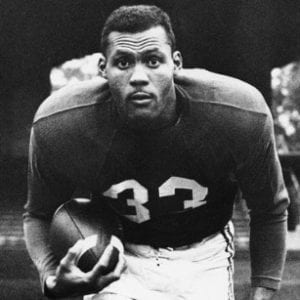

“Figures do not show his true value,” Ray Richards, Chicago Cardinals’ coach from 1955 to 1957, said of Ollie Matson. “When he is in the lineup, somehow the whole team is inspired.” In addition to motivating and inspiring his teammates, Matson also inspired people of rich, poor, white, and black families to follow their dreams and to fight for what is right.

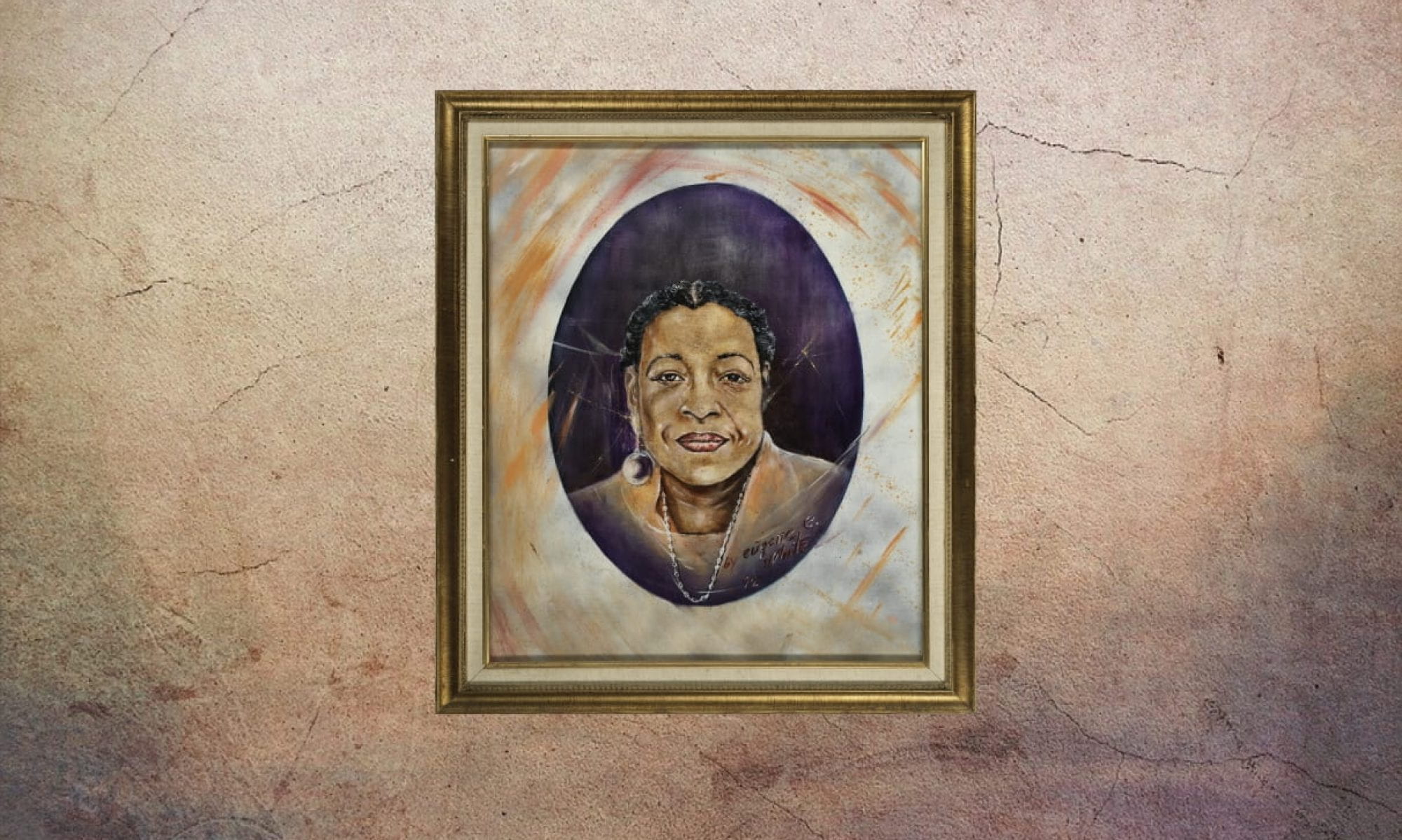

Ollie Genoa Matson II was born in Trinity, Texas, on May 1, 1930. He moved to San Francisco with his mother, Gertrude, when he was a teenager. In the city, Matson became known as an iconic All-American football player. While attending Washington High School, Matson displayed his impressive talent as a football player and track athlete. In 1947, San Francisco Chronicle reporter Don Selby said that “[Matson] gives every indication of being the hottest thing San Francisco high school football fans have seen in quite a spell.”

