Monisha Bajaj in Conversation with Talia Knowles, CRASE Program Assistant

Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us! Please tell us about yourself. Where are you from? What do you like to do outside of academia?

Well, I’m a professor here at USF in international and multicultural education. I’m a parent. I have a ten year old child. So what are some of the things I like to do? We go to a lot of his games since he’s really into sports, so that tends to occupy a lot of our free time.

I have a lot of family in the Bay Area since I grew up here. After college, I moved abroad and to the East Coast. So in the 15 years that I was away from the Bay Area, I lived in Washington, D.C., in New York, as well as in three other countries for anywhere from 8 to 12 months.

The time I’m not at work is often spent with family, extended family, friends from childhood and friends from other parts of life who live here as well. I also like being in nature. I feel like I could always be in nature more.

What’s your favorite thing about the Bay Area?

I would say it’s just the open-mindedness that’s here because I’ve lived in a lot of different places. I feel like people in the Bay Area are really open to the world and there’s a global mindedness and an openness here. Even just at USF, there’s a sort of like baseline progressiveness and willingness to engage with themes of social justice. That isn’t always true in other places that I’ve lived.

How long have you worked at USF?

I started at USF in January of 2014 and one of the first communities I was roped into was the CRASE Advisory Board!

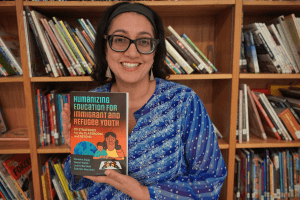

Can you tell us about your recent book?

This book, Humanizing Education for Immigrant and Refugee Youth: 20 Strategies for the Classroom and Beyond, started with an idea maybe about six years ago now.

I was doing research with two doctoral students at a high school for immigrant and refugee newcomer students in Oakland. We would go every week to work with the students and ran a club for them on human rights.

We’d do interviews with teachers, focus groups with students, activities with the students, and we also delved into the literature about immigrant and refugee youth. We wrote a few articles based on it, and as the project was ending and the data collection phase and writing was coming to an end, I kept thinking that it would make a good book, but I didn’t want to do another book for an academic audience. Yes, it would be interesting to profile what’s happening with these students in an academic way. But the need seemed to be, how do you get the lessons of what these students need into the hands of teachers who are serving these students? Most of them have never taken a class on how to work with immigrant and refugee students since it’s not required in teacher education.

So there’s a huge gap between teachers’ knowledge and what refugee, immigrant, and undocumented students really need. There are many needs that a lot of students and their families have. And some schools are really innovating and doing some really creative things. I would say that the school where we were doing research is on the cutting edge of some really creative things along with other schools we’ve heard about in other parts of the country.

That’s when the idea emerged to do a book project, not for people in academia necessarily, but more oriented towards educators, taking the research and making it very digestible, with no jargon. The strategy chapters are short and the book has a lot of other resources that teachers can reference, and then we included vignettes and narratives about immigrant and refugee students throughout the book to humanize the population of students that we’re talking about.

We heard some horror stories of places where kids were dropping out of school because no teacher even could speak Spanish at all. An entire school where 600 unaccompanied minors came in from Central America and not a single teacher could speak Spanish? There was an incident in Missouri a few years ago of an Afghan boy whose family was settled in a town with no Afghans or Muslims for miles and miles — no community support. He was really isolated and bullied and ended up committing suicide. This made us think about what it means when teachers and schools can’t integrate these students and address their needs.

Have you had any direct conversations with teachers who have read your book and been able to start implementing these strategies?

Because of COVID and the detours this book project took over the six years from when I had the idea and when it came out, we ended up adding a lot of contributing authors to the project. It was a lot of work to get all those voices and perspectives streamlined in the book and to make it cohesive. But what was beautiful about it is that we have 22 people who are affiliated with the book, and so different schools have used it for professional development. We’ve been invited to different conferences to present; we’ve shared it at bookstores, schools, and academic conferences. We have interacted with a lot of teachers who said that it’s been really useful in terms of the strategies.

