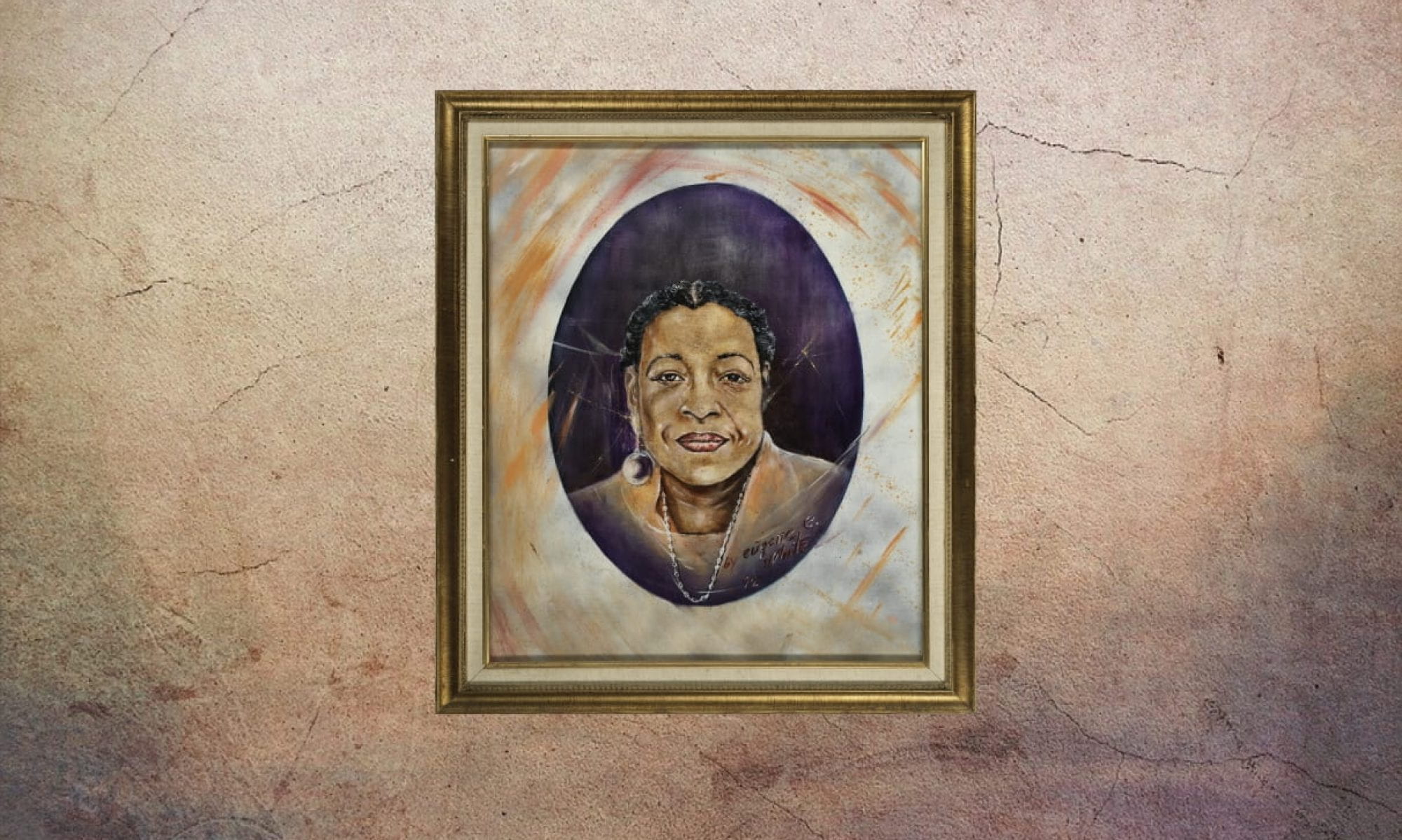

Enola D. Maxwell was born on August 30, 1919, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to Clemus and Lena Maxwell. After her mother’s move to San Francisco, Maxwell followed in 1949 with her children, Barbara and Ronnie. Racial discrimination shrouding the atmosphere of the south motivated her to move to the west. However, she noticed segregation was still prevalent in San Francisco, just more subtle.

