The annual Andrew Goodwin Popular Culture Award and Lecture Series is held in honor of former USF Media Studies professor Andrew Goodwin, one of the founding members of the Media Studies Department. He was an influential scholar of popular music, a blogger (“the professor of pop”) and author of the 1992 book Dancing in the Distraction Factory: Music Television and Popular Culture. As a graduate of the famous Birmingham University Center for Cultural Studies, Goodwin was an advocate for and a lover of popular culture and especially, popular music. Each year an award in Goodwin’s honor is given to a junior or senior undergraduate recognizing excellent analysis of popular culture.

Media Studies/Performing Arts and Social Justice junior, Megan Robertson, received the 2023 award for this essay, which was produced in the Fall 2022 session of Media Theory and Criticism at USF, and includes a brief update written in April 2023.

Photo of Karl Marx. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In political economic approaches to media, materialist production determines culture. Culture then is reflected through media – through our movies, newspapers, television programming, radio shows, and through our social media applications, which are reaching more people than ever before. In this paper, I will apply a political economic analysis to the most downloaded iPhone social media application of the past year: TikTok (Chan, 2021, Table 2).

This analysis is based on the theory of 19th-century German philosopher Karl Marx, whose foundational work outlined the ways societies own, organize, and produce capital (McLellan, 2022). This economic base of society determines its cultural values. Along with collaborator Friedrich Engels, Marx claimed:

“The class which is the ruling material force of society is at the same time its ruling intellectual force. The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, consequently also controls the means of mental production, so that the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are on the whole subject to it,” (Durham, M. G., & Kellner, D. M., 2013, p. 31).

Thus, culture is produced by the leading intellectual force, which is the ruling force. This notion can be seen throughout history, from feudal lords in western Europe during the early Middle Ages, to the creation of a merchant class in the late 18th-century industrialization period, and in today’s postmodern society with its global, technology-based economy. In each of these scenarios, Marx’s formation of culture can be seen at work. Whether it be a feudal lord or the CEO of a multi-million dollar tech company, the ideas of the dominant class became the ruling cultural ideas.

This paper uses Marxist selections featured in Arthur Asa Burger’s Media Analysis Techniques. In his discussion of Marx, the professor and media theorist argues:

“Beneath the superficial randomness of things there is a kind of inner logic at work. Everything is shaped, ultimately, by the economic system of a society, which in subtle ways, affects the ideas that individuals have, ideas that are instrumental in determining the kinds of arrangements people will make with one another, the institutions they will establish, and so on” (Berger, 2019, p. 56).

Berger’s claim is based on Marx’s “Base/Superstructure Model.” In this theory, economics forms the base of our society.

It is important to note that as this paper is being written in the United States in 2022, it will commonly refer to capitalism as its foundational materialistic basis, since capitalism happens to be the ruling economic standard in this location and epoch. If this paper were written in another locale, this might not necessarily be the case.

Capitalism is the base of the current society in the U.S. The vast majority of the population was born into this pre-existing economic system. As such, the ways people choose to live their lives directly correlates with the fact that they exist in a system wherein they must work to acquire the necessities for existence, such as nourishment, clothing, and housing. In this way, “capitalism is not only an economic system, but also something that affects attitudes, values, personality types, and culture in general,”(Berger, 2019, p. 58).

Marx refers to the ideological aspects of life that economic systems affect as ‘superstructure.’ These are the institutions and values of society (Berger, 2019, p. 58), the cultural byproducts of those existing in our economic systems. Our culture is directly determined by our economic and political structure.

This notion can likewise be applied to media. Nearly 5 billion people worldwide have social media accounts. Of these social networking platforms, one is being adopted at an astonishingly rapid rate. The short-form video application TikTok has seen a 105% user increase over the past two years in the United States alone (Ruby, 2023).

