During this closing reception, USF faculty responded to Limning the Liminal by Jenifer Wofford, which ranged in subject matter, from Filipina nurses, WWII comfort women, to the aftermath of Pacific Rim earthquakes. Perspectives incorporate personal history and stories, scholarly analysis, and creative expression. Presenters included Professors Monisha Bajaj (International and Multicultural Education), Omar Miranda (English), Dean Rader (English), Evelyn Rodriguez (Sociology), and Ronald Sundstrom (Philosophy).

During this closing reception, USF faculty responded to Limning the Liminal by Jenifer Wofford, which ranged in subject matter, from Filipina nurses, WWII comfort women, to the aftermath of Pacific Rim earthquakes. Perspectives incorporate personal history and stories, scholarly analysis, and creative expression. Presenters included Professors Monisha Bajaj (International and Multicultural Education), Omar Miranda (English), Dean Rader (English), Evelyn Rodriguez (Sociology), and Ronald Sundstrom (Philosophy).

Author: craseadmin

Going Public with It: Blogging for Social Justice

In this March faculty workshop, Huffington Post blogger and USF Professor Rick Ayers shared writing prompts and exercises to discuss scholarly interests in the format of a blog post. During the two-hour session, faculty received plenty of tips and had time to brainstorm, develop ideas, and begin writing. Participants worked in small groups to receive feedback and refine ideas.

Read more about blog writing in Rick Ayers’s “How to come up with an interesting and meaningful blog post or public scholarship.”

Manuel Pastor in Conversation with Marisa Lagos: What the Bay Area Tells us about America’s Hopeful Future

CRASE and the Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good welcomed Manuel Pastor, author of State of Resistance: What California’s Dizzying Descent and Remarkable Resurgence Mean for America’s Future, to discuss his book and respond to the CRASE blog issue “Bright Future or Cautionary Tale? How the Bay Area Shapes the Future of the U.S.” where faculty across the university discuss recent social, legal, technological and environmental transformations in the Bay Area, some of which represent progress and others that signal deeper challenges moving forward. During this event, Pastor spoke with KQED’s Marisa Lagos about his book, current issues facing the Bay Area, his optimism about the future of California and the nation, and ways to bring about continued change.

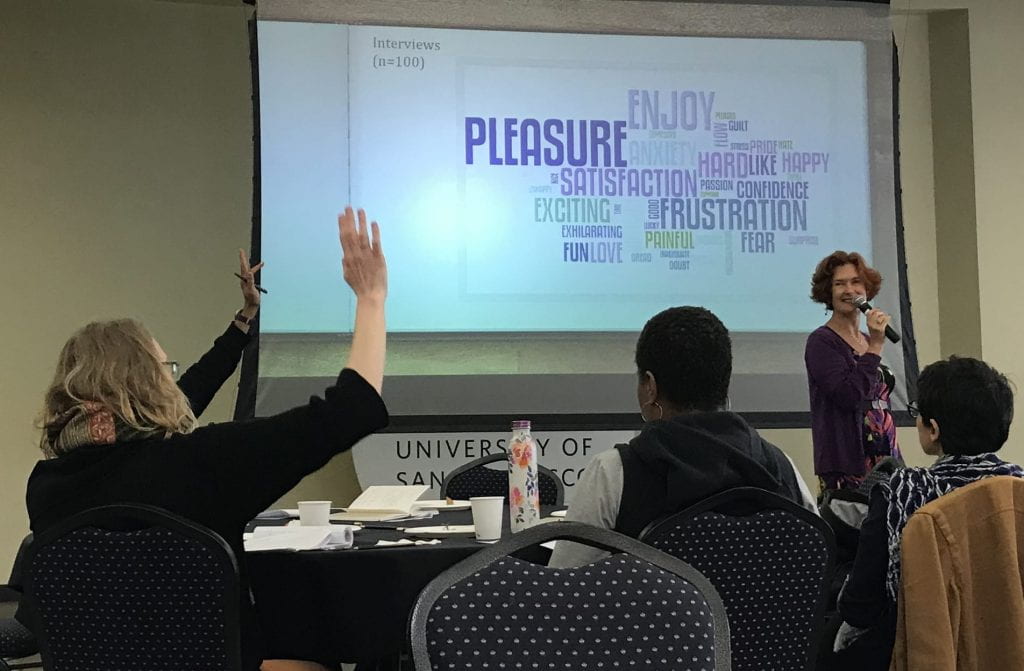

Helen Sword: Writing with Pleasure

Over twenty faculty participated in this February workshop for academic writers who aspired to bring more “air & light & time & space” into their own writing practice. Helen Sword made an evidence-based case for recuperating pleasure as a legitimate (and indeed crucial) academic emotion. Sword encouraged participants to think about objects, places, and aspects of writing that brings joy to faculty and provided resources to analyze writing style and behavior.

