Before going to law school, Julie Nice worked as a domestic violence advocate. During our conversation, we discussed the importance of telling the stories behind cases, the interdisciplinary nature of poverty law, and how her students inspire her.

How did you become interested in law?

When I was an undergraduate, I studied rhetoric at Northwestern, and I was fascinated by the power of words, the power of arguments, not just the process of persuasion, but also words as articulations of ideals and values. Law reflects and relies on the power of language. After all, the only way for courts to maintain legitimacy is to convey their reasoning in a way that is sufficiently persuasive to the public.

After my undergraduate education, I worked the overnight shift at a domestic violence shelter in inner city Chicago. I saw the inability to attack injustices without the credentials and credibility that come from knowing the language of the legal system. Nobody listened to me when I was a domestic violence advocate. My legal education enabled me to translate the stories of victims of domestic violence in a way that the system could understand. I always remind my students that you need to become proficient in the language of law, rights, and legal argumentation but you should never lose sight of the human story you’re trying to convey.

I represented mostly impoverished clients in Chicago, and I saw first-hand how the legal system completely and generally disregarded them. I had so many clients that at the end of the hearing—before we knew if we had won or lost—often said, “Thank you for telling my story.” What mattered to them was that the system heard their story. Just being heard by the system affirmed their dignity.

What are you working on now?

I’m comparing how the law regulates human sexuality and how the law regulates poverty and poor people. Within constitutional law, the government must, at the minimum, have a rational basis for how it regulates us all, meaning the government’s means must be rationally related to serving some legitimate ends. It usually takes some concerted effort by constitutional lawyers to teach legislators and judges to see the irrationality behind many of our cultural assumptions and prejudices.

We’ve made some progress in the past several decades in reproductive rights and LGBTQ rights in having legislation and judicial decisions that recognize that governmental policies regulating human sexuality have to at least be rational. If you’re going to ban same-sex marriage, what’s your reason, what are you trying to achieve? You need something that you can say the policy is at least rationally related to. After twenty-five years of same-sex marriage litigation, it became clear that the government simply wasn’t able to defend the rationality of banning same-sex marriage.

At the same time, we’ve made almost no progress in getting legislators or judges to even think about whether the way we treat poor people is rationally based. The truth is that legislators and judges mostly think that whatever we do that denigrates or penalizes a person who is receiving welfare benefits might motivate them to go get a job, so they won’t be on welfare anymore. As this thinking goes, anything we do to poor people is rationally related to making them pull themselves up by their bootstraps and magically become not poor. This overarching ideology justifies our harsh and discriminatory treatment of poor people.

How do we change that narrative?

I have to say that I don’t really see much of a change happening, and one of the greatest disappointments for me is that I haven’t been more successful in helping to produce a meaningful dialogue about what economic conditions and system might be just. It is extremely difficult to get assumptions about class onto the radar screen and to get someone to see their own assumptions and examine whether these assumptions are rational.

The current cohort of undergrad and grad students are my inspiration because the inquiry and exploration I’m trying to do—both with my students and in my research—are speaking to the future, which really is in the hands of the people in the classrooms now. There is a glimmer of hope that this generation gets it more than prior generations have. It’s truly where I get my daily inspiration.

Are the discourses changing in poverty law?

In the late 1960’s, there was a spike of interest in how the law treated poor people, and a few poverty law textbooks were written. With the rise of conservatism in the 1970s and 1980s, however, these textbooks went out of print and poverty law was almost entirely extinguished in law schools.

When I started teaching at Northwestern law school in 1989, some students came to me and said, “We want to learn about poverty and law.” So I put together a set of teaching materials that were published as a new poverty law textbook. I am proud of helping to revive the field of poverty law, and there are now several textbooks and a lot of critical class scholars doing legal scholarship on issues of poverty law across the academy. Those young scholars also give me a lot of hope.

Those of us who do poverty law rely on people from various disciplines. I need economists and sociologists and political scientists and anthropologists. I use so much material from other disciplines to explain what is happening with regard to economic injustice right now. Then the question will be what do we want to do about economic injustice. We have to start by identifying the assumptions underlying our economic policies and considering whether those assumptions are rationally supported by data. But it takes political will to comit to conducting this analysis. It’s very much about politics.