This paper argues that through corporate sponsoring of TikTok ‘influencers,’ the capitalistic ‘base’ of our society has altered the ‘superstructure,’ changing cultural facets of what to consume, how to present one’s identity to the world, and what to believe, primarily in Gen Z users, aged 11 to 28. Using TikTok as an agent for global change, corporations produce a culture that serves their interests.

The majority of popular social media platforms in the United States, applications like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, were developed in the United States. Chinese-based TikTok is a unique outlier. It was established as an entity in 2018, combining two short form video platforms: Musical.ly and Douyin (Tidy, J., & Smith, S.,2020). Musical.ly was launched in Taiwan in 2014 as a social media application created for users to dance and lip-sync to popular songs. Although it was an app developed in Asia, it enjoyed immense popularity in the United States and Western Europe. At the height of its usage, Musical.ly was one of the best performing apps on the Apple App store with 70 million accounts created at its peak (Carson, 2016).

At the same time, another social media application, Douyin, was a sensation among young users in China (Citizen Lab, 2021). Douyin is comparable to what we know today as TikTok. The platform has a seemingly endless reservoir of user-generated videos, the vast majority of which run less than 60 seconds. Based on data generated about the user, the app’s home page is a highly specified locale for content that is meant ‘for you.’ TikTok is modeled after Douyin and refers to its home page as the ‘For You’ page.

The parent company of Douyin, ByteDance, saw the possibility of combining the effectiveness of their application with the ‘western’ reach of Musical.ly. In November of 2018, ByteDance reportedly paid $800 million dollars to purchase Musical.ly (Kunthara, 2020). They rebranded the application as TikTok in marketing efforts to North America and Europe. In the years following, it has seen tremendous success.

Similar to nearly all social media applications, TikTok’s business model is built on advertising revenue generated primarily by in-feed video advertisements, which appear alongside other user-generated posts, and ‘top-view advertisements,’ which users are forced to watch in their entirety to continue using the application’s services. To a lesser extent, the corporation receives revenue from optional, direct in-app user purchases, such as filters (Juneja, 2023). As of the publication of this article, TikTok’s assumed net worth is $75 billion. Their parent company ByteDance is assumed to be worth $425 billion (Wise, 2023).

The ethics of social media business models have come under scrutiny, exemplified by a statement made in the 2020 Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma. “If you’re not paying for the product, then you are the product” (Orlowski, 2020).

There have been numerous ethical and political privacy concerns surrounding TikTok. According to the app’s privacy policy, TikTok’s parent company ByteDance collects data about which videos are watched and commented on, your location, phone model and operating system, and keystroke rhythms (Tidy, J., & Smith, S., 2020). All of this information goes into making the app, especially its home page, more responsive to the user’s interests. This amount of data collection has caused a number of privacy concerns, prompting nations, including India, to ban the app. In the United States, former President Trump threatened a ban in 2020. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo claimed it was among numerous applications “feeding data directly to the Chinese Communist Party” (BBC, 2020).

In March of 2023, TikTok C.E.O. Shou Chew was called in for more than five hours of questioning by a United States Congressional Committee to investigate the corporation’s impacts on young users, data privacy concerns, and most contested, the company’s ties to China (Kang et al., 2023).

It is important to note, however, that TikTok is collecting an equivalent amount of data to the American social media app, Facebook. It is simply the nationality of the company the data is reported to that varies (Tidy, J., & Smith, S., 2020).

