Rick Ayers, Assistant Professor in Teacher Education at the University of San Francisco and Huffington Post blogger, walks through his process for writing a blog post with a bunch of tacked on advice, ideas, and encouragements.

A walk through my writing process and a bunch of tacked on advice, ideas, and encouragements.

Knowledge is socially constructed. So are blog posts. To write a piece of public advocacy is not accomplished by you sitting staring at the screen. It is the result of ongoing engagement – with colleagues, with the public, with your classes. Often a blog post is strung together from wide-ranging conversations you have had, including some insights you have gotten and others you picked up from others.

I remember the debates about the Vietnam War when I was a freshman at the University of Michigan. I knew I was against the war but was not adept at all the arguments. When some students raised a protest against military recruiting on campus, hundreds of people gathered in front of the army table. I would argue with someone until I got stuck on a point. Then I would wander around and listen to other debates, searching for someone who could answer the point that stumped me. Then I would return to the fray. It was a roiling mass of people, made up of dozens of smaller discussions. And it was a powerful education in debate and how to engage and persuade.

Unfortunately, academics often see ourselves as isolated, toiling away in offices and libraries. But engaged scholarship calls on us to be engaged in the debates in the world, to always be alert to issues that are impacting communities and to arguments that need to be heard. You will never craft the best argument while just in that cubicle. You have to be testing it out, as during the Vietnam debates, to hone your point and help make it understandable. Kevin Kumashiro often talks about our responsibility to be “framing” the debates, looking at the fundamental assumptions that drive a policy and how to challenge them. I reject the idea that knowledge is “created” at the university level. Knowledge is in practice, in the community. Our contribution is to understand struggles on the ground and how to represent and advance those struggles.

How to get started: Start with a moment. Not a constructed story for an article but actually something that happened that got you thinking. If you pay attention to your interactions, these will come up as the genesis of pieces. For me this might be a classroom interaction, a demonstration or event in the community, or even driving and listening to NPR. Even if you don’t start your blog post with this story, you write it down.

This also suggests that you should use the first person pronoun and point of view. Well, not always. But quite often you should. At least I think you should in order to find your voice and to move into a more relaxed, genuine way of writing. When I first started writing for Huffington Post, an editor gave me the advice to “write like you are sending an email to a friend.” That is a great idea. I try to do that but in fact my pieces end up being a bit more formal than an email – they really are small essays. But at least thinking of an email moves one off the “stuck” place of staring at the screen. And it pushes the style to a more mass audience, not an academic one.

To start: An interaction, discomfort. Describe the picture.

So below is an example of an incident I experience that troubled me, as I began to wonder if this is something I should pursue and write about:

Committee meeting, representatives from different constituencies.

“The problem is,” I ventured, “there is very little you can tell from a standardized test of students and then to tie evaluation of that teacher to performance of those students becomes even less valid and finally trying to compare professional development graduates to other teachers is just a fool’s errand.” That was my intervention in the discussion, a big dissention blurted out.

It was a meeting of a collaboration group for an innovative summer professional development teaching project – I was a visiting professor in a medium-sized California city, Charley was from the professional development non-profit and Greg was from the school district. We were discussing evaluation data to send to the granting agencies and Charles had suggested that we collect “Better Balance” test scores from our graduates and compare to other teachers. I was immediately doubtful – not only that this measure would distort and narrow the teaching practices of our graduates, but that it would provide support and validation for the advocates of value added evaluation across the state.

Greg, the district guy, showed no interest in my comment. He did not even raise himself to disagree or debate me. He simply declared, “The superintendent wants these numbers (on the test) and we are collecting them so they can be used as data.” The look in his eyes, the subtext of his dismissal, was essentially, “What is this pinhead talking about? It’s irrelevant.”

Charles actually agreed with me. He is a progressive educator who knows the debates and the game. Why, then, had he made this proposal? It was, of course, the pressure of the grant. Both foundation and federal grants for the professional development program required “quantitative” data to determine if our graduates were effective.

