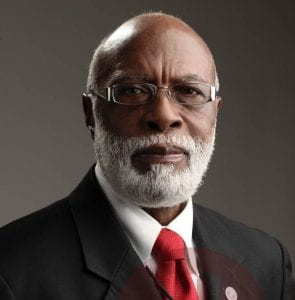

Rev. Arelious Walker, born in the small town of Atlanta, Texas, in 1931, was deeply influenced by the wisdom of his grandfather, Cleveland Walker, a sharecropper who later saved his money to acquire 9.5 acres of land in Texas. As a child, Walker experienced first-hand the difficulties—and the importance—of education, and its importance has been a lifelong priority. When he came of age, Walker joined the military; he was stationed in West Germany in the 1950s as part of an all Black company. Upon his honorable discharge, he came to San Francisco and trained to be a barber. Walker soon joined the ministry and the soon-to-be legendary community pastor opened his True Hope Church of God in Christ in the Bayview District on May 12, 1968, with the help of his wife, Hazel Walker. And although Walker has always demonstrated an immense ability to help others and be proactive in aiding impoverished communities, his church is the defining keystone of his career. It started with only a few members, but after years of hard work and expansion, they were able to move to a larger location in the Bayview on Gilman Avenue in 1978.

As Arelious focused on expanding the influence of his church, he ensured this by directly impacting the lives of many in his community. He was especially influential in offering the church as an alternative to drugs and crime in the Bayview, having gathered hundreds of people for talks of drug rehabilitation, strongly announcing that “when you accept Christ, you have no withdrawal.” Around this time, he created thousands of pamphlets entitled “What’s Happening in Our Black Neighborhoods” that served as motivational literature for those seeking a new opportunity in life away from drugs and crime. He also frequently visited housing projects, street corners, and broadcast his talks over the radio. His broadcasts featured his work at San Bruno Jail, where he would visit inmates and conduct regular worship services.

Homelessness was another issue that True Hope tackled. As Walker put it: “We’re a community-oriented church.” He wanted to help, but also wanted to make help far more available. Helping people with housing became a constant priority. By 1983, he helped organize more than 700 landlords and tenants from across San Francisco to meet at City Hall, attempting to bolster the city’s rent control laws. In 1987, he also helped garner 32,078 signatures to propose a measure that would elect San Francisco supervisors by district. “This is a mandate from the people of San Francisco… District elections will hold the supervisors of San Francisco accountable to the people.” These are prime examples of the community activism that made Arelious such a special leader and a revered pastor.

In 1994, Walker held an Open Forum about the problem of incarceration with fellow changemaker Rev. Dr. Amos Brown. He led one of the most effective jail ministries in the nation, uplifting the lives of countless citizens. His Caring and Restoration Home helped ex-offenders transition from prison back into the world. He was quick to give attention to the vast difference in incarceration rates between neighborhoods like Pacific Heights and the Tenderloin or Bayview.

He put this same reforming effort toward job growth, such as in the Home Depot debate of 2002. Certain community officials argued the store’s introduction in his neighborhood would diminish local business, but Walker saw it as an opportunity for more than 200 jobs to surge into the community: “This isn’t just about the jobs,” he said. “This is about a neighborhood’s right of self-determination. It’s about respect.” That same year, after his congregation had grown significantly, the church was able to expand by 30,000 square feet.

The True Hope Church was chosen as the site for the new Bayview Hope Housing Project in 2003, as Walker’s leadership for more than 35 years promoting spiritual solace, daycare, substance abuse rehabilitation, and job skills training did not go unnoticed. Mayor Willie Brown, along with a handful of others, worked alongside Walker in creating this groundbreaking low-income housing complex on the parking lot of True Hope. Any extra revenue the church garnered, Walker said, would go toward paying off the church’s mortgage, funding a new computer learning center, and a neighborhood association to keep the area clean.

The Tabernacle Community Development Corporation was created to address housing needs, and it has grown tremendously under Walker’s leadership: TCDC oversees properties at 3300 Mission Street, the Mary Helen Rogers Senior Community, the Alice Griffith Apartments, the Tabernacle Vista Apartments, the Westside Courts, and the Robert B. Pitts apartment homes. At the age of 94, he is still working alongside his granddaughter Lenika Howard in supporting the TCDC.

Rev. Walker was recently recognized by having a street named in his honor. His immeasurable commitment to community activism for more than 50 years has cemented Walker’s legacy as a changemaker.

— Marcelo Swofford and Zachary James

Works Cited

Ford, Dave. “Helping Home Buyers Get a Foot in the Door.” SF Chronicle. 9 May 2003.

True Hope Church of God in Christ. 2019.

Howard, Lenika, and Rev. Aurelious Walker. Personal interview.

Hsu, Evelyn. “Packed Hearing on Rent Control.” SF Chronicle. 27 Oct 1983.

Lomax, Almena. “True Hope Pastor Who Reforms Wrongdoers.” SF Examiner. 23 Mar 1974.

Pereira, Joseph. “‘Voice for the Voiceless’ in SF.” SF Chronicle. 16 May 1983.

Pogash, Carol. “Once Often in Jail, Now Often in Church.” SF Examiner. 10 Aug 1973.

Roberts, Jerry and J.H. Doyle. “SF District Election Petitions Turned In.” SF Chronicle. 23 Jul 1987.

“The Black Church Should Get its Due.” SF Chronicle. 9 Feb 1994.

Garofoli, Joe. “Neighborhoods Divided over Home Depot Plan.” SF Chronicle. 29 Apr 2002.

Wood, Jim. “It’s True Hope: SF Church Makes Plans to Help the Homeless.” SF Chronicle. 19 Dec 1982.