Sadia Saeed is a historical sociologist who researches global inequalities. During our conversation, we discussed how growing up in Pakistan shaped her and how she brings her research into the classroom. Her book Politics of Desecularization: Law and the Minority Question in Pakistan is now available.

Thinking about your start, when did you become interested in global inequality?

I hail from Pakistan, which is where I first studied sociology and history as an undergrad. Many of these courses were quite explicitly organized around questions of global inequalities, and these questions have stayed with me since. Oftentimes when we talk about issues around nationalism or rights, it’s not put in the context of global inequalities. I think this is a serious omission because a lot of what is going on in the world today in supposedly domestic contexts can be explained, or at least further clarified, by taking the global dimension into account.

How does your research in sociology look at aspects of global inequality?

In my first book, I examined how inequalities are produced in a local national context by looking at the issue of religious minorities and their rights in Pakistan. As I concluded that project, I became interested in how domestic inequalities are justified, or at least tolerated, within systems of international law, how rights are articulated in international law, and how global inequalities shape how different people think about international law. Basically, I’m now trying to connect what happens domestically to global structures and vice versa.

What was the moment that first sparked your interest in really understanding global inequality?

When you come from the so-called developing world and study social sciences, you can never really escape the profound gaps that exist between the West and the rest of the world. Also, growing up in a place like Pakistan, you just know that there are global inequalities and that these are not natural, and it was household talk that IMF and World Bank and other such global institutions are run by Western countries. I remember many conversations around how the IMF was imposing things on Pakistan —collecting more taxes, cutting state expenditures—and the American military involvements in the region and their continuing effects also clearly pointed to other kinds of global inequalities.

What brought you to the United States to complete your Ph.D.?

America has some of the best universities in the world and some of the most dynamic researchers and scholars. It’s so diverse, and you can learn more here because there are better resources and better training.

What is your research process like when you’re exploring these topics?

For my first book, which just came out, my research process was very field-based. I spent a lot of time in Pakistan. It was very organic. I was interested in why and how the Pakistani state instituted laws which favor the dominant religious group of Sunni Muslims over others and why the states discriminates against particular minorities. How and why does the state make these decisions, especially when they run counter to values of equality that the state also claims to uphold?

I looked at newspapers to figure out the events that were happening at the time when people were making these decisions. I went and spoke to a lot of activists, government officials, and people who were part of the deliberations in making these policies. That was really eye opening because you understand the constraints with which state officials work.

Pakistan often makes policies against religious minorities because that is what the majority wants, or at least that is the justification the state gives. Oftentimes, proponents of discriminatory laws say that such laws are actually democratic because they are what the majority desires— they say that the will of the majority should be heard.

We tend to think that discrimination in places like Pakistan against religious minorities is a different beast than what you might see here in the United States, with respect to race, for example. But in Pakistan, as with everywhere else, there are also activists such as the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan and a lot of dedicated lawyers and judges who push back against these policies. People write against policies in venues they think are safe. They talk against these laws when they think it is safe.

I could not have learned a lot of what I subsequently wrote about without doing a lot of research. In my book, I focused on both the people who made discriminatory laws and the people who pushed back, the constraints that both sides faced, and the constraints continued to be faced by activists and people trying to change these laws.

Tell us about your new project.

My second project is in the initial stages and looks at how minority rights are instituted in international organizations, particularly in the United Nations and the United Nations predecessor, which was the League of Nations. I’m looking at international laws surrounding minority rights—which countries and which groups of people or individuals have pushed for specific declarations, conventions, etc. I’m also interested in questions of resistance to international law, especially forms of resistance that are premised on arguments about global inequalities. I am also interested in looking at international laws against racial discrimination, those advocating for indigenous rights, and also the convention against genocide.

This is a tentative thought, but it also seems to me that not all minorities are treated equally when it comes to matters of international law. Some minorities figure more when it comes to drafting international laws and others are marginalized in the discourses surrounding minority rights. Some marginalized groups are invisible and others become very visible. Some genocides become internationally recognized whereas other genocides do not. Not all minorities and not all groups’ narratives and plights are equally important in international law, and this goes back to questions of domestic and global inequalities. Who makes these laws? Who are they supposed to protect? Which minorities get left out? What is the politics behind it all?

How does your research inform your teaching?

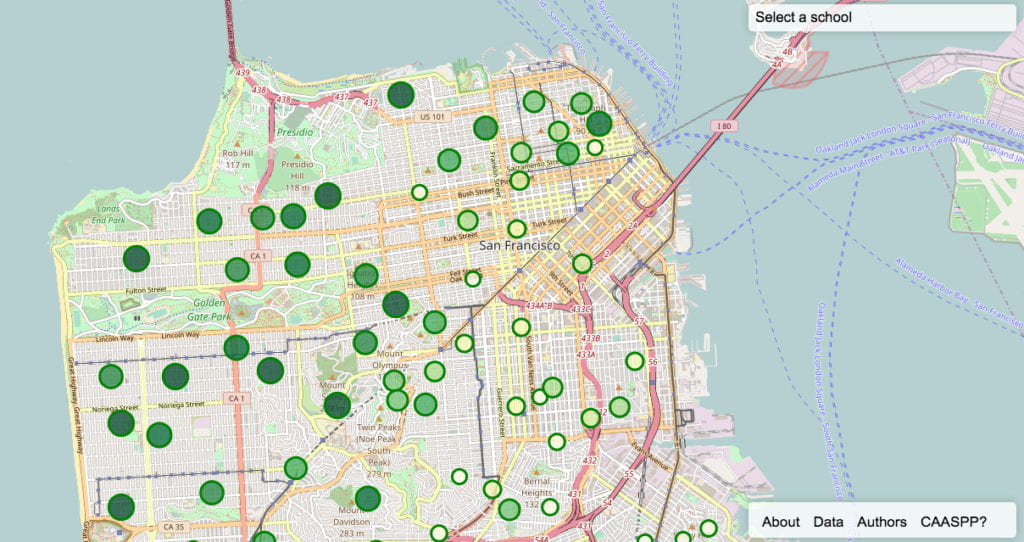

When I teach, I try to convey to students critical approaches to questions of global and domestic inequalities. I try to get students to understand the social issues that people in the rest of the world, that is, outside U.S. face. There is an idea that something happening in Pakistan can’t possibly help us think about what is happening here in the United States. It’s hard in this globalized world, but a world that also creates highly segmented and stratified communities, to really understand how things are connected. I try to bring in everything I work on and what’s dear to me in my research and translate that into my teaching. Students everywhere long to learn new things and they want to question and to be pushed, but often it means that you have to do it in creative ways. For me, this creative way is through literally thinking outside the box, that is, thinking beyond the U.S.

Are there specific moments when you see your students come to an understanding?

The first semester here I taught a course called Islam, Politics and Society, and when we began, people had very different perceptions of the relationship between Islam and politics. Some people were suspicious of religion and politics. Some people were more sympathetic to the idea that different cultures do things differently.

Over the course of this amazing semester, everybody still had different opinions but everyone was able to talk to each other and discuss the pros and cons of one position and the pros and cons of another position. I think everyone left the class knowing a little bit more about the issues that are at stake. I could see the students learning because I could see them talking to each other and really engage with other ways of thinking. This was just a fantastic course for me.

What brought you to USF?

The University of San Francisco was one of the really exciting places for me to interview at because the job ad was for global inequality, which is precisely what I work on. Also, USF has such a wonderful mission of social justice, and my work fits in really well with this university. And I loved my campus visit. I am still quite new here. This is my first year here.