Participants found it helpful to hear about the writing process from a different perspective and reflected on their own writing habits in a new way.

Guantánamo’s Legacy

Photo by Alex G.

Today is the 17th anniversary of the opening of the Guantánamo Bay detention center in Cuba. Seven hundred and eighty Muslim men and boys were held in the prison. Many were held for a decade or longer, and nearly all were held without charges. Forty men still languish in the prison, with no possibility for exit. President Trump has stated that he has no interest in shuttering the prison. Instead, he has suggested that he would like to “load it up with some bad dudes.”

The Guantánamo detention center has not been in most people’s consciousness through the seventeen years that it has been open. In fact, when President Obama said on his second day in office that he would close the prison within one year, many people thought he did. He never did.

People today may believe that the men held in Guantánamo were “guilty.” However, hardly any of them were ever charged with a crime, and nearly all of the men were released without charges. America’s foundational belief in due process and the rule of law did not protect these men from being held in Guantánamo without charges. Nor did it protect them from torture. The rule of law also did not matter when the U.S. military purchased some of the men who were later held in Guantánamo—by paying bounties to Afghan and Pakistani soldiers. A British lawyer described these purchases as a modern-day slave trade.

Of the forty men remaining in the prison, six “high value prisoners” are to be tried in military commissions. Preliminary proceedings have been ongoing for more than a dozen years, and there is no indication that these six will ever have a trial. If they die before their trials are concluded and verdicts are given, we will never have the rule of law assurances that the men were guilty of their alleged crimes.

Violating the rule of law in Guantánamo extended beyond subjecting the men to torture and holding most of them for years without charges. Defense lawyers found microphones in client-meeting rooms in the prison. The lawyers also discovered that officials had read the prisoners’ legal mail.

The Periodic Review Board—the panel that reviews the status of the men in Guantanamo—has not recommended release of any prisoner since Trump took office. Five of the men currently held in the prison were cleared for release during Obama’s tenure. However, they were not released before Trump assumed office, and Trump has no interest in releasing them now.

The rule of law was broken in Guantánamo. It continues to be broken today—in Guantánamo and in the culture of the current administration. Producing the Muslim ban; blocking families from lawfully applying for asylum; separating children from parents at the border; directing illegal campaign payments; unilaterally withdrawing from treaties; ridiculing federal judges; and pursuing policies that benefit the president’s business dealings; all reflect that the president is not committed to guaranteeing that our laws be faithfully executed, as he solemnly swore under oath.

With the Democrats winning the House in November, there is hope we may return to civility and the rule of law. But, we cannot fully return until we also recognize the damage to America’s principles and values caused by our continued actions in Guantánamo.

Someday, Guantánamo may fade from our lives and our memories. But, today we must publicly acknowledge that Guantánamo was wrong and unlawful, that the rule of law is inviolate, and that this and every administration must strive to faithfully execute the laws and uphold the Constitution.

Professor Peter Jan Honigsberg is Founder and Director of Witness to Guantánamo and author of books and articles on post 9/11 issues. His latest book will be published by Beacon Press in fall 2019.

Faculty Spotlight: Michelle Millar

Michelle Millar lived in Las Vegas while working on her Ph.D. in Hospitality Administration. During our conversation, we discussed sustainability and greening in the hotel industry, the relationship between academia and industry, and her recent research.

How did you first become interested in sustainability?

I grew up conserving because we had to, which is the case for a lot of people, but I really began to focus on sustainability after I took a trip to Costa Rica and stayed in an ecolodge. I didn’t go with a research agenda, but I came away with a completely different perspective of what travel could be. Since the ecolodge was such a tiny place, I was able to meet other people from around the world. One couple was very conscientious about the environment and their impact on it, and they really struggled with the fact that they flew from England on a really long flight to get to this place that is so caring for our environment. That thought stuck with me.