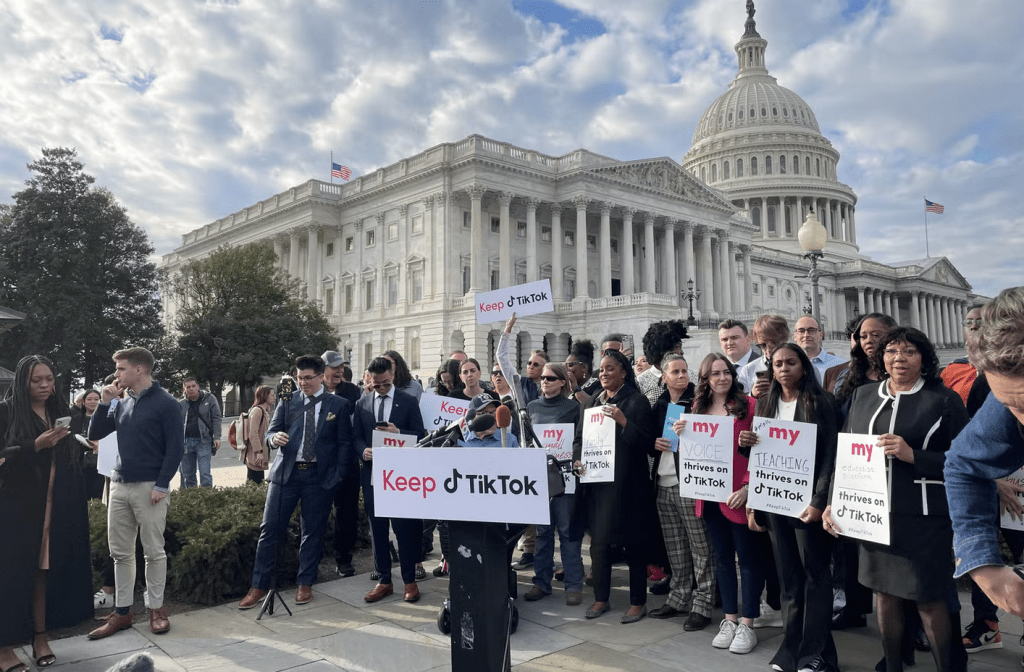

The possibility of a nation-wide ban on the application has created a discourse regarding privacy concerns versus connection and public advocacy. Many users protested the hearings outside of Capitol Hill (Docter, 2023).

Protestors outside the March Congressional Hearing. Photo by Hannah Docter-Loeb, Slate

Despite this ethical and political economic discourse, users cannot get enough of TikTok. In 2022, five years after its launch, TikTok had 1 billion active monthly users who spent an average of 850 minutes per month viewing the app’s content (Geyser, 2022).

The kinds of videos viewers are watching varies. TikToks can be posted by any user, but the application’s algorithm promotes content produced by ‘influencers.’ These creators are paid by TikTok and other corporations to promote products to their large follower base.

By the end of 2022 the influencer industry was expected to see a market of $16.4 billion, (Santora, 2022, Table 1) which is the equivalent to the gross domestic product of a small nation, like Georgia or Laos (World Population Review, 2022, Table 1). While these figures reference the influencer market on a global scale, the vast majority of the revenue is integrated into the U.S. economy. As the name of these marketers suggests, this economic sphere exercises a massive influence over U.S. culture.

Influencers are eligible to enter TikTok’s “Creator Fund” once they’ve amassed 10,000 followers, and have reached at least 100,000 video views in the last 30 days (TikTok, 2022). This money comes from ByteDance, which caused scrutiny, since members of the Chinese Communist Party have a direct stake in the company (Hutchinson, 2022).

Social media influencers’ incomes are not limited to direct payment from apps. Corporations recruit social media personas with large followings to promote products and/or services for pay. This can be done quite discreetly, like when a content creator ‘just so happens’ to be wearing, say, a designer brand. When they talk in their short video, they state what brand the item is, and conveniently link viewers to a purchasing point. This can also be done more explicitly, like when they make a video that is clearly an advertisement.

