shocking deaths at Jonestown. Image courtesy of Mike Kepka/SF Chronicle/Polaris.

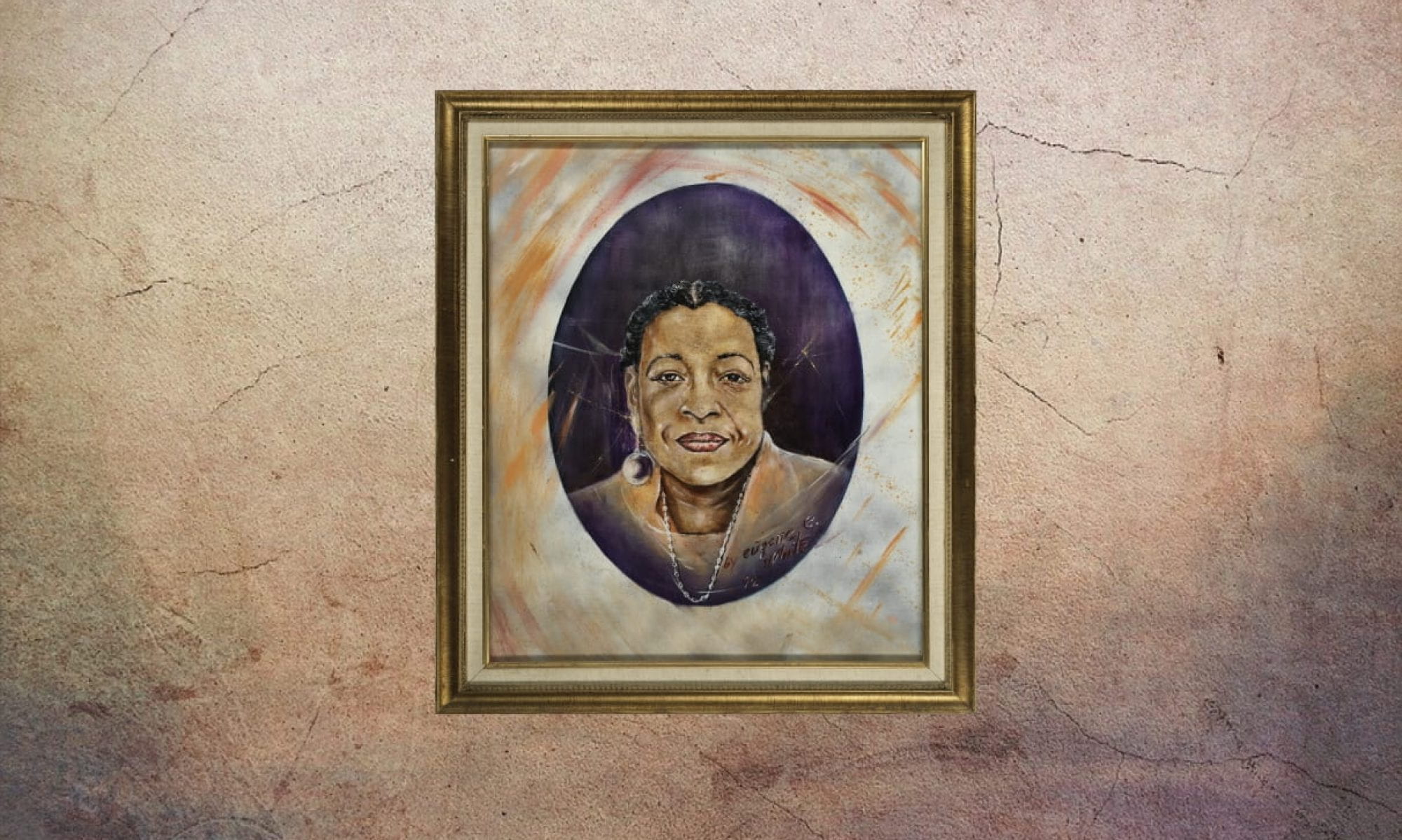

Donneter Lane, wife of Rev. John Lane of Grace Baptist Church in Hunters Point, started her activism by interweaving her own spirituality and her hopes for an educational desegregation for San Francisco students (“Church Council”). In the 1960s, Donneter Lane helped create a desegregation plan for the San Francisco Unified School District, which allowed black students access to all schools. Her focus on school desegregation transcended into working with communities in San Francisco that were adversely affected by the War on Drugs that had just begun in places like Bayview–Hunters Point and the Western Addition. Lane, along with other famous changemakers, believed in the power of a unified community, engaged youth, and an intersectional perspective.