What I quickly learned was that, in the hotel industry it is referred to as “greening” the industry, not ecotourism, which really implies only environmental awareness. Sustainability is bigger, however—it’s about the planet, it’s people, and also making a profit—yet very few people were approaching it that way in the hotel industry-related research. Sustainability is a concept that changes depending on who is giving you the definition. When I started my research in the greening part of sustainability, no one else was doing it. It’s evolved, fortunately, and has become more popular in our industry and in research

After that trip to Costa Rica, I started digging into the literature about ecotourism, but because the ecotourism world is so vast, I honed in on hotels and what they can do in terms of being green—what they can take from an ecolodge like the one I visited and bring to everyday hotel life. It started with what consumers want in a green hotel and a green hotel room. Do they want low-flow water shower heads and/or dispensers in the room instead of individual amenities? Do they want recycling? Do they care about whether the sheets are organic or bamboo? I ended up with a model that identified what consumers would be willing to stay in and pay for since there’s often an extra cost for a greener hotel—or at least there is a perception that there is an extra cost.

Describe your recent work.

I teach classes in the Hospitality Management program about managing meetings and events. I’ve written two papers about whether or not hospitality industry managers want students to learn about sustainability in college. The interest has grown exponentially in the past few years as colleges offer degrees in meeting and event management. I’m trying to understand what the industry wants from our students in terms of sustainability and if they even believe it’s a skill students should have. We can then report to schools that this is what the industry believes is important to know in terms of sustainability and keep our curriculum relevant.

What was it like switching from the hospitality industry over to academia?

I was a travel agent for sixteen years, and I came to a point where I was ready for a change and decided I would go get my Ph.D. I had a friend who was a professor who told me to go for it, and if I didn’t like it, then I could do something different afterwards. I loved it, especially the teaching and would never have thought I would be going in this direction in my life. For me, it was a pretty easy transition going back to school, partly because I didn’t know what I was getting myself into, but actually earning the Ph.D. was the hardest thing I had ever done.

I lived in Las Vegas for five years when I did my Ph.D., and the industry down there is effective at conserving for cost savings. For example, in Las Vegas, they recycle all water—the water you see in the fountains in Vegas comes from reclaimed water. They’re taking water from the laundry and cleaning it to a certain degree and putting it back to the fountains. You can’t drink it but you can use it. The gaming industry of Vegas uses less water than the entire community of Las Vegas because of water-saving measures. Their laundry facilities are state-of-the-art and use less power. Some properties have their own electrical co-generation plant or they have solar panels in the desert that they draw from. On the Vegas Strip, many of the larger properties have people in the back sorting trash. Another example of how the Las Vegas community attempts to conserve is through farming. There is a pig farm outside Las Vegas where all the food waste goes to feed the pigs. Then the farm sells the pigs back to the industry to use locally. All of these practices opened my eyes further to the role that sustainability can play in the industry—and it was Las Vegas!

When you initially started down this track, were you always very conscious that you wanted your research to be applicable to industry?

I did because the hospitality industry isn’t going to change the world in terms of research—it has to be applied—and that’s why it became important for me. Since I came from the industry, it was very important for me to have the connection between the two because industry doesn’t necessarily read our research journals, but I can share research with them via other avenues. It’s a good way for me to maintain the connection to industry.

I’m involved in industry associations such as the Green Meeting Industry Council. Being an educator on that committee allows me to share what we’re doing in academia and in hospitality and sustainability. The people in that association are executives or they own their own meeting/planning company, but they’re all in it because they care about the environment. An association such as the Club Managers Association of America is completely unrelated to sustainability, but being a part of it affords me the opportunity to talk to managers of golf clubs and country clubs about sustainability about what they can do and what they need from us in terms of research. Those are important avenues to reach the industry.

How do you bring your knowledge of industry and research into your courses?

The industry part is easy because students like to hear your experiences in it. So whoever you are, if you’ve worked and you teach, you can marry the two easily. For me, it’s more about sharing that I have a passion for sustainability. There aren’t just one or two lectures devoted to it, it’s infused throughout from Day 1. I can bring it into my classes and say that this is what I’ve found or this is what the industry believes you should know about sustainability.

Do students have a passion for learning more about these things, too?