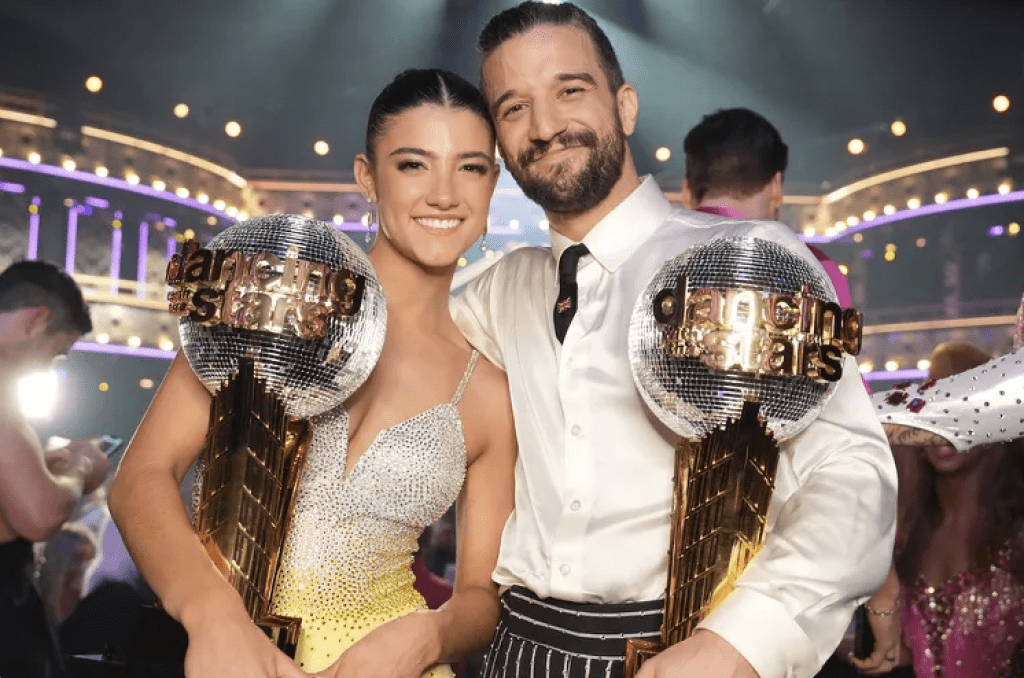

Let us look at a case example with the influencer Charli D’Amelio. The eighteen-year-old gained popularity on TikTok initially for her dancing videos, which is logical, being that the platform had prior been Musical.ly, which only consisted of this kind of content. As of April 2023, D’Amelio has 150.5 million TikTok followers, and her content has been liked 11.3 billion times. She has a clothing brand, a makeup brand, and was the 2022 winner of the TV talent competition, Dancing With the Stars.

D’Amelio, the influencer for 150 million, poses with co-star Mark Ballas on Dancing With the Stars. Photo by Eric McCandless for ABC, Featured in People Magazine.

Naturally, D’Amelio is involved in a number of marketing campaigns in ways that are often unknown by the viewer. An example of indirect sponsorship occurred in a September 10, 2022 TikTok post in which D’Amelio can be seen riding in a car drinking a Dunkin’ Donuts coffee. To an unaware eye, the video is a teenager getting morning fuel on the way to a commitment, but in fact the coffee brand sponsors D’Amelio, and even sold a coffee called the “Charli,” in order to market their business to her younger fans. It presumably worked; when one searches “Dunkin’ Donuts” on the application, one is met with a seemingly never ending supply of young viewers consuming the company’s coffees and pastries.

In this one example of influence alone, D’Amelio, and subsequently her media, were utilized to cause a cultural shift, serving the economic “base” represented by Dunkin’ Donuts. Habits of coffee consumption changed, thus changing the cultural practices of young people.

TikTok is utilized to not only affect what viewers consume, but how they present their identity to the world. Fashion is one of the most prevalent examples of this notion. The way one dresses reveals their identity and persona (Barnard, 2014). TikTok has completely changed today’s fashion market and its trends. In a 2020 article, Vogue reported that TikTok creators are leading global clothing trends (Allaire, 2020).

TikToker modeling the boots in question.

