Sergio De La Torre, Associate Professor of Fine Arts in the Department of Art + Architecture at USF, was recently awarded the Art for Justice Fund grant for $100,000. The fund is focused on supporting and promoting art projects that take on the prison industrial complex in the United States. Awardees are nominated from a large pool of individual artists and artists’ collectives working in the United States.

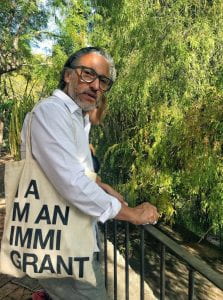

Prof. De La Torre was nominated for the remarkable work of his Sanctuary City Project, which investigates the actions of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the implications of border arrests, and the emergence of private detention centers. Using art that includes print-making, banners, billboards, photography, and video, Prof. De La Torre’s goal is to reveal the hidden and not-so-hidden motivations behind the U.S. government’s punitive actions in the sphere of immigration and the space of the U.S – Mexico border.

In our conversation, Prof. De La Torre talked about the award, his work, and future projects.

Tell us how you received the award and your reaction on learning about it?

When I received the award, I got an email in March 2022 from a person saying that they were looking for Sergio De La Torre because he, that is I, had received an Art for Justice Fund award. At first, I thought this was a phishing email. Is this real? The email sender then said that if I don’t believe him, I should check my spam folder. I did, and there it was, in my USF email spam folder where it said I had received an award from the Art for Justice Fund in the amount of $100,000. I was absolutely elated!

Going back, can you tell us how you got into art, or became an artist?

That’s another funny story. I finished high school in Mexico when I was 17 years old. I was born in San Diego and so was an U.S. citizen living in Mexico. At 18, in Mexico, you have to decide which citizenship you are going to pick (back then, 1984, there was no dual citizenship) and so I picked the U.S. I never saw myself living in the United States and therefore was kind of surprised that I picked U.S. citizenship. I couldn’t continue studying in Mexico as a national but had to continue as a foreigner and with tuition very high, I didn’t go to school for three years. I had to then establish residency in the U.S., which is when I started working in San Diego. During this time, I took ESL classes, and got thoroughly bored. A friend of mine said, “study art because you don’t need to speak English.” And that’s how I got into photography, painting, design, drawing, and printmaking at the Southwestern College in Chula Vista.

The art teachers there were part of a collective focused on “border art.” They organized art events – performances, dinner parties, conversations – and had branched out into these other forms in contrast to traditional drawing, painting, and sculpture. Back then, the border didn’t have a wall, it wasn’t militarized, and was far more fluid (that’s where most of the migration from other parts of South and Central America took place, through Tijuana).

During the 1980s, I was not particularly drawn to “border art” or the kind of work my teachers were doing. I didn’t fully understand these forms of art practice and their implications. After coming to San Francisco in the early 90s—I came to study photography at the California College of Arts and Crafts (CCAC)— acquiring some physical distance between myself and the border is what helped me understand my relationship to the border and the art practices around it. Later, I went and got an MFA in Fine Art at UC San Diego where I worked on my film MAQUILAPOLIS that examines the lives of factory workers at the U.S.-Mexico border. The film premiered at the Rotterdam International Film Festival and was received very well.

So, my becoming an artist, and my current practice, owes a lot to my early teachers who were practicing “border art’, in particular Liz Sisco.

What can you tell us about your art practice?

During my arts education, I came to the realization that museums and galleries were no longer at the center for the display and dissemination of art. There were other places that were far more vital for art. That realization changed my practice and made me focus more on process, research, interactions with audiences, talking to subjects, and so on. Subsequently, I turned these immersive and experiential practices into artwork. My work is indeed present in museums and galleries but understanding these processes and practices has informed my work.

What projects are you working on and what are your plans for the future?

An immediate project is to finish a book for the Sanctuary City project. The book will include every phrase we have collected and every poster we have made – about 40 of them – that speak about immigration issues and sanctuary cities. The book will also include data about immigration policy and practice from 1989, when San Francisco became a sanctuary city, to the present. I also have new projects I am working on, in particular about “surveillance ankle monitors” and for that I am working with Mujeres Unidas y Activas (MUA) and the Dreamer Fund. My plan is to interview people that wear these monitors and understand the stigma as well as the emotional and psychological states they go through. I am envisioning an audio installation that expresses these feelings.

Installation of Sanctuary City posters at the Palo Alto Art Center.