Throughout the 1970s, Lane focused on the uplifting of disadvantaged communities in order to foster youth engagement. She became the associate director of the Oceanside Merced Ingleside Community Educational Planning Program and led community workshops focusing on engaging minority teenagers within the home about education, success, and career opportunities. In addition, the Lanes also hosted workshops for black mothers in working with their sons and daughters on issues of public safety, black culture, and equal education (“Self-Examination Urged on Mothers”). Her initial goal of desegregating San Francisco’s public schools finally came to fruition in 1972, when she was invited to become a part of the San Francisco Unified School District’s Emergency School Assistance Program Multi-Racial Advisory Committee, focusing on youth engagement, educational opportunities for youth of color, and, of course, desegregating public schools (“San Francisco Unified School District”). The Emergency Task Force was, in part, due to the recalcitrant resistance of urban centers to adapt to reform efforts spurred by Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and 1955. In combination with her community activism, Lane also served as the President of San Francisco Council of Churches for two consecutive terms, inspiring change within San Francisco congregations, which ultimately spurred successful partnership between disadvantaged communities in San Francisco later, thanks to her championing of social justice (“Church Council”).

Donneter Lane served as the head of the African American Historical and Cultural Society

In 1979, as Executive Director of the San Francisco Council of Churches, she acted as one of the principal organizers of the Guyana Emergency Relief Committee, formed on November 28, 1978, to coordinate an interfaith response to the shocking deaths at Jonestown, which sadly included many members of the Western Addition.

By 1986, Donneter Lane had formed the Bayview–Hunters Point Crime Abatement Committee, modeled after a similar community task force in Oakland. The point of the task force was to advocate for the Bayview–Hunters Point community to rally for crime prevention. Their biggest protest occurred on December 7, 1986, in which 1,000 residents of Bayview chanted “We Shall Overcome” as a result of community aggravation over the drug dealing and public safety crisis that was occurring in their neighborhood. During the rally Donneter Lane famously said, “People from those areas are here today to help us and we’ll do everything we can to help them. It’s everyone’s problem” (O’Connor). This obviously caught the attention of former Mayor Art Agnos, who in 1988 appointed Donneter Lane to be one of seventeen members of a city-wide task force concerning the scheduled demolition of public sites in relation to redevelopment and urban planning (“Agnos Names”). Lane understood that achieving educational equity in San Francisco also meant tackling issues like public safety and public housing.

After her long history of advocating for the black minority in San Francisco, Donneter became the head of the African American Historical and Cultural Society, located in the Western Addition. The society focuses on the preservation and cultivation of African American history and culture. Even now, it stands as a purposeful landmark of resilient culture and strength in the Western Addition. In 2001, Donneter retired from her social justice advocacy in San Francisco and moved back to Arizona to spend her last years with her family (Chen). Throughout her career as a voice to the voiceless her belief that “blacks didn’t just come in here. They’ve been here . . . and they’ve made significant contributions to the city” is a true expression of her incredible devotion and community activism in San Francisco.

— Sophia Tarantino

Works Cited

“Agnos Names 17 to Demolition Panel.” SF Chronicle. 24 Feb 1988, p. 2.

Chen, Ingfei. “Black Tourism Plan for S.F.” SF Chronicle. 30 Sep 1992, p. 15.

“Church Council Leader.” SF Chronicle. 25 Jan 1977, p. 14.

O’Connor, John D. “War on Drugs Draws 1,000 to Bayview March.” SF Examiner. 7 Dec 1986, p. 41.

“San Francisco Unified School District.” SF Chronicle. 10 Feb 1972, p. 34.

“Self-Examination Urged on Mothers.” SF Examiner. 3 May 1970, p. 7.