Now I realized that this article might put Charles, Greg, me in a difficult situation. While I had fictional names for the main characters, I decided to go back and fictionalize the place and the program. Still probably a weak disguise but the best I could do.

Extending the idea:

So there was an idea, a conflict. How did I regard it? What was behind it? And, even now, I had to think: if I were to write it up, what is the audience, who needs to hear about this, why would I write it up? I began to think about people working in these different spaces, the non-profits, the universities, the school districts, and the built-in tension between their missions. They could use a discussion and clarification – and this article could contribute to that. More broadly, what does this situation tell us about problems in education policy and the corporate “reform” agenda?

So this is the period of reflection, open-ended exploration of the issue. For some people that means writing a mind map, a web, or simply notes. It is also a time to talk to others about the problem, the issue.

In the course of writing this piece, I talked to a lot of colleagues about this issue – Sepehr, Lance, Monisha, Uma, Lillian. I wasn’t always asking for input, I was just trying to explain the point, see how it would take, how to best articulate it.

The first thing I was thinking about was the problem for non-profits, the problem people in these positions have because they have to fulfill requirements of the grant in order to get the next phase of the grant paid. I thought about other institutions I know who face tensions and challenges to their mission because of the demands of the grants. I have seen this is places like Youth Speaks and Youth Radio. They start with a radical, outside-the-box project and they are wildly popular with youth who flock to them, turning their backs on formal schooling. Then the non-profit finds itself trying to sustain a staff and a budget and go for grants. And the grants insist that they take these youth and turn them back towards the schools, that they show “progress” in matriculation, grades, etc. I have been in discussions with people in these non-profits and have also discussed the problem from the other side, as my brother was on the board of the Woods Fund in Chicago and they struggled with how to make their grant structures more honest. I reflected on how difficult it is to be in a grant-driven non-profit. That was the context within which I recognized the different positionality of Charles, for instance, from me. So I wrote:

The challenge for Charles was that he was ruled by the terms of the grant. And for the grant he had to bring data – proof of success. Some data could be qualitative (reports from teachers, supervisors, principals, students) but some had to be quantitative. People who live by grants find themselves spending a lot of time worrying about the reporting, the data. And often the terms of grants practically compel the recipients to be fraudulent, to make things up. Because most grants require that you define problem and then declare that when you get so many thousands of dollars you will provide a solution of the problem. But too often the problems are deep, structural, and difficult to move the needle on. Open-ended grants might allow projects that are exploratory or generative for participants. But generally grants are for some kind of linear “improvement.”

While in education research studies, “value added” teacher evaluation (basically evaluating teacher effectiveness by tracking improvements in the test scores of their students) has been demonstrated to be invalid, Charles felt compelled to put that idea in the assessment package.

Rereading and editing:

I went back and read the draft a few times. I noticed that I said “discussed” and “problem” a few times in the same sentence so I did some clean-up, drawing in new words.

Sometimes I just had to rewrite for clarity. I had written:

Open-ended grants might allow projects that are exploratory or generative for participants. But generally grants are for some kind of linear “improvement.”

But the problem was that this sentence butted in too abruptly after the last one. Is a grant being “open-ended” in contrast to the grants I’m discussing in the paragraph? Yes it is but I have to make that more clear. Thus:

If you manage to get an open-ended grant, this might allow projects that are exploratory or generative for participants. But generally grants in education demand some kind of linear “improvement.”

There are a lot of thoughts packed in these 2 sentences but I also don’t want the blog to get over-long. Are these sentences simple enough to allow me to go on? But do they carry the thought I’m trying to communicate?

Halfway through it was important to stop and ask a question to myself. What is this piece about? It’s not just about my discomfort at raising the objection to value added assessment. It’s about how our different approaches to data-gathering arose not from the facts but from our different positions, who we reported to. I’m taking the long way around to try to defend the university as an organization crucial to open inquiry and real progress. So I had to explain more about grant-driven, foundation-funded educational projects.

