I was on vacation back east last week, not far from the small town in Connecticut in which I grew up. I lived there from birth until I graduated from high school and went off to college. Madison was small, at least by the standards of the eight other places I have lived since then, all of which dwarf Madison in size. The population when I left in 1977 was somewhere in the ballpark of 10,000 people; the most recent census data show that the town has grown somewhat since then, but as of last year the population was still only about 18,000.

There were not a lot of diversions for an adolescent the town back then. There was no arcade; in fact, I don’t think there was even any public place that had a pinball machine. There was no fast food; the closest was the soda counter at Jolly’s, one of two drug stores in the town. Television was limited to over-the-air channels, which consisted of the three major networks, ABC, NBC, and CBS; public broadcasting; and three independent stations from New York City – WOR, WNEW, and WPIX – which I recall broadcast mostly reruns and professional sports.

So I spent a lot of my childhood playing outdoors with friends, through all four seasons, everything from sports – baseball in the spring, football in the fall, basketball year-round – to games like kick the can, spud, and tag. When the weather was bad, we were indoors playing games such as Monopoly, Parcheesi, and card games.

While I enjoyed playing with friends, I also at times enjoyed the solitude of being on my own. I have memories of spending hours in my room with construction sets of various kinds – Lincoln Logs, Erector Set, wooden blocks, and something whose name I don’t recall that allowed one to build elevated roadways for Matchbox cars.

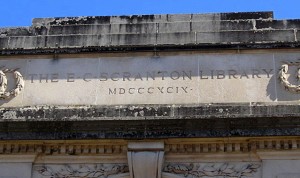

But one thing our small town had was Scranton Memorial Library. In my tween and early teen years, I spent many afternoons after school, or on weekend days, riding my bicycle from home to the library. With the assistance of Google Maps, I can today determine that the library was precisely 2.2 miles from my home. The ride required me to ride in part on a major road, Rt. 79, which had a lot of fast-moving traffic, but which had fairly large breakdown lanes that were wide enough to allow one to ride a bicycle with little fear of getting clipped by the rapidly-moving traffic. The route took me about 15-20 minutes to traverse on a typical day.

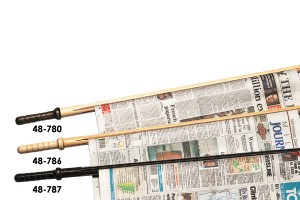

I recall spending hours in that library. Right off the entrance was a comfortable reading room containing current issues of numerous magazines as well as local and some national newspapers. The newspapers were bound into long, wooden poles, held together with strong rubber bands; I remember that you had to take the newspaper out of the pole in order to read anything within a couple of inches or so of the left or right edge.

There were news magazines, such as Life, Look, and Time. I was very much into photography as an adolescent, had my own darkroom, and worked as a free-lance photographer for the local weekly newspaper, so Life was my favorite, largely because of the ubiquitous and beautiful photography. I read Popular Mechanics, Popular Science, as well as a host of photography magazines.

I read books as well. In addition to periodicals, the reading room also contained a shelf with newly-acquired books, and on most of my visits I would peruse the titles to see if anything looked interesting. While I do not recall the titles of most of the books I read, I do have memories of a few that stand out. I recall reading the Knapp Commission Report on Police Corruption, which described the rampant corruption in the New York City Police Department in the 1960s and 1970s, and was later highlighted in the Al Pacino movie, “Serpico.” I do not remember why I chose this volume, but I have a strong memory of reading it one day when a friend of my parents who was a former detective in the NYPD came by the house. He was outraged to see the volume in my hands, as the report was highly critical of the department and many of the people who worked there.

I also recall reading many books about architecture, as in my early teen years I had thought about that as a potential career (an aspiration that was never realized). And my interest in photography also drew me to many books on that subject, both how-to volumes to help improve my craft as well as studies of the work of the prominent photographers of that and earlier eras, such as Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, and Alfred Stieglitz.

But the books I most vividly recall reading were the crime novels of Donald E. Westlake. I do not remember with any degree of certainty how I first discovered them, but it was fairly early on after I was old enough to begin making my own bicycle-powered forays to the library. I do not think anybody recommended them to me; I likely just stumbled across them perusing the fiction shelves of the library, or there may have been one of his books on the new releases table in the reading room. It could have been a humorous title that caught my eye at first, or perhaps it was the cellophane-clad paper cover with a photograph or drawing that stood out that grabbed my attention, or maybe it was just that we shared the same first name and middle initial.

Westlake’s work was in a genre I would describe as comedy crime novels. They were deftly-crafted, funny books that made light of many of the characters in them. The victims, the criminals, the police who investigated them – all were fair game for Westlake’s skewering.

I do not know how popular his work was at the time, as I do not remember how well the book’s check-out cards (which listed the names and dates of all those who had checked out each book) were completed before I got to each one.

To this day, I do not know what it was about his writing that grabbed me and reeled me in. Whatever it was, I read in succession every single volume of his that the library owned. After going through all of them, a year or so later I would return and reread them. This may strike one as strange, since I clearly remembered the denouement of each, which you would think would make reading it again a less-than-satisfying experience. But I kept returning, often multiple times, to some of my favorites.

While I had always enjoyed reading, it was Westlake who I give credit to for turning me into a voracious reader, one who would devour both fiction and non-fiction. After discovering his work, whatever book or books I took home were consumed fairly quickly; it was rare for me to have to bring one back to the library to be renewed for an additional two-week term. I could hole myself up in my room and read for hours on end, sometimes to the now-admitted neglect of school work. I enjoyed reading not just for the knowledge I gained, but for the pure joy and satisfaction of the experience itself.

In part 2, which will be posted tomorrow, I describe how reading has changed for me since my childhood and my concerns about today’s generation of readers.