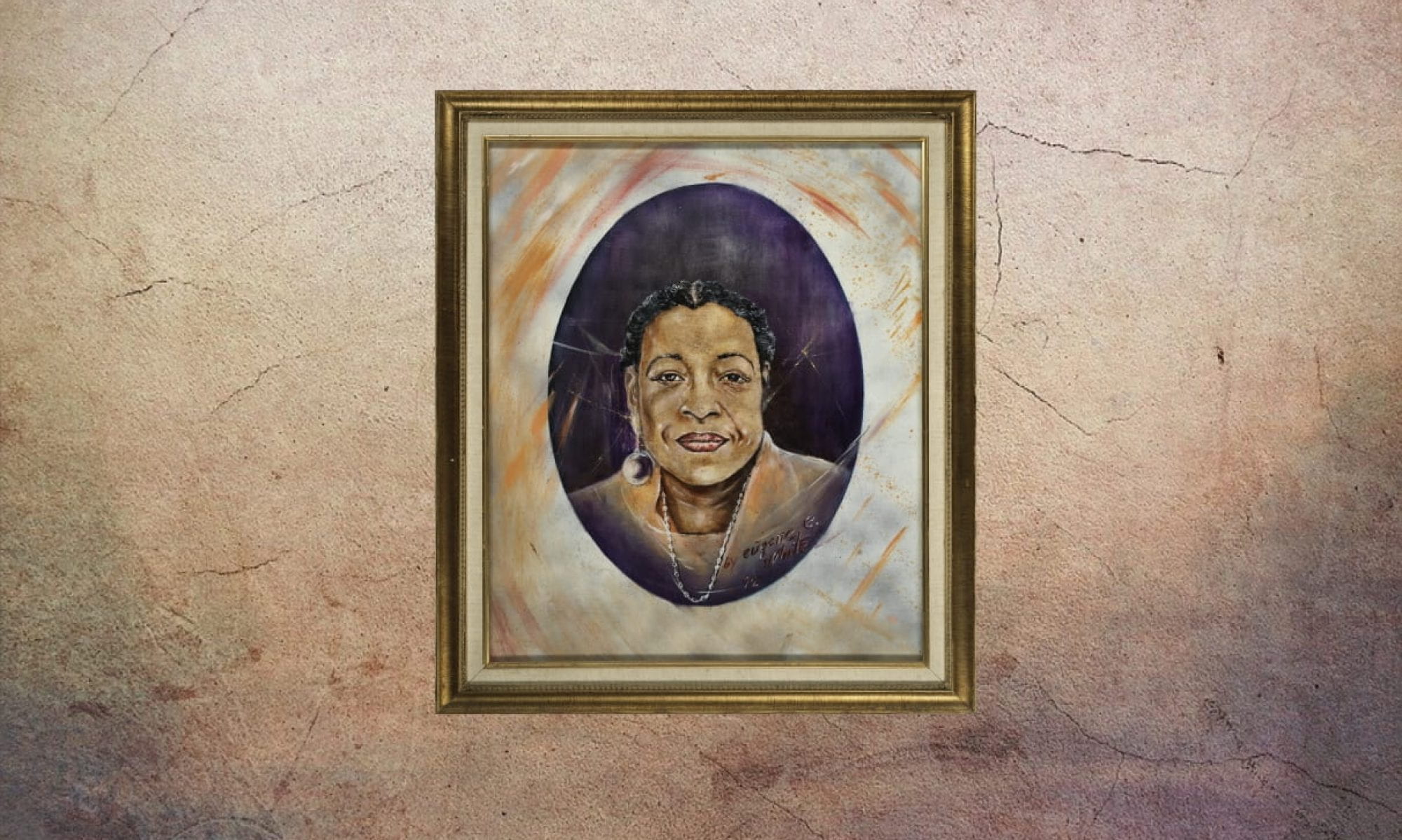

Sam Jordan exemplified diversity in his many accomplishments and his openness to others. Born and raised in Dallas, Texas, Jordan moved to San Francisco in 1948 to pursue his boxing career. His charismatic nature quickly sparked a following and a nickname “Singing Sam” because he would often sing to the crowd after he won a match. His drive and talent was easily noticeable, seeing as he won the Golden Gloves light heavyweight championship within his first year in San Francisco (Nevius). Unfortunately, his boxing career came to an early end when his vision started deteriorating due to cataracts (Tlumak). Though one career ended, Sam Jordan allocated his drive and passion to other areas. Including his work on the board of directors of the Hunters Point Co-Op, and specifically his interest in finding solutions to the large drug problem that occurred in Hunters Point (Tlumak). Being a part of the Hunters Point Co-Op was the impetus of his career as a community leader.

A few years later in 1959, Sam Jordan opened his historic bar and restaurant “Sam Jordan’s Tavern” (Bowcock). This bar and restaurant housed many famous singers such as, Big Mama Thornton and Sugar Pie DeSanto (Nevius). At the tavern, the community came together to sing, dance, eat and to simply have a good time. We can also see Sam Jordan had a big heart and genuine care for all of his community members (Nevius). Whenever someone couldn’t afford to pay for food, Jordan would set up a small table at the front of the bar and personally serve them himself (Nevius).

In 1963 at 38, Sam Jordan became the first black man to run for mayor of San Francisco. He ran as a statement against racial discrimination, to fight for better police protection, and to address San Francisco’s civil rights problems (SF Examiner). While campaigning he said, “All over America the Negro is waking up. There may be more bloodshed, and it could happen in San Francisco—but not if we have a Mayor who honestly believes that all people are equal and should have the same opportunities” (SF Examiner). His plan for San Francisco also involved improvement of education and housing progress (SF Examiner). Jordan was also planning on appointing people from all nationalities into government positions (SF Examiner). His plans and ideas mainly appealed to progressive ideologies that uplifted minority groups, and his campaign was revolutionary for his time. Unfortunately he lost the election and placed in fourth out of eight candidates. Even though Jordan lost he was still able to be a voice for minority communities and a voice for social justice. Jordan did not let his loss dull his continued drive and passion.