And I had found myself in this meeting wondering about my privilege, the flip side of the discomfort felt by scholars of color when they intervene in such a situation. For them, the subjective pressure, communicated through raised eyebrows and lowered gazes, tells them that they are not academically worthy, they are being emotional. For me, in the white privileged side, the internal question reads more like: who am I to raise this methodological objection? Who is this privileged academic to make the pathway for our student teachers, and the access to grant money, difficult for his abstract concerns?

Indeed, in my high school teaching and in teacher education, I am always mindful of my responsibility to support marginalized students through the gatekeepers even as I argue and debate that the gatekeepers are invalid. To not do the former would be to sacrifice students in front of me who are doing well to my radical vision; to not do the latter is to sacrifice the futures of the vast majority of my students in the project of courting success for the lucky few. So I was also seeking a tone that was not arrogant, not preachy; rather it was to simply point out the material structures that underlay the discussion.

At this point I started reflecting on a talk I heard some years ago by Arundhati Roy about the negative impact of NGO’s on radical social movements. Also I was thinking back on a section we had on the Freedom Schools in Mississippi in 1964 that demonstrated what independent activism looked like. I was not sure if I was wandering too far afield from my main point; but it seemed to be the best way to jump to a broader analysis of the problem. I signaled the transition to this reflection with a one-sentence paragraph.

How does the world of non-profits, the social justice enterprise funded by grants, affect our work?

Some years ago, Indian novelist and activist Arundhati Roy made a scathing critique of the role of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) in containing social movements even as they “professionalize” activism. Her point was that many activists who in the past would have gone into radical, non-sanctioned, community-based liberation organizations were now being brought into NGOs – where they could make a decent salary and where their every move was framed by grant reporting – long proposals, narrow goals, and constrained possibilities. It was the kind of “repressive tolerance” of sponsored dissent that Marcuse had warned against.

Writing an outline halfway through:

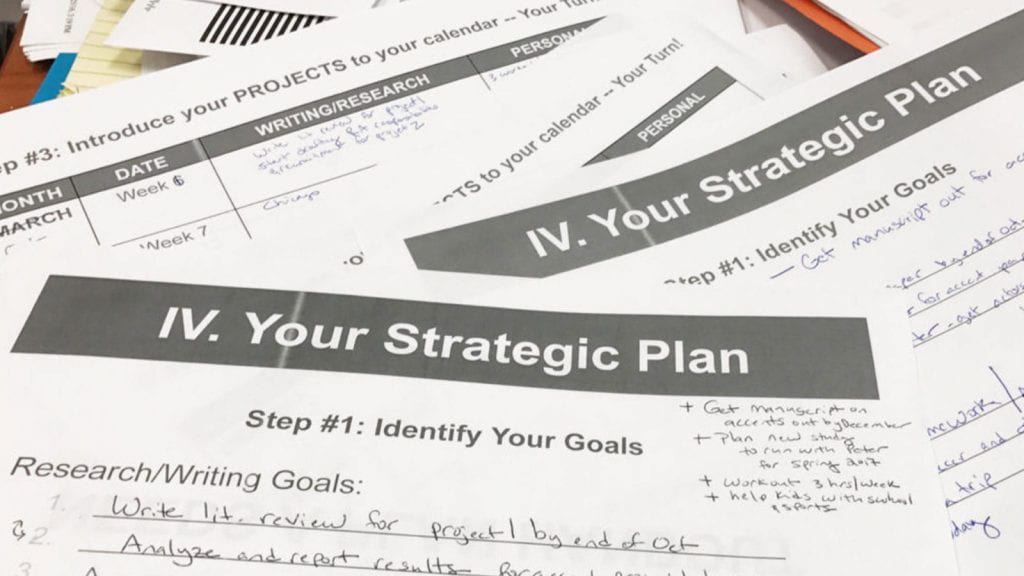

And there was still a jumble of things I wanted to say. So I made a rough bullet-point outline as to where I thought this was going, so I could just elaborate and explain each of the points:

- Arundhati Roy – C Cobb

- Foundations so big. Federal government now competitive grants.

