As I have written in the past, The New York Times has had a pattern of sensationalizing the status of student loan debt in the country through a series of articles that misrepresent the true status of borrowing. It is a mystery to me why the Times persists in doing so, as they have also published articles that more accurately show the true state of affairs. The most recent misrepresentation appeared last week in an article authored by Kevin Carey, a frequent critic of higher education in this country. Earlier this year I wrote a critique of Carey’s most recent book, The End of College.

As I have written in the past, The New York Times has had a pattern of sensationalizing the status of student loan debt in the country through a series of articles that misrepresent the true status of borrowing. It is a mystery to me why the Times persists in doing so, as they have also published articles that more accurately show the true state of affairs. The most recent misrepresentation appeared last week in an article authored by Kevin Carey, a frequent critic of higher education in this country. Earlier this year I wrote a critique of Carey’s most recent book, The End of College.

In his Times article Carey tells the story of Liz Kelley, a 48-year-old woman who borrowed $26,278 to earn a bachelor’s degree in English in 1994, but whose student loan debt today totals $410,000 – yes, $410,000! As Carey points out, this is a sum of money Ms. Kelley is unlikely to be able to ever pay back given her current career as a teacher at a parochial school. Her total borrowing ballooned because of additional debt she took on for graduate programs (in law, which she didn’t complete, and then education), and the fact that she was infrequently, if at all, actively repaying her loans.

Carey notes that $410,000 is a “staggering and unusual sum,” as if to signal to the reader that Ms. Kelley’s borrowing is large but atypical. But he then goes on to note that, “Of the 43.3 million borrowers with outstanding federal student loans, 1.8 percent, or 779,000 people, owe $150,000 or more. And 346,000 owe more than $200,000.” So maybe her experience is not so atypical after all?

What Carey does not tell the reader is that the vast majority of these individuals who borrowed $150,000 or even $200,000 or more to finance their educations are graduates of professional schools, most typically law, medicine, and dentistry. And as U. of Michigan economist Susan Dynarski pointed out in a column earlier this year in the Times, the vast majority of these students are successfully paying back their loans. Only seven percent of all students who borrowed for graduate school ever default on their loans, while 22 percent of those who borrowed only for undergraduate education default.

Borrowing by undergraduates is at much more reasonable levels. Data from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS), a nationally-representative sample survey of college students in the country conducted every four years by the U.S. Department of Education, show that a miniscule proportion of all graduating seniors borrow large amounts. Data from the most recent survey, conducted in the 2011-12 academic year, show that the cumulative undergraduate borrowing of students who were seniors that year was distributed as follows:

Amount borrowed and proportion of seniors:

- No borrowing: 31.0%

- $1 to $10,000: 11.0%

- $10,001 – $20,000: 13.2%

- $20,001 – $30,000: 17.5%

- $30,001 – $50,000: 18.5%

- $50,001 – $75,000: 7.0%

- $75,001 – $100,000: 1.4%

- $100,001 – $150,000: 0.3%

- >$150,001: 0.1%

Even Ms. Kelley admits that she is responsible for the situation in which she finds herself, as Carey writes in the article: “ ‘I am not a victim,’ said Ms. Kelley, who shared her loan documents with me. ‘I made choices.’ ” The fact that she made these choices of her own free will does not mean that we shouldn’t be empathetic to her situation; by all means we should, as she finds herself in this difficult situation at least in part due to factors that were beyond her control (including an illness that struck her while she was enrolled in law school). Because student loans are not dischargeable in bankruptcy, she doesn’t have that as an option to relieve herself of her debt. As Carey notes later in the article, she does have the option of entering the federal government’s loan forgiveness programs, which would cap her payments and forgive a proportion of her debt if she works in the public or nonprofit sectors for ten years.

While factually Carey’s column may be accurate, it reflects a sensationalization of one extreme example as an argument for why public policy – in the form of the federal student loan programs – should be changed.

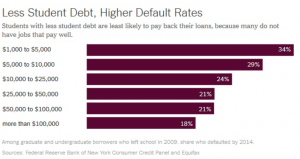

As Dynarski pointed out in her Times column, shown here, the real problem nationwide with student loan borrowing is not generally among large borrowers like Ms. Kelley, but among smaller borrowers. These are most typically students who borrowed to pay for an undergraduate degree, but never completed the program nor attained the benefits of that degree. It is these former students who are the ones who are struggling the most to repay their loans.

Carey would want us to rewrite federal policy based on his anecdotal outlier, but he misses the real story in his column. Better to focus on changing student loan policy to address the problems where they truly reside, rather than focusing on the extreme examples that may make for good copy but are not at all representative of the millions of student loan borrowers across the country.