Matson’s performances also caught the attention of university scouts. He broke the world interscholastic 440-yard dash record with a time of 47.8 seconds; the old mark was 48.2 seconds. Standing 6 feet 2 inches and weighing 220 pounds, many people wondered how Matson had the ability to run so fast. When asked, he explained: “Speed and quickness, that’s what you need to return kicks. I was big, but I was swift for that size. I could either run past you, over you, or through you. I didn’t do a lot of hard cutting like Gale Sayers did. But we both had the peripheral vision to know where guys were going to be, and we had that speed to get there.”

Matson would later play for San Francisco City College, where he scored 19 touchdowns in one season. As a junior, he transferred to the University of San Francisco. He originally enrolled to play basketball, but was soon drawn back to the gridiron. Matson was a star of the legendary undefeated and untied 1951 University of San Francisco football team. He called this team “the greatest of all time” because of their dominant 9-0 record. Matson led the nation that year with 1,566 yards rushing and 21 touchdowns. The Dons were able to outscore opponents by an average of 31–8 because of Matson’s leadership. They beat College of the Pacific 47–14 in a game that was supposed to send the winner to the Orange Bowl. However, Coach Joe Kuharich was told that the invitation would be issued only if the team’s white players played. The team’s defensive star Gino Marchetti stated, “No, we ain’t going to go without Burl [Toler] and Ollie,” and in the end, the team decided to forfeit the Orange Bowl.

Although Ollie Matson was not able to play in the Orange Bowl, the next year he won a silver medal in the 1,500-meter relay and a bronze medal in the 400-meter race in the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki. Matson said that he cherished his Olympic medals the most because “In the Olympics you’re competing against the best there are. It isn’t the Iowa State Fair. It’s the world championship.” Once he was back from representing the United States, Matson was ready for an outstanding NFL rookie year. During his first season, Matson became the co-winner of rookie of the year honors in 1952.

Matson held the record for the most total yards gained in a season: 924 yards. He also held the record for most rushing yards in a game—163 yards. In his fourteen years of playing pro football, Matson had the ability to break down barriers to become one of the best. Throughout his career, he gained 12,844 yards on rushing, receptions, and returns.

Performances like these allowed Matson to be elected to six Pro Bowl teams and six All-Pro first or second teams. In 1972, Matson was elected to the NFL Pro Football Hall of Fame. He was inducted in the National Football Foundation’s College Hall of Fame in 1976. Matson retired in 1966 and began teaching physical education and coaching football at Los Angeles High School. He also coached running backs at San Diego State and scouted for the Philadelphia Eagles and was the special-events supervisor for 11 years at the Los Angeles Coliseum.

Matson had two daughters, Lisa Lewis and Barbara King, and two sons, Ollie III and Bruce. Family was important for Matson. He was proud of his medals, but he was most proud of his 50-plus years of marriage to his wife Mary L. Paige. He said, “It’s all about marriage. That’s the key right there. That’s what makes everything else feel so nice.”

Art Thompson, Matson’s nephew, released a statement from the family explaining that Matson suffered from a dementia-related condition late in his life. Before doctors were able to treat him, Matson died in his home in Los Angeles at the age of 80 in 2011. He had a full and exciting life. His desire to do what is right and his ability to do it with grace was awe-inspiring. He was and still is one of the best football players who ever played the game.

— Betsy Jacobo and Grace Jackson

Works Cited

Crumpacker, John. “Ollie Matson, NFL Hall of Famer of S.F., dies.” SFGate. 20 Feb 2011.

Harris, Beth. “Pro Football Hall of Famer Matson Dies at 80.” The Washington Times. 19 Feb 2011.

Kupper, Mike. “Ollie Matson dies at 80.” LA Times. 20 Feb 2011.

Litsky, Frank. “Ollie Matson, an All-Purpose Football Star, Is Dead at 81.” New York Times. 20 Feb 2011.

“Ollie Matson.” NFL Pro Football Hall of Fame.