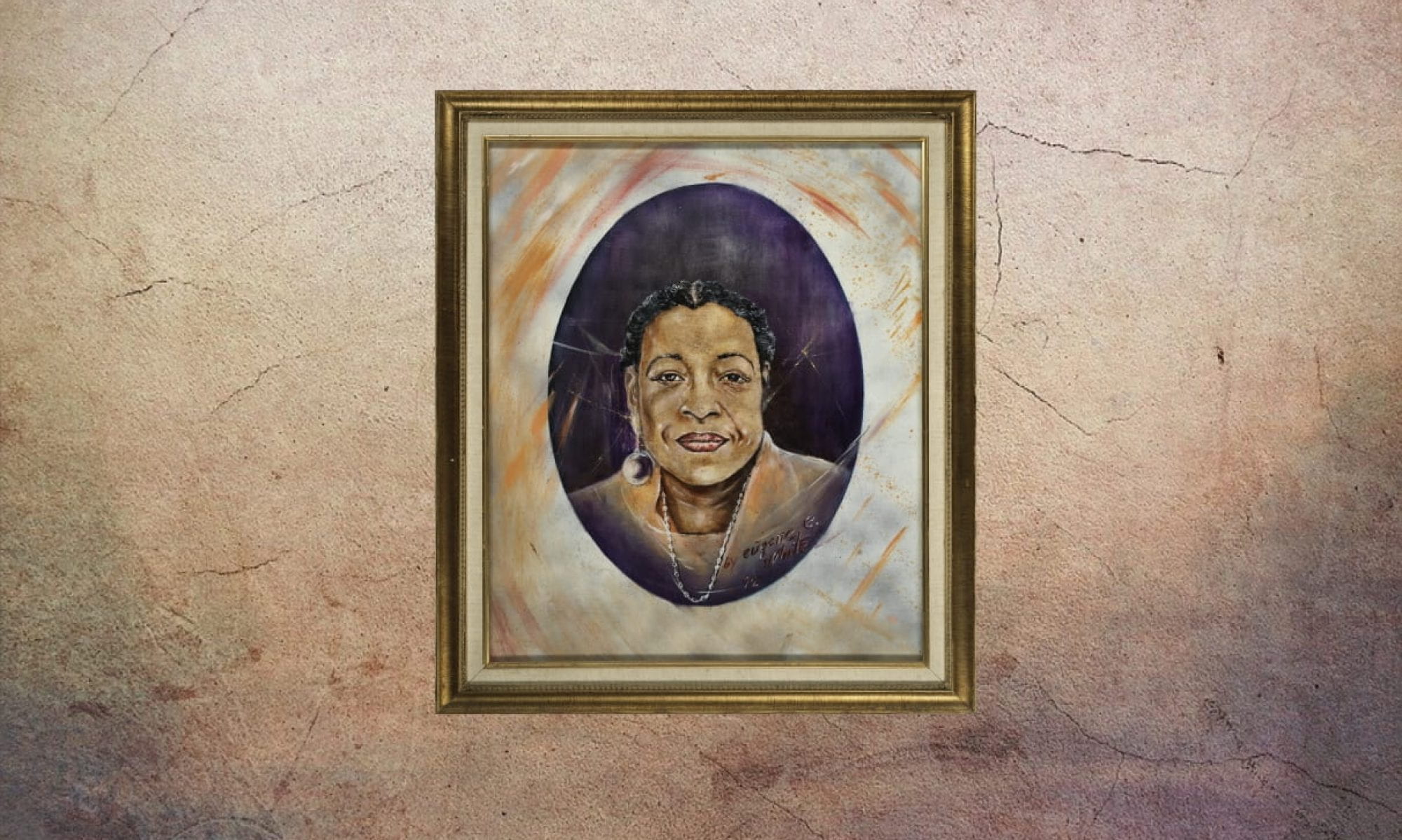

“Orville Luster had a presence—that he was everybody’s father whether you were black, brown, blue, red or yellow,” said Percy Pinkney, a former Youth for Service intern (Bulwa). Orville B. Luster, stood 6′ 2″ tall, and was nearly always seen with a cigar between his lips. He stood at the forefront of advocacy for reforming gang members in San Francisco’s Hunters Point, Tenderloin, and Mission neighborhoods, as well as the Western Addition (Stevens). He dedicated his life to fighting the cycle of gentrification and violence that plagued these neighborhoods. Having been a San Francisco social worker and human rights commissioner, he worked hard to encourage gang members to return to school, often filling their days with community work ranging from painting and rebuilding homes to restoring playgrounds (Bulwa).

