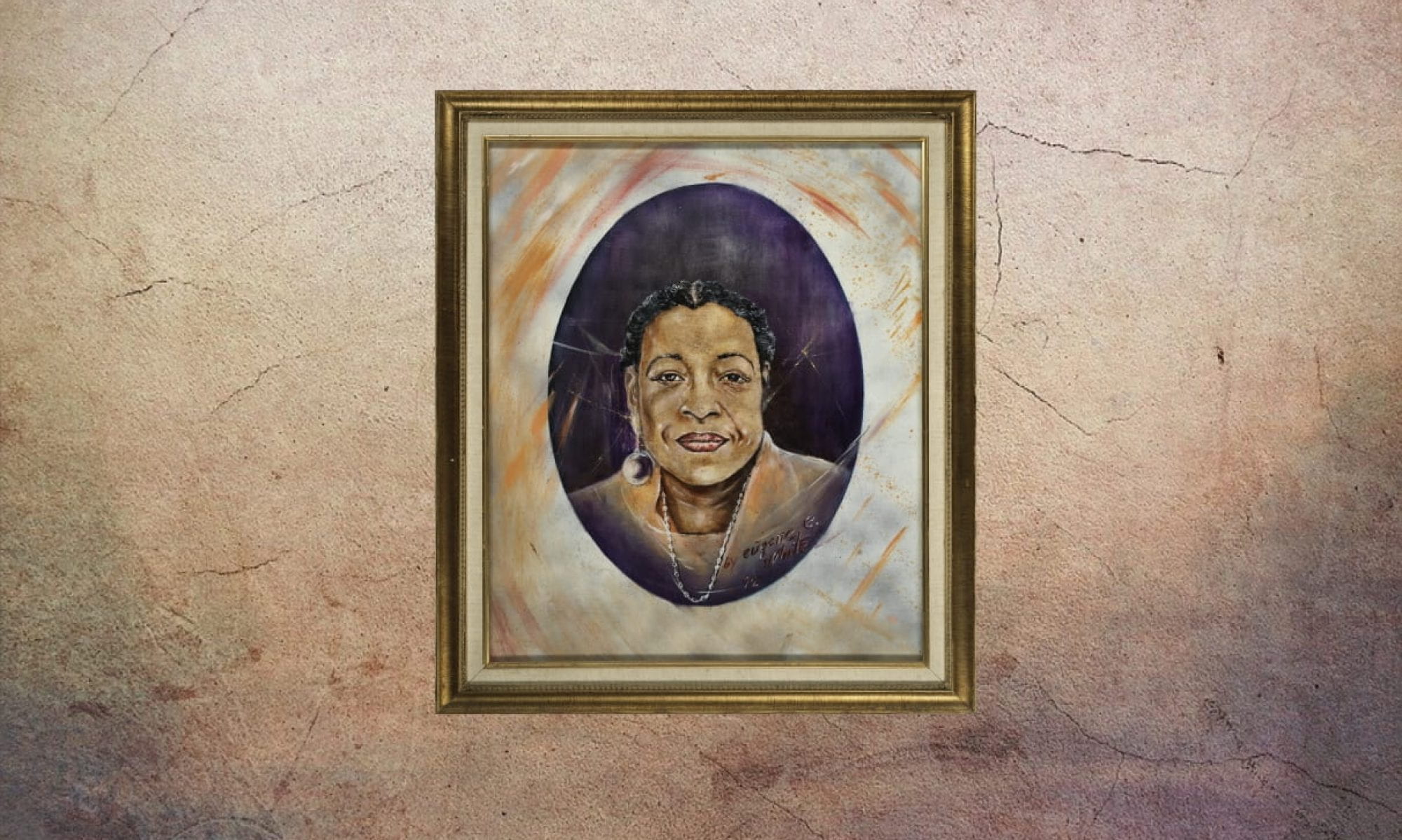

Mattie Jackson was born on October 3, 1921, in Blanchard, Texas. She grew up during the Great Depression and was the second youngest of seven siblings. Encouraged by her father to continue her education, she worked to develop important leadership and organization skills at Johnson’s Business College. After moving to San Francisco, she opened several small businesses and became an advocate for workers’ rights.

