Genevieve Negrón-Gonzales, Assistant Professor in the School of Education, shares details about creating a five-year plan.

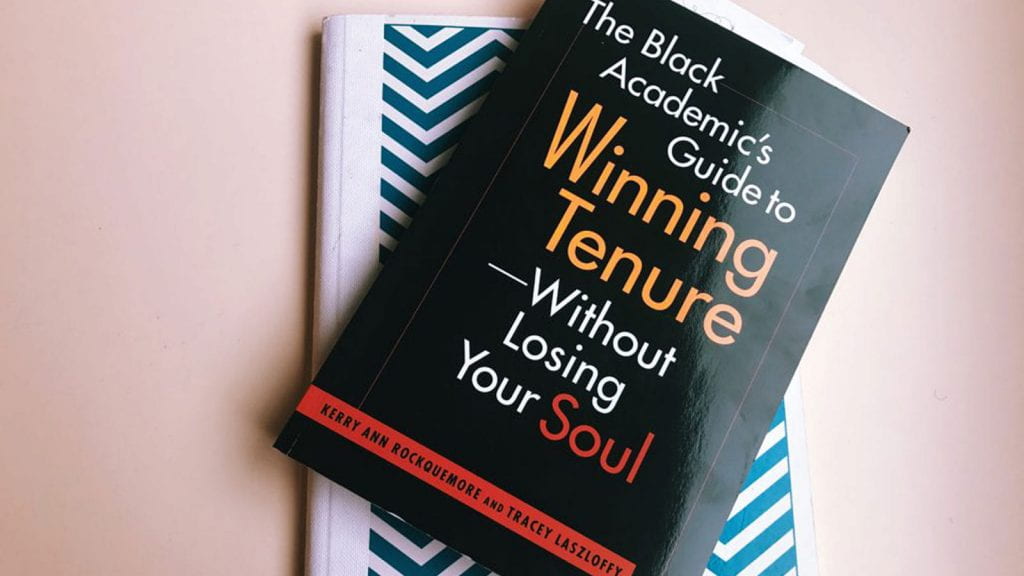

Earlier this semester, School of Management Associate Professor Michelle Millar and I facilitated a workshop sponsored by CRASE titled “Making a Five-Year Plan: A Workshop for Faculty.” Attended largely by early-career faculty from across campus, the session was intended to demystify the tenure process by breaking the benchmarks towards tenure and promotion down into a series of concrete, specific goals that can be mapped on to a five-year calendar. Our approach is influenced by the work of Kerry Ann Rockquemore and Tracey Laszloffy in their book The Black Academic’s Guide to Winning Tenure – Without Losing Your Soul. The book, written for Black faculty specifically and faculty members from underrepresented communities in general, lays out a helpful approach towards the pre-tenure years of faculty life, including the critical importance of developing a five-year plan, for anyone going through the tenure and promotion (T&P) process.

We began by clarifying that, though often talked about as a seven-year process, promotion from assistant to associate professor is actually five years. The seventh year is the sabbatical year, and the sixth year is when one submits the T&P file, which means that work for the T&P file must to be accomplished by the end of the fifth year. Though every faculty member’s tenure file will be judged by a university-wide committee, the expectations of what makes a strong tenure case vary by discipline, field, and school, and therefore the first step before developing one’s five-year plan is to clarify what those expectations are with mentors and senior faculty.

There are several reasons a five-year plan is important, including the tension between tenure being a benchmark that must be achieved on a fixed timeframe and the fact that it is measured with a nebulous set of benchmarks; the reality of the nature of academia and that it is entirely possible to work a 16-hour day attending only to the immediate tasks at hand and never getting to the bigger projects like writing and thinking; and, how the “never enough” culture in academia is not only a recipe for burnout but can also negatively impact productivity. A five-year plan can help mitigate those challenges and even build in time for rest and recuperation.

Below are the four steps we see as the keys to developing a solid five-year plan:

Step One: Articulate SMART goals in each of the following areas: research, teaching, and service.

The first step is to develop goals that are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, & Timely (SMART). So, rather than just writing furiously, you are clear about the specific goals you need to meet over the course of the five years. For example, a goal related to research might be to publish an empirical piece in a top journal in your field based on data you have already collected.

Step Two: Develop a list of tasks to accomplish each goal.

Next, break down each goal into a series of concrete tasks that will help you accomplish the goal—the more specific the better. The publication goal listed above could be broken down into the following tasks: analyze data; develop the article; argument and outline; write a draft of the article; revise article after getting feedback from a colleague; and submit the article.

Step Three: Use the technique of “backward calendering” to time-map each goal and it’s corresponding tasks.

Nothing helps you be realistic about what you can accomplish and how long it will take than pulling out a calendar and mapping it out. Start with the due date and work backwards, mapping out each task on a specific day. If you aim to submit your article on August 15, you’ll need to get feedback from your colleague by August 1, which means you’ll need to get it to her by July 1. To get it to her by July 1, you’ll need a full draft by June 15, develop your argument and outline by May 15, and have your data analyzed by April 15. If you anticipate the data analysis will take you two months, you’ll need to start data analysis by February 15.

Step Four: Map out each year and adjust as necessary.

Though it can feel overwhelming, it is important to backward-calendar each goal. This will help you think through what is really possible, how to stagger different projects, and how to build in the time necessary for each task. It also helps you look at each semester one-at-a-time, and shuffle things around as needed so that you can ensure that you are evenly distributing the work and taking into account how other responsibilities (a heavy fall teaching load) or opportunities (summer off) will increase or decrease your work in a given period.

Lastly, keep in mind that your plan is fluid. It can be adjusted as needed – tasks can be removed or added, and goals can change. That’s okay. However, a five-year plan is worthless if you develop it in a workshop and never look at it again! A five-year plan is lived through semester-long plans, which we recommend drafting at the start of each term. Developing a “Sunday Meeting” is also a helpful tool; whether this is with an accountability group you set up (see the Rockquemore and Laszloffy book for more details on this!) or by yourself. Setting aside time each Sunday to revisit your semester plan, and figure out what you need to do that week in order to stay on track, helps bring your five-year-plan into your everyday life.