Born in Oklahoma City on May 20, 1925, Luster was the second of seven children. After graduating as the president of his senior class at Frederick Douglass High School, he served in the army in both Asia and Europe during World War II and was later discharged as a Master Sergeant (Bulwa). After serving, Luster moved to San Francisco in 1946, attending San Francisco State College. Upon graduating, he cleaned oil tankers in the San Francisco shipyards while also working in auto sales and as a Safeway clerk. In 1956, he served as the first African American counselor and supervisor at San Francisco’s Log Cabin Ranch, a juvenile rehabilitation center (Bulwa). There began Luster’s true calling: social work and youth services. This led to him joining Youth for Service in 1959, a local project, that he would eventually preside as executive director (Bulwa). Throughout the fifteen years he served as executive director, Luster worked hard to support the kids who were caught up in the neighborhood gangs.

One of the greatest accomplishments of his career was working with James Baldwin, famed author and activist, to create a KQED film that toured the impoverished African American neighborhoods of San Francisco, focusing on the Western Addition. The intent of this film was to discover “the real situation of Negroes in the city, as opposed to the image that San Francisco would like to present” (“Take This Hammer”). He was very proud of his efforts towards getting the youth engaged in the community, with projects such as the Double Y Project which was added to the YWCA property (“15 Juveniles”).

One of Luster’s main personal goals was to supply youth with sustainable jobs. With this in mind, he managed to receive a grant of $483,400 in July 1966 for Youth for Service, igniting enthusiasm from the wider community, as this money went towards providing local youths with jobs (“Another Grant”). He also received a $16,000 grant from the Ford Foundation to redirect gang activities from their usual “hangouts” towards a path of education (Stevens). He stressed the need for permanent jobs rather than seasonal ones (Draper). In the same article, his Youth for Service team was lauded as “probably the most effective and unique staff of . . . social workers in the nation” (Draper).

Luster emphasized the importance of teaching teenagers how to act around authority, softening the tension in their interactions, often by using what he called the ABCs (Always Be Cool) to urge the youth to be polite and respectful when questioned (Schneider). He hoped to provoke a change of attitude towards police, as Luster “believed that every young person had some goodness in them, and he worked to spark that” (Bulwa).

He was the fifth person to win the Liberty Bell Award, receiving it on May 2, 1968, from the Bar Association of San Francisco, with its President, Richard C. Dinkelspiel, speaking highly of Orville, saying that “Luster’s life and work best exemplifies the desire to strengthen and safeguard the blessings of liberty as conceived and protected by our form of government” (“Lawyers Honor”). By 1973, Luster left Youth for Service to pursue independent counseling, only to later return in the 1990s.

He has been acknowledged by very prominent associations in San Francisco and received many accolades for his service. Orville Luster was committed to pushing people toward completing their education, doing anything possible to help them achieve this. Of the hundreds of youth who came through Youth for Service in the 1960s and early 1970s, many of them became doctors, lawyers, teachers and business leaders.

Luster died of a heart attack at Kaiser Permanente San Francisco on June 27, 2005 (Bulwa). Changing and potentially saving the lives of hundreds of youth in the Bay Area, Luster epitomizes selflessness and the change that one person can elicit among many.

— Marcelo Swofford and Kendra Bean

Works Cited

“Another Grant For SF Youth.” SF Chronicle. 14 Jul 1966.

Bulwa, Demian. “Orville B. Luster—Social Worker, Friend to S.F.’s Youth.” SFGate. 7 Jul 2005.

Draper, George. “Luster Calls For 10,000 Youth Jobs.” SF Chronicle. 1 May 1969.

Larry Schneider. “Talking To A Cop? Be Nice.” SF Examiner. 31 Jul 1961.

“Lawyers Honor Youth Leader Here.” SF Examiner. 2 May 1968.

Stevens, Will. “Gang Returns Girl to Officers.” SF Chronicle. 3 Dec 1960.

“Take this Hammer: Classic 1963 Film of James Baldwin Touring the Hoods of San Francisco.” San Francisco Bay View.

“15 Juveniles at a Vacant Lot—Bricks Fly, but the Cops Smile.” SF Chronicle. 12 Nov 1963.