- Two points: 1) they are big because of tax issue; 2) they are authoritarian.

- Universities. Regarded as out of touch. Foundations as source of money → Opposite of tenure or union protection

I also came across this article that demonstrates federal support for privatization, which, much like federal dollars for segregated housing after World War II, has long term impacts.

Generally in this writing I make no footnotes and no references to another author. For example I wrote a piece a few weeks ago about the police. I asserted that the police are the only people in society who are allowed by the state to use “legitimate violence.” This phrase is something that Walter Benjamin coined in the 30’s in discussion of the state and repression. I could have put a footnote. Or I could have said, “what Walter Benjamin called ‘legitimate violence.’” But really, why? If anyone asked me more about this, I could point them to Benjamin. Otherwise I could just claim and use the phrase because, well because it is a great way to put it. That is a way of owning an idea and asserting one’s authority with the idea. Academics often find themselves footnoting and referencing others throughout their prose. Try writing with no references – just to feel how liberating it is.

And after making an outline of how I would end it, I sometimes would just throw down random sentences, notes to self, as to how I planned to argue the point. For example:

Under grant you are cowering

When I raise a criticism of testing or value added, I feel like an egghead, out of touch with reality. Reality is the grant.

Problem of foundations have money because capitalists keep all profits

Taxes should have taken some of these resources – created by social labor – for democratic determination of where to go.

Foundations run things.

So I wrote:

Nonprofit organizations inside the US occupy the same space. People who want to improve conditions for oppressed students, who want to challenge inequities, are not leading demonstrations in Jackson, Mississippi, or in Oakland, California. Instead they are working for improvement within foundation and government-funded nonprofits. The revolution may not be televised but apparently it will be funded.

It makes me think back to the Mississippi Freedom Schools that started as an adjunct to the voter education organizing there in 1964. Charlie Cobb wrote up a proposal for the freedom school project. Where today under a foundation grant it would be a 25-page (or a 200 page!) document with extensive claims about the situation they were facing and the exact outcomes they planned to achieve, Cobb’s proposal was two pages long and defined exactly the purpose of the schools. It is a document that launched one of the most dynamic educational initiatives in the US and today is still studied as a classic artifact of movement history.

Certainly funding is a good thing. Initiatives for change should be funded and organizing campaigns need resources. But the question of who is doing the funding and what their underlying goals are – this is the rub. Too often, the fundamental world view and values of the funders are written into the kinds of problems they will entertain and kinds of measurements they demand to determine success. In this way, funding takes a social change project off track.

And foundations, private funding, have become such a huge part of the educational landscape that we accept without question that so many projects should be sustained by these kinds of grants. Indeed the federal government, whose responsibility is to raise money through taxes and disperse it to communities for their education projects, now mimics the private sector – only giving out most funds through competitive grants. Indeed, the largest of the grants we were discussing about the professional development program was a federal competitive grant.

One problem we have is that we tend to get caught up on our present reality, normalize it as if that’s the way it has to be. Living in the grant-driven world, channeling our social justice activism through non-profits, makes us begin to think this is just the way things are. In this way, the hegemonic mind-set of neo-liberal market-driven systems colonizes our minds. And how did it come to be this way?

Trying to wrap it up:

This discussion about foundations making education policy takes me back to a point Mike Klonsky in Chicago made to me many years ago. It is something that has stuck with me. And I have said it often while speaking or teaching. It is this: The reason foundations are over rich and able to set policy is simply that they are not being taxed enough. Those resources the1% hoard are produced by social labor and in general tax policies are there to collect some of those resources to use for broader social purposes – building roads, supporting schools and health care, etc. This method suggests that there will be at least a somewhat democratic process in decisions about the disposition of those resources.

