As I have written in the past, a lot of attention is currently being paid to the topic of student loan debt in the United States (a couple of representative posts can be found here and here). Earlier this year, President Obama proposed to make community college free for all students, motivated at least in part by concerns over the growing volume of student loan debt in the nation. With the 2016 presidential campaign starting to gear up, there are already indications that student loans will be an important topic of debate.

As I have written in the past, a lot of attention is currently being paid to the topic of student loan debt in the United States (a couple of representative posts can be found here and here). Earlier this year, President Obama proposed to make community college free for all students, motivated at least in part by concerns over the growing volume of student loan debt in the nation. With the 2016 presidential campaign starting to gear up, there are already indications that student loans will be an important topic of debate.

I recently received in my email inbox a request to sign a petition to “forgive all student loan debt” in the country. The email did not come from some fringe group that was an offshoot of the Occupy Movement that first started a few years ago, and included as one of its platforms the elimination of all student loan debt. The email came from the American Federation of Teachers, the second-largest teacher union in the country, representing over 1.6 million members. The AFT, in conjunction with other groups, is calling on President Obama and Congress to wipe out all of the existing $1.3 trillion in loan debt held by current and former college students in the nation.

At first glance, this may seem like a good idea. Much has been written about the growing volume of student loans, and the impact it has had on students and former students. As I have pointed out in earlier posts, however (such as those noted above), much of what the media has written about is grossly exaggerated and focuses on outliers. The vast majority of students are borrowing more reasonable amounts, and while some students do struggle to pay back their loans, this is not a reason why all student loans should be forgiven and future student loans eliminated.

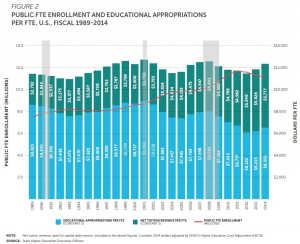

In the ideal world colleges and universities, along with grants and scholarships, would be funded at a level that would not require students to borrow to attend college. But we don’t live in the ideal world. The fact is that states have been disinvesting in the public higher education system over the last dozen years when measured in constant dollars on a per-student basis. The chart below is from the State Higher Education Finance Report for fiscal year 2014, compiled by the State Higher Education Executive Officers association (click the image to see a larger version, then click on the image on the next page).

In FY 2014, per-student state appropriations for higher education were 24 percent below the funding level in 1989. The result, also shown in the chart, is that net tuition revenue (the tuition received by public colleges and universities after grant aid is subtracted) has more than doubled during this period. Considering that three-quarters of all undergraduates are enrolled in public institutions, it’s not surprising that this increase in tuition prices has led to a large increase in student loan borrowing. This relationship between state funding and tuition costs has been well documented by a number of studies, including a recent one by the think tank Demos.

If you look closely at the chart, you’ll see a repeating pattern. Higher education appropriations hit a peak just about as a recession hits the nation, and then decline for a few years following:

Here I have overlaid in gray the durations of the three recessions, as determined by the National Bureau of Economic Research, that have hit the country in the last 25 years. State expenditures tend to lag the onset of recessions, so following each recession, funding for higher education has been decreased for three to four years. As the economy approves, and state revenues increase, funding for higher education tends to rebound.

But there is another important pattern in this figure. Following the recession of 2001, state expenditures never returned to the high point of $8,964 per student before the next recession hit in late 2007. And it’s highly unlikely that as state budgets rebound from the most recent recession – or the “Great Recession,” as some have named it – that higher education funding will return to the 2001 peak.

Thus, students are going to continue to face increasing tuition costs, and will continue to need student loans to help meet those costs. A call for forgiving all student loan debt would presumably also entail getting rid of, or strictly curtailing, future loans as well – otherwise we’d find ourselves in exactly the same situation down the road. Eliminating student loans will not rein in increasing prices; tuition prices have continued to rise even as federal loan limits have not. In a report I wrote for the American Council on Education, I demonstrated that there is little, if any, empirical evidence for the “Bennett Hypothesis,” the argument that federal student loans lead to increased tuition prices.

Reasonable amounts of student loan borrowing are well worth the investment of attaining a college degree. Eliminating all student loans will only lead to restricting access to college for first-generation students and those from moderate-income families who need assistance in paying for their postsecondary education.