Because of her race, Maxwell was prevented from becoming an insurance agent, a job she held in Baton Rouge. Due to financial hardships, they moved around the city in pursuit of affordable housing. The family lived in the Haight–Ashbury District briefly, then moved to the Carolina Projects in Potrero Hill where her third child, Sophie, was born. Maxwell worked with her mother at the Little Red Door, a popular community thrift shop, in addition to working multiple other jobs. She also worked as an employee for the U.S. Postal Service to provide financial stability for her family. Maxwell hadn’t initially expected a life in social activism, yet her involvement in the communities of San Francisco increased her engagement. Her assertive personality was perfectly suited for activism. She enjoyed her first experience serving in the Haight–Ashbury Neighborhood Council in the 1950s. Maxwell, along with close friend Ruth Passen, helped stop a motion to build a freeway through Golden Gate Park. This proposed action would have changed not just Golden Gate Park, but the entire city. The two friends would continue to aid discriminated African Americans, fighting the “worst kinds of white supremacists” (Moan). From 1968 to 1971, Maxwell was the first woman and first African American to work as a minister at the Potrero Hill Olivet Presbyterian Church. She connected the church with the community as much as possible, developing a program titled Street Ministries where she would run a coffee shop in the basement of the church. Music and provocative discussion could be had at the coffee shop without the fear of judgment.

Maxwell established herself as an esteemed community activist in San Francisco and was appointed as the Executive Director of the Potrero Hill Neighborhood House (PHNH). In 1971, she not only became the first black director, but also the first African American to be appointed to any position in the PHNH. In 1977 under her leadership, the PHNH was designated as California Historical Landmark No. 86. One of her priorities in office was to hire Ruth Passen as secretary of the community center. Passen had much to say about the way Maxwell revolutionized the structure of the PHNH. “Enola was the one who had the vision to make it happen,” Passen said. “Her vision was all living together. This is a house. She encouraged black seniors to come. White seniors were already having lunch. This is not a white program or a black program. This is a lunch program. . . . Now we have this place people are not afraid to come to day or night . . . because it’s known as a safe place” (Weiss). Though justice and equality were her vocation at the community center, politics identified her lifestyle as a whole.

Aside from her work at PHNH, Maxwell was extremely involved in everyday politics, not only just in Potrero Hill, but in all of San Francisco. She was often the sole black woman working for programs that were mainly white. Collective justice was her goal at the PHNH and she once asserted that “fear and hate are the most dangerous things because they take away your freedom” (Pelosi). She was one of the founding members of the Martin Luther King, Jr., Holiday Celebration Committee, which still runs events that extend King’s legacy and promote social and political activism citywide.

Maxwell’s passionate activism has led to a lifetime full of achievements. She received a Congressional Award in 2003 from Congressman Phillip Burton. Nancy Pelosi also appointed her to the Senior Internship Program in Washington, D.C., that is run through the San Francisco city government. In 2001, San Francisco Board of Education Commissioner Mark Sanchez officially renamed the Potrero Hill Middle School to be the Enola D. Maxwell Middle School for the Arts. She had often worked with school executives and teachers to advance local education outreach. Though the school has now been discontinued, the 655 De Haro Street San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) facility is now named after her. Longtime Mayor Willie Brown, who she had worked with during her time at the PHNH, has called her “a giant in the community, the quintessential neighborhood activist” (Hoge).

Enola D. Maxwell passed away at the age of 83 on June 24, 2003, in San Francisco. She lived a long life working hard to establish a sphere of freedom and justice in which people of the city could live peacefully, regardless of race, ethnicity, or age.

— Marcelo Swofford

Works Cited

Hoge, Patrick. “Enola Maxwell—Activist, Advocate.” SF Chronicle. 25 Jun 2003.

Moan, Rebekah. “Potrero Hill Populated by Powerful Women.” The Potrero View. Jul 2015.

Pelosi, Nancy. United States, Congress. 5 Jul 2003.

Weiss, Mike. “Civil Wrongs Inspire Activist’s Fight for Rights.” SF Chronicle. 2 Dec 2002.

Zimmer, Jessica. “What’s in a Name: Potrero Hill’s Parks and Schools.” The Potrero View. Jun 2017.