We recently presented at a conference in New York that was for educators of newcomers from around the country, and a bunch of them were saying that they were going to implement these ideas and some of them have written to us and talked about how they have adapted the ideas in their own schools. That’s been really rewarding to see. And we’ve heard that people have used it in teacher education classes that they’re teaching. We see a lot of people accessing the companion site for the book as well.

So I know that the book is geared towards K-12 contexts, but are there ways that you could see these concepts implemented at USF?

Definitely. One of my favorite examples is in the family engagement chapter of something that Oakland International High School does, which is the school that I started doing research at in 2014, and is the alma mater of one of the co-authors, Gaby Martinez, who is also a staff member at USF.

Oakland International does something called community walks. They have a professional development day where the kids are not at school, but different groups of students lead an entire day of activities aimed to help educators understand the different cultural groups at the school.

The staff and the teachers are the participants on the walk. And as a researcher at the school, I went on a few walks too. So for example, I went on the one that was planned by students from Guatemala and their families. We learned that a bunch of the kids who are from Guatemala, when school is not in session, or even sometimes when school is in session, will work as day laborers to make money. So we went to a gas station where they try to pick up work and learn about how scary that is to get in a car of a random person and not know exactly what’s going to happen . . . but [they] are desperate and need that money to make the rent or to get food.

Then we went to a church that was run by one of the student’s fathers who was the pastor. It was a church for the Indigenous Mam-speaking Guatemalan community, a lot of whom live in East Oakland. Then we went to a restaurant and ate Guatemalan food. So the community walks . . . are a day where you go to different venues of importance for that community and then you end up back at the school to debrief about how to serve those students better. I think that’s a really cool example of what the school is doing and what we could do more at USF. It’s harder here because students come from all over. But I do think with the requirement of community-engaged learning and getting out into the community, at least learning about the communities that surround us is great and figuring out ways to learn more about the students and where they come from is always a valuable way to engage in the classroom.

You already said you’re teaching, but is there anything you’re particularly excited to discuss with students?

This semester, I’m teaching a class on immigration and education and we’re talking about a lot of things that are in this book. There’s always so much with immigration to talk about. There’s the current border crisis and debates that are happening. There’s historical immigration and thinking about who had an easy time getting to this country and who didn’t. I was just listening to the radio this morning and globally, there are similar issues. They were talking about an Oscar-nominated film about Senegalese immigrants who are trying to get to Italy and how many boats and migrants die en route to Europe. There’s just so many conversations to be had about migration from all those vantage points and where that intersects with education in schools.

I’d now like to turn to your other recent work, The World Yearbook of Education. Can you describe this project for us?

This is an edited book entitled the World Yearbook of Education 2023: Racialization and Educational Inequality in Global Perspective that came out about a year ago. The other book had a lot of contributing authors, but it had a cohesive conceptualization by us from the beginning to the end. Whereas the World Yearbook of Education is a book series that has been around since the mid-1960s in the field of International comparative education. This book series started as a way to focus on a topic every year and then have different contributors from around the world offer examples on that topic for that year. Previous topics have been on the expansion of schooling for formerly colonized countries or governance or funding or participation or girls’ schooling.

Different authors from around the world would contribute ideas in their chapters. A couple of years ago, the editors who ran the series, in light of George Floyd and all the “racial reckoning,” realized that there had never been a volume of the World Yearbook of Education on race, racism and racialization around the world as it pertains to education.

So they asked me and a professor who teaches at UC Berkeley to co-edit a volume. We curated about 35 authors in total that contributed to the book and the chapters include topics such as race, racialization and social movements in Brazil, affirmative action in the U.S., Brazil, and India, the Black Lives Matter at School movement in the U.S., and the racialization of refugees. It’s meant to be a first volume that demonstrates the importance of this topic for the field of international and comparative education and lays out some questions that people could use as a way to further develop research in this area. It was more definitely in the scholarly realm and it’s not going to be picked up by teachers like the other book, but it was a way to mark this topic as important for scholars and it is important that the series acknowledges this topic. We hope that students will orient their research and develop this area of scholarship in the future.