A recent example of this can be seen with boots. Frye is a fashion brand that has specialized in leather boots since 1863. The company completely rebranded in 2016, (Frye, 2020), but had not garnered much interest from the general public until this past year on TikTok. The “Campus 14L” knee high, tan leather boots are sold for $498 (Frye Company). Recently, these shoes have become a ‘staple’ for many fashion influencers on TikTok, with the search “Frye Boots” producing countless results of creators, overwhelmingly women, styling the shoes. In an August 30, 2022 post with nearly 30,000 views, a TikToker explains how she went to the Real Real, a vintage designer resale website, to purchase the boots at a lower cost than retail. (Tucker, 2022). “These Frye boots might be my favorite item in my closet,” one user said (Cristine, 2022).

This fashion trend is an interesting example of the economic dynamics of TikTok, as Frye did not explicitly pay to have their boots become popular. However, because more and more influencers shared their love for the shoes, the market increased, selling out Frye’s stock. Other corporations have gotten on this trend; in fall of 2022, Target created a knockoff of the boots that retails at $40. The market called for a new ‘it’ boot, and Frye became the answer. Capitalist consumerism on TikTok changed the ‘superstructure’ of what stylish boots look like, and corporations like Frye, the Real Real, and Target all benefited.

Fashion is just one example of how corporate interest impacts culture on TikTok. The application has also been known to alter what people believe; political ideation and polarization have been connected to the platform.

The New York Times reported in the autumn of 2020 on TikTok’s influence in the political sphere, primarily with young viewers. The problem lies in TikTok’s “For You” page. While it can be as innocent as knowing which shoes a certain viewer will like, it can also function as a gateway to polarization. In the NYT story, Ioana Literat, an assistant professor of communication and media at Teachers College, Columbia University, said, “in terms of youth political expression, while there’s a dynamic and influential liberal activist community on TikTok, there’s actually plenty of conservative political expression, and pro-Trump voices definitely find an audience on the platform,” (Herrman, 2022).

Graphic from The Guardian

This notion can be seen with the TikToker “pennycandy8787.” She has amassed more than 87,000 followers, and her content has been liked more than 500,000 times. One of her most popular posts from May 2021 is an intended comedy video viewed by 171,000 people. She is wearing a Trump hat, with the American flag behind her. The screen reads, “Get Vaccinated or go to jail.” A song begins to play, featuring country artist Morgan Wallen singing: “I can see me sitting in the back of a cop car” (Pennycandy8787, 2021).

What is nuanced and interesting in this example is the fact that this TikToker is a self-proclaimed Washington DC resident who works in politics. While she comes off as a ‘relatable conservative’ in her videos, she is likely propelling interests that work to serve her and her employment. Her political content, an example of cultural ‘superstructure,’ has its footing in a foundational ‘base’ of self-serving economic interests. Political ideation and polarization on TikTok are a way in which the Marxist, capitalistic ‘base’ affects the ‘superstructure,’ in this case, culture as it relates to politics.

From TikTok’s perpetuation of Dunkin’ Donuts’ corporate interest, Frye Boots’ connection to capitalist consumerism, and the far-right’s political polarization in young adults’ videos, Marx’s political economy theory is evident. In each one of these examples, the economic ‘base’ affects the cultural ‘superstructure.’ In each case, culture’s fascinations are consequently tied to corporate interests. An examination into TikTok provides a new lens into Marx’s political, economic, and capitalistic theory. The rapid expansion and reach of social media provides a new scale, specification, and fascination, in understanding materialist culture.

As one creator poignantly, unassumedly says, while holding her new $400 Frye boots, “it’s safe to say I was influenced” (Lubinic, 2022).

About the Author:

Megan Robertson (she/her) is a third-year Media Studies and Performing Arts & Social Justice double major. Originally from Dalton, Georgia, she is a writer, artist, and activist interested in the intersection of media, art, and community advocacy. She is a staff writer for Grain of Salt Magazine, the host of Drive your Funky Soul on KUSF.org, and starting in Fall 2023 will be the Editor in Chief of the San Francisco Foghorn. She is currently on a semester abroad in Paris, France. See more of her work at megrrobertson.com.