So I wrote:

One of the main culprits in this shameful development is the changing tax structure. Starting after World War II but accelerating ridiculously in Reagan era, the taxing of the wealthy has changed enormously. Where excess wealth created by society was once gathered through taxes and then distributed through at least somewhat democratic decision-making processes, now it goes almost exclusively into the pockets of the one per cent. How does the Broad Foundation, the Gates Foundation, the Walton Foundation have all these billions of dollars? It is because they have not been taxed enough. Resources that should be distributed through public projects are now in the pockets of individuals.

It follows then that the structure of grants and their reporting responsibility is a much more authoritarian way to make decisions than the democratic process of a community deciding how to prioritize education projects through a locally elected board. The grant does not ask your opinion. The grant says: do this, do that. It establishes instrumental goals, goals directed towards narrow, concrete outcomes that can be quantified. And we see evidence every day that the federal government is completely bought into the privatization project, restructuring education like top-down corporations.

Looking back on the piece so far, I reflected that it is an important issues and one I could try to reframe the discussion on. But the title was boring. I had called it, “Foundations and the Dumbing Down of Activism,” and, while that said something of what I wanted, the very first word “foundations” was going to put people to sleep. I’m thinking now of calling it “The Revolution Will Not Be Funded.” That does not explain much of what will be in the piece but it will grab attention.

Now the piece was driving towards the end. I had jotted down some other notes at the bottom of the page about the university and open inquiry:

But actually academic world is what it should be – freer. Under grants they must bow down. Actually you want the deeper read. Grantees don’t go deep. Backward planning.

Why universities with inquiry built the greatest educational system in the world.

When I raise a criticism of testing or value added, I feel like an egghead, out of touch with reality. Reality is the grant. But actually academic world is what it should be – freer. Under grants they must bow down. Actually you want the deeper read. Grantees don’t go deep. Backward planning. Why universities with inquiry built the greatest educational system in the world.

This would not be at all how I would write the ending but it contains, in raw form, thoughts I wanted to communicate. I hesitated to claim that US universities were the “greatest education system in the world” but I wanted to defend university freedoms. I need to think about that a little more. Also, there is a contradiction between the position that Arundhati Roy was extoling for activists – outsider, volunteer, community based guerrillas – and the position of university professor as somehow a better place to be than a non-profit. Many community organizers I knew in the 60’s left universities precisely because they were too constrained. But I don’t think I can go into all that. I’ll probably just leave this contradiction unaddressed.

So I wrote:

So the awkward moment when I raised objection to value added measurement truly reflected the different positionality of the three people in the room. When I raised the criticism of testing measures, I seemed like an abstract-thinking egghead, out of touch with reality. But such framing accepts the grant and its demands as reality, something not to be questioned. And it reminded me why universities are important.

Yes, universities that grant tenure, that allow freedom of inquiry, that protect professors to say aloud what they see. Universities now are under attack. According to the critics from the business world, universities have not enough clear outcomes, not enough measures of success. But the very open nature of university-based research and inquiry is what made the US educational system the most powerful engine for knowledge and understanding, the envy of the rest of the world. The narrowing of the university, the constraining of the inquiries of faculty through grant-driven projects, disallows us from pursuing the truth. Someone has to be in the room to declare the emperor’s new clothes to be a fraud. I felt fortunate to have the protection of my position in the university. But more and more, that is a voice that is silenced by the power of the foundations and now the federal government, who control the budgets.

Writing style:

I have made a number of comments along the way about writing style: write it like an email, think of a mass audience, use first person, leave out references. I would only add that you can find much of this kind of writing all over the place. Check out social media. Read Truthout, Jezebel, and Salon. Follow polemics, about issues large and small. Read New York Times for ideas. Always read Valerie Strauss column in the Washington Post.

I’m not even sure that I like this so much. It is fascinating to me but would anyone want to read it? Am I reaching for too many points? At this point, I would show the draft around to some of my friends and co-conspirator writers. Get feedback and edits. Then submit.