to cope with difficulties

- defeat by life and loss of all hope

- desire for non-existence (abhava)

This self-destruction is considered by Buddhism as one of the most serious crimes. The monk who burns himself has lost neither courage nor hope; nor does he desire non-existence. On the contrary, he is very courageous and hopeful and aspires for something good in the future. He does not think that he is destroying himself; he believes in the good fruition of his act of self-sacrifice for the sake of others. Like the Buddha in one of his former lives — as told in a story of Jataka — who gave himself to a hungry lion which was about to devour her own cubs, the monk believes he is practicing the doctrine of highest compassion by sacrificing himself in order to call the attention of, and to seek help from, the people of the world.

I believe with all my heart that the monks who burned themselves did not aim at the death of the oppressors but only at a change in their policy. Their enemies are not man. They are intolerance, fanaticism, dictatorship, cupidity, hatred and discrimination which lie within the heart of man. I also believe with all my being that the struggle for equality and freedom you lead in Birmingham, Alabama… is not aimed at the whites but only at intolerance, hatred and discrimination. These are real enemies of man — not man himself. In our unfortunate father land we are trying to yield desperately: do not kill man, even in man’s name. Please kill the real enemies of man which are present everywhere, in our very hearts and minds.

Now in the confrontation of the big powers occurring in our country, hundreds and perhaps thousands of Vietnamese peasants and children lose their lives every day, and our land is unmercifully and tragically torn by a war which is already twenty years old. I am sure that since you have been engaged in one of the hardest struggles for equality and human rights, you are among those who understand fully, and who share with all their hearts, the indescribable suffering of the Vietnamese people. The world’s greatest humanists would not remain silent. You yourself can not remain silent. America is said to have a strong religious foundation and spiritual leaders would not allow American political and economic doctrines to be deprived of the spiritual element. You cannot be silent since you have already been in action and you are in action because, in you, God is in action, too — to use Karl Barth’s expression. And Albert Schweitzer, with his stress on the reverence for life and Paul Tillich with his courage to be, and thus, to love. And Niebuhr. And Mackay. And Fletcher. And Donald Harrington. All these religious humanists, and many more, are not going to favour the existence of a shame such as the one mankind has to endure in Vietnam. Recently a young Buddhist monk named Thich Giac Thanh burned himself [April 20, 1965, in Saigon] to call the attention of the world to the suffering endured by the Vietnamese, the suffering caused by this unnecessary war — and you know that war is never necessary. Another young Buddhist, a nun named Hue Thien was about to sacrifice herself in the same way and with the same intent, but her will was not fulfilled because she did not have the time to strike a match before people saw and interfered. Nobody here wants the war. What is the war for, then? And whose is the war?

Yesterday in a class meeting, a student of mine prayed: “Lord Buddha, help us to be alert to realize that we are not victims of each other. We are victims of our own ignorance and the ignorance of others. Help us to avoid engaging ourselves more in mutual slaughter because of the will of others to power and to predominance.” In writing to you, as a Buddhist, I profess my faith in Love, in Communion and in the World’s Humanists whose thoughts and attitude should be the guide for all human kind in finding who is the real enemy of Man.

June 1, 1965

NHAT HANH

Thich Nhat Nanh. “In Search of the Enemy of Man (addressed to (the Rev.) Martin Luther King).” In Nhat Nanh, Ho Huu Tuong, Tam Ich, Bui Giang, Pham Cong Thien. Dialogue. Saigon: La Boi, 1965. P. 11-20.

Martin Luther King Jr. & Thích Nhất Hạnh, Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation, https://thichnhathanhfoundation.org

Letter from Martin Luther King, Jr. to the Nobel Institute January 1967

January 25, 1967

The Nobel Institute

Drammesnsveien 19

Oslo, NORWAYGentlemen:

As the Nobel Peace Prize Laureate of 1964, I now have the pleasure of proposing to you the name of Thich Nhat Hanh for that award in 1967.

I do not personally know of anyone more worthy of the Nobel Peace Prize than this gentle Buddhist monk from Vietnam.

This would be a notably auspicious year for you to bestow your Prize on the Venerable Nhat Hanh. Here is an apostle of peace and non-violence, cruelly separated from his own people while they are oppressed by a vicious war which has grown to threaten the sanity and security of the entire world.

Because no honor is more respected than the Nobel Peace Prize, conferring the Prize on Nhat Hanh would itself be a most generous act of peace. It would remind all nations that men of good will stand ready to lead warring elements out of an abyss of hatred and destruction. It would re-awaken men to the teaching of beauty and love found in peace. It would help to revive hopes for a new order of justice and harmony.

I know Thich Nhat Hanh, and am privileged to call him my friend. Let me share with you some things I know about him. You will find in this single human being an awesome range of abilities and interests.

He is a holy man, for he is humble and devout. He is a scholar of immense intellectual capacity. The author of ten published volumes, he is also a poet of superb clarity and human compassion. His academic discipline is the Philosophy of Religion, of which he is Professor at Van Hanh, the Buddhist University he helped found in Saigon. He directs the Institute for Social Studies at this University. This amazing man also is editor of Thien My, an influential Buddhist weekly publication. And he is Director of Youth for Social Service, a Vietnamese institution which trains young people for the peaceable rehabilitation of their country.

Thich Nhat Hanh today is virtually homeless and stateless. If he were to return to Vietnam, which he passionately wishes to do, his life would be in great peril. He is the victim of a particularly brutal exile because he proposes to carry his advocacy of peace to his own people. What a tragic commentary this is on the existing situation in Vietnam and those who perpetuate it.

The history of Vietnam is filled with chapters of exploitation by outside powers and corrupted men of wealth, until even now the Vietnamese are harshly ruled, ill-fed, poorly housed, and burdened by all the hardships and terrors of modern warfare.

Thich Nhat Hanh offers a way out of this nightmare, a solution acceptable to rational leaders. He has traveled the world, counseling statesmen, religious leaders, scholars and writers, and enlisting their support. His ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity.

I respectfully recommend to you that you invest his cause with the acknowledged grandeur of the Nobel Peace Prize of 1967. Thich Nhat Hanh would bear this honor with grace and humility.

Sincerely,

Martin Luther King, Jr.