The Education Week website recently published an article describing allegations of cheating on the Pennsylvania System of School Assessment (PSSA) exams in a number of schools in Philadelphia. Similar to stories from other districts, including Atlanta and Washington, D.C., the allegations state that principals and/or teachers were involved in changing student test sheets after they were handed in, in order to change wrong answers to correct ones. In the case of Atlanta, the allegations have been found to be true, while the Washington and Philadelphia incidents are still under investigation.

The likely purpose behind this form of cheating is to increase the performance of schools, which under the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act passed in 2002 (as the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act) is measured based largely on the performance of students on state curricular framework tests. Under the original NCLB statute, schools had to achieve a standard, known as Adequate Yearly Progress, toward the legislation’s goal of 100% of students achieving proficiency on the state tests by the year 2014. There has been much controversy around the heavy-handed use of student test scores not just for assessing students, but also for measuring school and even teacher performance (the latter of which I wrote about in an early blog post). In response to some of these concerns, the Obama administration has allowed states to apply for a waiver for complying with the requirements of NCLB, as long as they come up with an alternative plan for improving student performance in schools and assessing school performance.

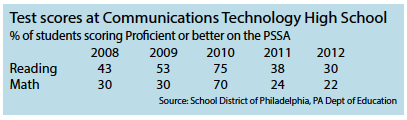

Much of the criticism of NCLB has revolved around its heavy reliance on tests for assessing school quality, and the incentives this reliance places on school personnel to encourage such things as teaching to the test, narrowing the curriculum, or worse, outright cheating on the tests. The Philadelphia case outlined in Education Week describes Saliyah Cruz, a woman who took over as principal at Communications Technology High School in 2010, following a remarkable increase in that school’s performance on the PSSA exams. In one year, the number of students who scored proficient or better on the PSSAs increased from 53 to 75 percent in reading, and from 30 to 70 percent in math. The year that Ms. Cruz took over, however, the school’s results dropped back down again, and continued in the next year:

Jonathan Supovitz, a professor in the Graduate School of Education at the University of Pennsylvania and a co-director of the Consortium for Policy Research in Education there (and a friend and graduate school colleague of mine), uttered a one-word reaction when asked about these results by Education Week: “Wow.” As Supovitz is stating, results like this simply don’t pass the smell test. Unless something extraordinary was going on in that school in that single year, these kinds of swings in test scores are simply not possible in such a short period of time.

When Cruz first came to the high school after the 2010 results, she queried the school staff about what they had done to cause performance to increase so quickly. The Education Week article says that staff in the school gave the credit to a computer-based study skills program as the reason for the large increase. But as a subsequent investigation by the Pennsylvania Department of Education showed, a “a high number of student response sheets at Comm Tech had suspicious patterns of ‘wrong-to-right’ erasures—a telltale sign of adult cheating.”

It is easy to blame NCLB for this cheating, which has received widespread attention around the country. It is important to note that these incidents are by no means widespread; the vast majority of the over 132,000 schools in the country conduct tests with great care, honesty, and integrity. But these isolated incidents where school officials, both administrators and teachers in some cases, do encourage cheating are inexcusable. None of the requirements of NCLB or any other federal or state law should require school employees to engage in unethical, or even illegal, actions. There are legitimate reasons to question the testing provisions of NCLB, but eliminating them because they provide too many incentives for cheating is not one of them.