Please tell us about the open access journal you started and run yourself.

Actually, CRASE gets credit for this because I got to know Shawn Calhoun from the library during committee meetings for the first advisory committee that formed CRASE. At the time, I had just come to USF to direct this new master’s program that was starting in our department on human rights education. And at that time, there was no academic journal in the field for people to publish research on human rights education. So people would have to submit to other journals and the academic reviewers would often say, “What is this field? Why are you talking about it?” It was just hard for people to get their work in this field published. I had been thinking it would be great to have a journal, especially an online, open-access one so the work wouldn’t be behind a paywall. I had started investigating open access journals and all I could find online were journals where the person submitting has to pay and the fee subsidizes the platform to allow you on it. I was in this conundrum thinking, if you’re sitting in, say the Congo, and you have to pay $5 USD to submit an article that may or may not get accepted, that doesn’t seem to make any sense.

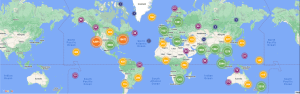

I think I just happened to mention it to Shawn in passing, maybe chatting before a meeting, and he told me that Gleeson Library hosts open access journals. I had no idea. And then he connected me to the person at Gleeson who had been hired to be in charge of open access journals hosted on the platform. We were the second journal that the library launched, the International Journal of Human Rights Education, and we’ve been around since 2017. We have an issue that comes out every year that’s peer-reviewed, online, and open-access. It’s academically rigorous, but open access and online for anyone in the world to download our articles and we’re about to publish Volume Eight. Since 2017, contributions to the journal have been downloaded more than 60,000 times from 186 countries from 2,992 distinct institutions.

When you look at the map here on our journal site, it will show you all the places that have downloaded the journal. It’s kind of cool because usually when you think of academic scholarship, often you only see people in the Global North able to access it, but our journal is reaching people all over the world.

I wouldn’t have known about this program had I not been on the CRASE advisory board and had that offhand conversation with Shawn. We’ve had a few special issues that are curated around a theme (like Indigenous women and human rights education or human rights education and Black liberation), but other than that, it’s just been word of mouth in terms of how people learn about our journal. We don’t have any budget. It’s a bunch of volunteer doctoral students and me engaging in this labor of love every year and putting together the issues.

Wow, that’s amazing! Lastly, are there any upcoming projects on the horizon?

We’re working on Volume Eight of the journal and it’s always a slog to get the new issue out. We’ve got six articles, four commentary pieces, and five book reviews coming out. Both of the books we talked about earlier came out at the same time last year, in 2023, so I’m still being invited to do a lot of talks, presentations, and teacher professional development.

During the COVID shutdown time, my kiddo was schooling from home and we were able to get a glimpse into his schoolwork and curriculum. He was in first and second grade at that time. His teacher was teaching the class about the origin of kites from China, and I was thinking about how in India, where my family is from, we have kite-flying festivals, and I just went down a rabbit hole learning about the origin and use of kites around the world. I drafted a children’s book manuscript about it and got a lot of rejections, and rewrote the book probably ten times. It was finally acquired last year by Bloomsbury children’s publishing, and I’m working on final edits right now. The book that will come out in 2025 is called “A Year of Kites” and it talks about kite traditions from around the world. I’m excited about taking messages of peace, human rights, and global understanding to younger audiences with this project.

Thank you so much!

What a great journey combining the many experiences into your books and spreading an important message keep up the good work!!

Amazing work Dr. Bajaj! A true innovator with great intention, focus and hard-work. Thank you for continuing to make space in the world for these important topics- especially for setting a teaching standard for refugee students in our US school systems.

Wow, what an inspiring journey! It’s incredible how a simple moment during the pandemic turned into such a meaningful project. “A Year of Kites” sounds like a beautiful way to connect children with global cultures and traditions, and it’s so refreshing to see stories that promote peace and understanding at an early age. level devil