During the Great Depression, very few families were able to send children to school, and it was nearly unheard of to attend college. However, Jackson and all of her siblings received higher education. She graduated from Phyllis Wheatley High School, described by the Houston Chronicle to be “the finest Negro high school in the South.” Her next step in education was going to Johnson’s Business College. In an interview with UC Berkeley’s Regional Oral History Office, Jackson explained that she had “always wanted to be in business.” Her goal didn’t change when she followed her husband, John P. Jackson to San Francisco in search of jobs.

In 1945, she arrived in the city a few months after John had found work. She continued earning her business degree at Heald Business College in 1950, after which she opened her first business, Groove Records on O’Farrell Street. The culture in San Francisco was much different from what Jackson had experienced in Texas. In comparison, it was easy to find work as a black woman: “In Texas, I never would have applied, and if I had, I wouldn’t have gotten the job. This fair kind of treatment is one of the reasons I’m sold on San Francisco” (Miller). Jackson later became the owner of the Portrero Coffee Shop and opened a bigger record store on Post Street.

Although Jackson never decided to pursue advocacy, her leadership, organizational skills, and character naturally made her a good fit and drew her to the part. She participated in her first organized protest in 1947 after she accepted a job at the big name textile factory, Koret of California. She’d been hired as a “blind stitch,” one who does maintenance work on broken sewing machines. Although she had worked with Ben Davis, another textile corporation, her boss commented that she didn’t have what it took. He said that she wasn’t “going to stay here long.” In response to this comment, she conducted her own research as to why the factory production seemed to be lagging. She discovered that many Koret employees were being underpaid, yet management had denied any responsibility. The factory had already been unionized, but Jackson and other underpaid Koret workers decided that the best way to mobilize would be to organize their own strike. After back-and-forth negotiations, the management eventually agreed to pay for the missing wages. The strike lead to a grand victory.

In 1974, Jackson caught the attention of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) and joined the Pacific Northwest District Council (PNDC) which was a part of the ILGWU. During her time there she worked closely with San Francisco Mayors Moscone, Feinstein, and Agnos. Jackson’s involvement in the political realm not only focused on the commercial side of her business, but on the fundamental ethics between workers and managers. Appointed Vice President of the Commission on the Status of Women, commissioner for the Human Rights Commission, and President of the Board of Permit Appeals, Jackson pressed for more fair treatment for all.

From textile worker to full-time advocate, Jackson had chosen a career that vastly changed her life. By January of 1976, Jackson was appointed to the Board of Permits and Appeals, serving under the three mayorships of Moscone, Feinstein, and Agnos. She continued to remain politically active, particularly in regards to protecting the interests of her union, and remained in touch with her fellow union members well after retirement. She returned to school and took classes related to her union work and economics at the University of San Francisco. Jackson received many awards from churches, politicians, and communities for her union activities. Her last business was a secondhand store, En Vogue Collectibles, on Hayes and Ashbury.

On February 7, 2009, Mattie Jackson passed away. She is survived by her daughter and grandchildren. From her humble beginnings in rural Texas, Jackson’s uncompromising and assertive personality led to her becoming one of the most remarkable labor activists and entrepreneurs in San Francisco. Due to her vocal dissatisfaction with unjust labor standards, it comes as no surprise that Jackson earned a place within the high ranks of city politics. San Francisco is honored to have such a strong and innovative woman as a part of its vibrant history.

— Daaniyal Mulyadi

Works Cited

“Mattie Jackson.” [Obituary.] SF Chronicle. 16 Feb 2009.

“Mattie Jackson “Labor Leader, Business Woman, Public Servant and Activist” conducted by Nancy Quam-Wickham 1996, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. 2013.