Over the past seven years, the interest is rising. Students recognize the ethical side of this work. I have definitely seen a change with this generation—they do seem to care and they want to make choices that incorporate that ideal. San Francisco in particular is exceptional. Some of my students are from different parts of the U.S. and the world, and they understand that we’re uber-exposed to issues of sustainability here. It’s not the norm, however, and they recognize that when they go home they have the opportunity to educate others about these ideals.

What brought you to USF?

They had a job posting for a hospitality professor with a research focus on sustainability. It was very specific, and I felt it was written for me. All my friends who saw the posting told me I needed to apply. I grew up in Concord, California but lived in other parts of the U.S. for several years, so this job brought me back home.

I didn’t know about USF growing up, so even when I applied for the job, I didn’t know a lot about this campus. Reading about USF and teaching to the whole person resonated with me. When I came here for a pre-interview, I really hit it off with the Deans of the program and the faculty. All of that clicked together, and here I am today!

Academic Freedom in Dangerous Times: A Panel Discussion

This event, co-sponsored by the Tracy Seeley Center for Teaching Excellence and the Center for Research, Artistic and Scholarly Excellence, was moderated by Michael Rozendal (Rhetoric and Language) and featured Aysha Hidayatullah (Theology and Religious Studies), Brandi Lawless (Communications), and Stephen Zunes (Politics). The conversation focused on current issues in academic freedom and experiences online and on campus. Topics included the history of issues encountered at the University of San Francisco, university procedures and policy, discussing issues with students, and future developments.

Over 35 faculty and staff members attended this event. Afterward, CRASE created an interdisciplinary action group grant Academic Risk and Freedom in Dangerous Times a forum is planned on October 22, 2019

Faculty Spotlight: Rachel Brahinsky

Rachel Brahinksy began her career as a Bay Area reporter. During our conversation, we talked about her research, historical geography, and how San Francisco has changed over the years.

How did you first become interested in research?

Before I did my Ph.D., I was a journalist. I was always curious and wanted to find the stories that weren’t being told. Before that, in college, I took a lot of African American Literature classes, which opened up this narrative that was absolutely outside of the standard history that I had been taught. Experiences like that set me down the road of trying to find more of those stories. There’s a multiplicity of narratives and lives and relationships. The power dynamics at play, and how things are written, is really important.

How did you start with journalism?

I always wanted to write. When I was working on my undergraduate thesis my writing professor thought I was too political, and my politics professors wanted me to get away from the storytelling. I wanted both and thought both were possible. I went off and got an internship at The Valley Advocate, which is a lot like The Village Voice, The Bay Guardian, or City Paper, and did that for about a year. Then I came here for an internship at The Bay Guardian and was a reporter there for 5 years.

How did you transition from journalism to your Ph.D.?

I had repetitive strain in my arms from typing really fast all the time, which is what you do when you’re a reporter, so I went through a round of physical therapy to deal with that. I came out of that process a lot better physically but realized that it wasn’t sustainable for me to be at a desk in a stressed-out position all day long.

I wanted a different pace, and teaching was something I was always interested in. Ultimately, I was trained as a human/critical geographer. That does mean certain things about how I understand what matters and what to look for in research, but my work is very interdisciplinary. I bring history, urban planning, ethnic studies, African American studies, and a little bit of gender studies together in a geographical frame.

What are you working on now?

My primary book project evolved out of my dissertation, which was called “The Making and Unmaking of Southern San Francisco.” It was a story about Bayview Hunter’s Point, race, redevelopment, and industrial land use—and how all of those things fit together over the course of about 100 years, so it covers a long historical geography. I’m expanding that and the working title is Race in the City: A Story of Property. It’s a book about the way that race fits into those categories of property and ownership, how race and space make each other, and how urban change and urban development can help us understand both how race and racism are created and re-formed, and also how to deconstruct them. It’s a story of urban development and fights over social justice and urban planning.

I also have a collaborative book that is called A People’s Guide to the San Francisco Bay Area. It’s a social and political history of the Bay Area, mostly focused on social-movement histories in the form of a scholarly guidebook. We take you to lots of sites and tell stories about social movement histories that intersect with that place. It builds out of an urban field class that I teach at USF where we walk around different neighborhoods and I teach students about landscape theory and the history and politics of place.

Is there a story that really resonated with you?

