Sonja Martin Poole’s research explores gamification and influencing behavior. During our conversation, we discussed her path to becoming a professor and how she navigates interdisciplinary research.

When you started at the University of California Berkeley, were you focused on becoming an academic or did you consider going into business?

Even though I come from a long line of educators, I wasn’t focused on becoming an academic. My grandfather was a geography professor for many many years at Southern University in New Orleans, which is where I’m from, and my grandmother was an elementary school teacher. My mother is an elementary school teacher. I have an uncle and two aunts who are university professors. I wanted to do something different than everyone else in my family, so I initially went to college with the intent to be a lawyer. In the middle of freshman year, I decided that I wanted to go into business. However, I took microeconomics, one of the prerequisites of the business major, and said, “This is it. This is a new way of thinking. I love this.” I got a bachelor’s in economics and then later a master’s in public sector economics. I had no idea at the time what I would do with my economics training. I was just intrigued by it.

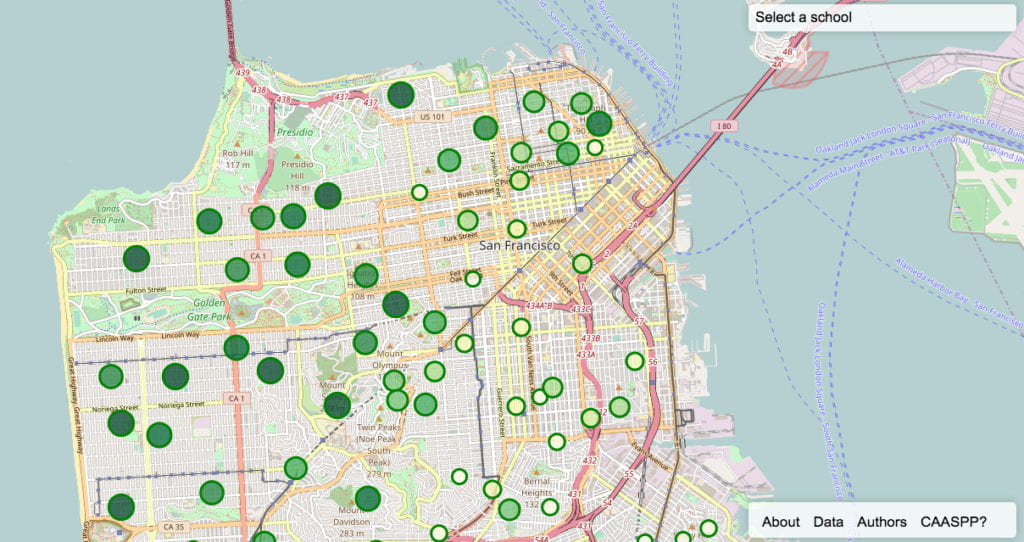

While I was in graduate school, I worked as a high school teacher in a public school. It was then that I started asking economic questions about educational institutions. I became interested in studying the ways in which education resources are distributed in our society and if there’s a way that we can develop educational systems that are more efficient. That’s what I studied in my Ph.D. program.

Somewhere along the way I then became intrigued by the ways that educational institutions strategically attracted students, maintained a student body, and communicated value. That’s a marketing question, so after my Ph.D., I did a post-doc in marketing.

Was it the experience in the classroom that made you want to change the world?

I really wanted to improve people’s lives, and I saw how educational systems can influence people’s beliefs, behaviors, and life trajectories. In graduate school, I wanted to study how we can improve these structures.

What work are you most proud of?

Right now, I’m looking at the ways in which games can influence people’s behavior. I first became interested in this topic when tracking devices for fitness came out like Fitbit. This device had a gamified aspect. Within the application, users can compete not only against themselves and their own progress but against others that you may or may not know. It presents an incentive to do more. I found myself drawn to this device and to the activity that the device personally encouraged me to participate in.

I then began to wonder if gamification can be used to influence other behaviors, ones that have a big impact on our environments and communities. Can we use it for getting people to recycle more, drive safer, or donate to charitable causes? What about using the tool to reduce or eliminate social problems such as racism, poverty, or disease? Can we get people to do things that they otherwise wouldn’t do just by making it fun? I am interested in the practice of influencing people to do things that are not only good for them, but also for society as a whole.

How does your research come into the classroom?

My students are the best people to run my ideas by because they’re honest, and they’ll give me hypotheses to test in my research. For that reason, I love dealing with students regularly because they bring fresher ideas to light.

A few years ago I developed a course called Marketing for Social Change. In this course we examine marketing strategies that can influence individual and collective behavior for social good, and while teaching this course, I identified my interest in gamification. Gamification was introduced as a possible means to encourage pro-social behavior and I got a sense from my students that it is worthy of further study.

Your work sounds very interdisciplinary. How do you navigate the different disciplines or how do you try to work between them or with them?

Economics is the basis of all that I do. It’s all about incentives, incentivizing behavior, and that is my foundation. When I was in my Ph.D. program, I got into educational policy with the idea that I was going to apply economics and economic decision-making tools to education policymaking. As a marketing professor, I now use behavioral economics to understand and explain consumer behavior. Marketing and education are both disciplines that are based on some other foundational discipline, such as psychology, sociology, or economics. We use the foundational disciplines to inform what we do in marketing and education. I tend to think like an economist.

How has being at USF impacted your research?

USF has been supportive of the kinds of things that I want to do. Every activity that I’ve been involved in has been not only encouraged but also supported through resources and collaborations and people wanting to help. I feel that spirit of helpfulness throughout everything that I’ve done here and almost every interaction at USF, and that includes writing retreats that are supported by the school to make sure that researchers get research completed and writing done.

USF also provides opportunities, such as the Ignatian Faculty Forum, to consider our role as professors, Ignatian values and mission, and how those things relate. The development opportunities help to shape my ideas around what I want to do in the classroom and in my research. In addition to that, I participate in different faith formation activities here at USF. They are particularly valuable for thinking people. I appreciate the opportunity to participate in those kinds of opportunities whether they be the Spiritual Exercises or silent retreats, or any other University Ministry activities. That’s really the unique aspect of being here at this University—finding out how your spirituality and your sense of self relate to your work. It’s very hard to separate that out—who you are spiritually and your vocation are intimately connected, or at least I believe they should be. I really appreciate those opportunities to think through and talk to other people about these ideas.

What brought you to USF?

I believe that the university mission is in line with my own personal mission. I came to USF because I wanted to be an agent of change. As long as the university continues to be about social justice and life-changing action, I will love being here.