Your students really do inspire you and give you hope. How do you bring this research and knowledge to them?

I work with each individual student on their interests and their career objectives and try to see how the student’s own interests and objectives intersect and interact with the subject matter. Whether they’re interested in intellectual property, tax law, estates and trust, family law, employment law, housing law, or criminal law—all of those things have implications related to economic justice. It takes a lot of one-on-one time, but I haven’t found any short cut that gets us to that genuinely engaged inquiry that creates educational magic.

I do find that real stories help to create that educational magic. I recently uncovered one family’s story behind the famous constitutional law case that established the precedent that courts do not have to look carefully at how the government treats poor people. In this case from 1970, Dandridge v. Williams, the United States Supreme Court said it wasn’t interested in hearing about how poor people might think they’re being treated in an unconstitutional way. The court basically said, “We’re hoping to keep these cases out of court; we really don’t want to hear them.” It’s a very famous case. The parents that brought this case were married parents of eight children, and the state of Maryland was giving their family of ten the same amount of welfare to live on as a family of two. The Supreme Court said the government’s policy might look harsh but it’s okay because it’s welfare and the states basically can do whatever they want to motivate families to get off welfare.

As part of this book project, we were getting the backstory of famous poverty law cases that were constitutionally based. The parents who brought this lawsuit had already died, but I found the grown children of that family, interviewed them, and discovered the real story of how that family had survived with their father and mother both disabled. The father took on work at a chicken farm and worked long hours when he was able, and he brought home chicken feet that the mother would use to create meals for this family of ten. The children regularly went without meals and without heat, but the parents somehow managed to keep the family together. Unfortunately, you won’t find their story in the Supreme Court’s decision. The Court never grappled with the reality of this familiy’s struggle to survive. I was deeply affected by the family’s real story and thought it needed to be told.

I find that students are inspired by learning the real stories of people involved in Supreme Court cases. Most of the human aspect is long gone by the time the case has made its way all the way up to the Supreme Court, but students really connect with understanding how constitutional issues affect people’s lives. In the end, law is always about the human story. How law affects our lives is what justice is all about.

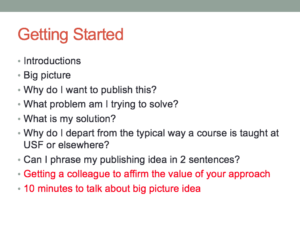

This workshop was designed for faculty who are familiar with qualitative research, through graduate school or from previous research experience, but need a refresher on key concepts and the latest data collection and data analysis methods. We discussed what methods to use based on your project question, goals and research paradigm. Some of the qualitative approaches discussed and compared include: ethnography, case study, interviewing, grounded theory/open coding, discourse analysis, narrative analysis, and CBPR/PAR. Professor Evelyn Ho has taught qualitative research and led numerous interdisciplinary projects using qualitative methods.

This workshop was designed for faculty who are familiar with qualitative research, through graduate school or from previous research experience, but need a refresher on key concepts and the latest data collection and data analysis methods. We discussed what methods to use based on your project question, goals and research paradigm. Some of the qualitative approaches discussed and compared include: ethnography, case study, interviewing, grounded theory/open coding, discourse analysis, narrative analysis, and CBPR/PAR. Professor Evelyn Ho has taught qualitative research and led numerous interdisciplinary projects using qualitative methods.

In this workshop, Huffington Post blogger and USF Associate Professor Rick Ayers (Teacher Education) shared writing prompts and exercises to connect with readers and promote extended public discourse in crucial issues. During the two-hour session, faculty writers brainstormed and drafted ideas and worked in pairs to refine their blog ideas. Participants felt that Ayers led a productive writing session and had useful advice on developing their voice.

In this workshop, Huffington Post blogger and USF Associate Professor Rick Ayers (Teacher Education) shared writing prompts and exercises to connect with readers and promote extended public discourse in crucial issues. During the two-hour session, faculty writers brainstormed and drafted ideas and worked in pairs to refine their blog ideas. Participants felt that Ayers led a productive writing session and had useful advice on developing their voice.