Megan Robertson (she/her) is a third-year Media Studies and Performing Arts & Social Justice double major. Originally from Dalton, Georgia, she is a writer, artist, and activist interested in the intersection of media, art, and community advocacy. She is a staff writer for Grain of Salt Magazine, the host of Drive your Funky Soul on KUSF.org, and starting in Fall 2023 will be the Editor in Chief of the San Francisco Foghorn. She is currently on a semester abroad in Paris, France. See more of her work at megrrobertson.com.

References:

Allaire, C. (2020, December 28). How TikTok Changed Fashion This Year. Vogue.

BBC. (2020, August 3). TikTok: Pompeo says Trump to crack down on Chinese software in coming days. BBC.

Barnard, M. (2014). Fashion Theory: An Introduction. Taylor & Francis Group.

Berger, A. A. (2018). Media Analysis Techniques. SAGE Publications.

Carson, B. (2016, May 28). The Inside Story of Musical.ly. Business Insider.

Chan, S. (2021, December). Global Consumer Spending in Mobile Apps Reached $133 Billion in 2021, Up Nearly 20% from 2020. Sensor Tower.

Christine, J. (2022, September 5). TikTok. TikTok.

The Citizen Lab. (2021, March 22). TikTok and Douyin Explained. The Citizen Lab.

D’Amelio, C. (2022, September 10). TikTok. TikTok.

Docter, H. (2023, March 23). TikTok Hearing: Influencers make their case to the press.

Durham, M. G., & Kellner, D. M. (Eds.). (2012). Media and Cultural Studies: Keyworks. Wiley.

Frye Company. (2018, December 5). Women’s Boots.

Fuller, A. (2015). The Art of Truth: Maxim Kantor. University of Notre Dame.

Geyser, W. (2022, July 14). The Incredible Rise of TikTok – [TikTok Growth Visualization]. Influencer Marketing Hub.

Geyser, W. (2022, August 1). TikTok Statistics – 63 TikTok Stats You Need to Know [2022 Update]. Influencer Marketing Hub.

Herrman, J. (2020, June 28). TikTok Is Shaping Politics. But How? The New York Times.

Hutchinson, A. (2022, July 18). TikTok’s Defending Itself on Several Fronts as Pressure Rises on the Chinese-Owned App. Social Media Today.

Juneja, P. (2023). The TikTok Business Model. Management Study Guide.

Kang, C., McCabe, D., & Maheshwari, S. (2023, March 25). Lawmakers Appear Unconvinced by TikTok Chief’s Testimony. The New York Times.

Kemp, S. (2022, July 21). The Global State of Digital in July 2022 — DataReportal – Global Digital Insights. DataReportal.

Kunthara, S. (2020, August 28). As Companies Battle For TikTok, A Look Back At Its Funding History. Crunchbase News.

Lubinic, R. (2022, September 23). TikTok. TikTok.

McLellan, D. T. (2022, August 23). Karl Marx | Books, Theory, Beliefs, Children, Communism, Sociology, Religion, & Facts. Britannica.

Orlowski, J. (Director). (2020). The Social Dilemma [Film]. Netflix.

pennycandy8787. (2021, May). TikTok. TikTok. Retrieved September 25, 2022, from

Ruby, D. (2023, March 20). Social Media Users In The World — (2023 Demographics). Demand Sage.

Santora, J. (2022, August 3). Key Influencer Marketing Statistics You Need to Know for 2022. Influencer Marketing Hub.

Tidy, J., & Smith, S. (2020, August 5). TikTok: The story of a social media giant. BBC.

TikTok Creator Fund: Your questions answered | TikTok Newsroom. (2022). Newsroom | TikTok.

Tucker, C. (2022, August 30). TikTok. TikTok.

Wise, J. (2023, February 28). How Much is TikTok Worth in 2023? Here’s the Latest Data. EarthWeb.

World Population Review. (2022). GDP Ranked by Country 2022. World Population Review.