When I was doing research on the Fillmore District and thinking about the intersecting displacement of African American and Japanese American communities, I came across this about this group of women in Bayview. People would say “If we had the Big Five around, things would be different—they knew what they were doing.” And I was like: what’s the Big Five? I ended up studying them—there were more than five of them, it turned out, and the people included in the group changed over time. It was an evolving organization. They were African American women who were struggling economically and financially in Bayview, and they saw what had happened in the Fillmore where twenty square blocks were razed to the ground by the redevelopment agency, with people displaced from their homes and businesses.

At the time, Bayview was covered with temporary war housing. It was never meant to be permanent, and about 20 years later it was falling apart. The redevelopment agency turned to Bayview and started making plans for clearance and development there. The Big Five went down to various meetings and said: “If you want to develop in Bayview, you have to come through us.” They persisted, and they became part of the redevelopment process. Bayview Hill was actually remade actually quite beautifully. The vision people have of Bayview now is distorted by time, but when housing was first remade on Bayview Hill with little cul-de-sacs, it was quaint and cute and welcoming. The streets are all named after these women, so you’ll see their names all around the hill: Eloise Westbrook, Marcelee Cashmere, etc.

But there was not really an economic development plan that came with the housing development plan, so Bayview continued to struggle, even though people were happy to be living in this brand-new housing. The end of the story is challenging, but there was this moment of about 15 years where community members were figuring out how to turn resources toward the community and learning how to work together to organize. There were challenges, but these women were what some people call street scholars, and they learned all the language of urban planning “setbacks” and “maximum heights.” They taught it to themselves and each other and they went down to the meetings and they said this is what we need in our neighborhood. And they kept doing it, and sometimes they would get hired. That gets complicated. Some people said they sold out because they were willing to become part of the agency, but what they won for the community was very significant. It was a small community effort where people learned from other neighborhoods and were really able to make a difference, for a moment.

How do you bring your research into the classroom?

My research shows up in the material through lectures, and sometimes a student will ask a very innocent question, which kind of sparks me to think, “I don’t know the answer and I need to go figure that out,” and it sends me down some new research paths. I find the teaching process really fun in that way. Ultimately, I want my students to leave with the capacity and curiosity to keep asking questions and to see that as an integral part of their lives.

Do you have a moment when a student asked you a question and it guided your research?

A couple of years ago I had students reading a book by Neil Smith, a classic book on gentrification. The question that came out was “what comes next after gentrification?” In some ways it’s simple—of course we don’t know what’s next, but when you’re studying cycles of urban change, you need to think about the patterns of the past and what they may be turning in to, as we study them. And there was something about the simplicity of that question that sent me down this research path, hoping to clarify the language I use when I teach about the changing city. There’s always something new to understand.

CRASE Pecha Kucha

During this event, faculty presenters talked about their scholarly work in a highly visual and fast-paced Pecha Kucha style. Over fifty people attended the event on Thursday, September 6, 2018.

Byron Au Yong from Performing Arts and Social Justice, College of Arts and Sciences presented his recent work as a composer including Kindnapping Water: Bottled Operas and Stuck Elevator.

Lara Bazelon of School of Law shared the story of her recently published book Rectify: The Power of Restorative Justice After Wrongful Conviction.

Alessandra Cassar in Economics, College of Arts and Sciences challenged the idea that women are less competitive than men.

Barbara Sattler of the Masters in Public Health Program, School of Nursing and Health Professions discussed climate change and the Global Climate Action Summit.

Sumer Seiki in Teacher Education, School of Education shared projects to make science education more equitable.

Aparna Venkatesan in Physics and Astronomy, College of Arts and Sciences presented on elements that allow astronomers to study stars and galaxies.

Neil Walshe in Organization, Leadership and Communication, School of Management shared personal research on the Irish War of Independence.

Japantown Writing Retreat

CRASE offered a writing retreat for full-time faculty to get a head start on their summer writing at the Hotel Kabuki in San Francisco Japantown. This was an opportunity for faculty to reflect on their writing process, develop a strategy for tackling their summer writing goals, and make progress on their writing. Each faculty member had the opportunity to share their writing goals for the summer and made substantial progress on a range of writing projects from articles to chapters to book proposals. Faculty discussed their projects and research with their colleagues and had time to socialize over shared meals.