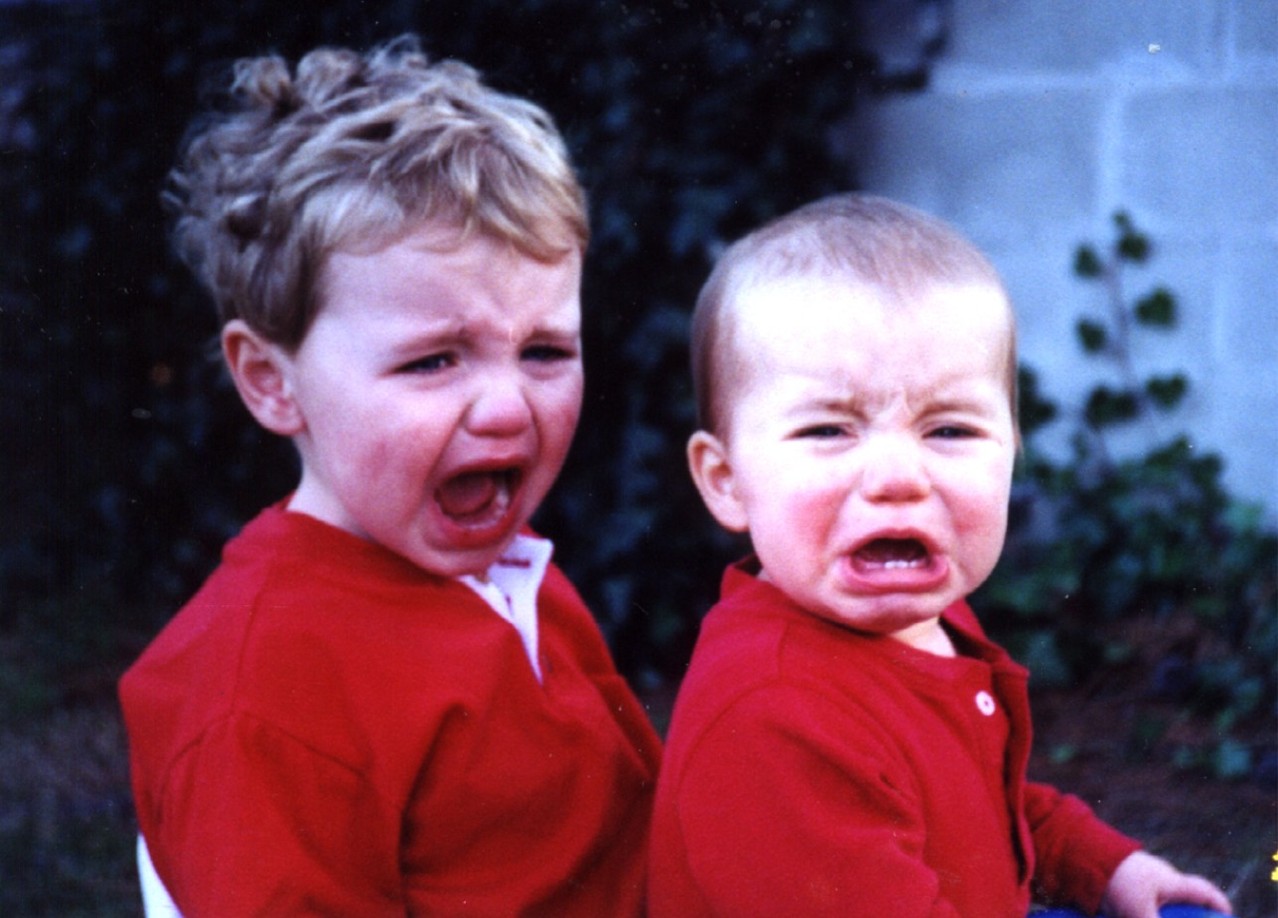

Before the age of three, children develop rapidly in every area of their lives. However, the social and emotional skills needed for impulse control, understanding others’ points of views and communicating their experiences have not fully matured. This may help explain why young children sometimes express their emotions so intensely, disproportionately, or spontaneously [1].

Frustration and temper ‘tantrums’ are often classic responses that children have to situations that are not going their way. Even with the most attuned and responsive parent, toddlers are bound to encounter overwhelming emotions such as disappointment, rage, joy, and fear that may be challenging to make sense of and express appropriately.

How can parents use these emotional experiences to teach children how to handle powerful emotions?

- Set an example by staying calm. Negative feelings can be very difficult to tolerate, and the child’s reaction (for example, throwing themselves on the floor in protest at the grocery store) can trigger automatic responses of rage, impatience or even despair in the caregiver. These are valid and common feelings that often create barriers to parents responding effectively and supportively. In such moments, the first thing caregivers can do to stay calm is to take a few deep breaths. This strategy may seem too simple to work in stressful situations, but breathing is shown to have physiological benefits that translate into more positive interactions with your child. For starters, deep breathing decreases the level of adrenaline in the blood stream, which typically produces feelings of anxiety. Lowering adrenaline will help slow down the heart rate, and allow for the release of a hormone called oxytocin, which is known for making us more calm and empathic in the presence of loved ones.[2]

- Wait until the tantrum is over to teach manners. Yes, it is important to teach children to delay gratification or to adjust to social norms, and an important task of parenting is to set boundaries and be consistent. But when kids are emotionally overwhelmed (too scared, mad, or sad), they will not be capable of listening to reason or rules. If caregivers breathe, count to 10 slowly, or do whatever works for them to respond to the child’s emotion (for example hug the child until she calms down), they’ll have a better chance of teaching valuable lessons after the emotional peak has subsided.

- Once the outburst or tantrum is over, talk about it together. Even when toddlers have not developed their vocabulary fully, they can understand much of what adults say. Caregivers who discuss what happened and name the emotions felt by all involved (e.g. parents, child, siblings/peers) are supporting their child to identify and ultimately regulate their emotional responses. Parents can say things like: “When mommy said ‘no,’ that made you so mad“, and “When you hit me, it hurt and made me very sad.”

- Parents can also provide alternatives to the child’s behavior during these moments by saying something like, “maybe next time you feel that way, you can say, ‘mommy I am so mad at you!’ and we can try to find a way to make you feel better so you don’t have to hit mommy to let her know how bad you feel.” For slightly older children, caregivers may try including them in the process to find a more productive response by saying, “next time, what else do you think you could try?”

For parents to be able to grow from these experiences, it is important for them to engage in self-reflection just as they encourage their children to do the same. You might ask yourself questions such as “How do I feel when my child is feeling angry, sad, or scared? How much am I able to tolerate feelings of frustration? Is it OK with me when my child expresses anger toward me or others?” Such questions help to identify your triggers and responses so that you too, are appropriately responding to your child in the moment and can help you be more effective when something similar happens again.

[1] Lieberman, A. F. (1993). The emotional life of the toddler. New York, NY: Free Press

[2] Windle, R. J., Shanks, N., Lightman, S. L., & Ingram, C. D. (1997). Central oxytocin administration reduces stress-induced corticosterone release and anxiety behavior in rats 1. Endocrinology, 138(7), 2829-2834. doi:10.1210/endo.138.7.5255