Sam Jordan’s restaurant was designated a historical landmark by Mayor Ed Lee in 2013.

It was later discovered, in 1976, that the FBI tried to sabotage Jordan’s mayoral campaign by trying to associate him with Socialist Workers Party, SWP (Irving). In 1978 there was an article written in the San Francisco Chronicle by Warren Hinckle that revealed the discovery of memos written for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) office in San Francisco leading to J. Edgar Hoover—the first director of the FBI—trying to find ways to derail Jordan’s campaign and image. Hoover’s idea was to write an anonymous letter to Jordan from a longshoreman that would “warn Jordan about the Commies in his midst in a way that would turn his campaign into a black-Trot battleground” (Hinckle). However, this idea proved ineffective because Jordan simply threw away the letter after it was found (Hinkle). Other things that happened during Jordan’s campaign, perhaps because of the FBI interference, was the harassment by the Alcoholic Beverage Control organization that claimed they were getting calls from black women stating that Jordan was serving alcohol to minors (Hinckle). Also, some of Jordan’s military friends told him that Sam Jordan’s Tavern was considered “off limits,” which was not true (Hinckle). Additionally, that same year in 1963 all of Jordan’s campaign records disappeared (Hinckle). When asked about why the FBI saw Jordan as a threat he stated, “I still can’t see where the FBI considered me any sort of political threat. If you ask me, doing all that to me was racist, pure and simple” (Hinkle). Though Jordan had the FBI against him, he was able to come in fourth place in the mayoral election, which is a huge accomplishment for a black man during a time of much discrimination.

Sadly in 2003 Sam Jordan passed away. His restaurant, however, has managed to stay open and is currently run by his son Sam, and in 2013 his restaurant was designated as a historical landmark by Mayor Ed Lee. Sam Jordan will forever be remembered as an influential man who gave back to his community. From his boxing days to his short political career, he was able to shed light on important social justice issues within San Francisco. His ability to keep moving forward and to fight for a more equal and just society for minorities will go down in history.

— Anthony Norman, Juliet Baires, Ashley Cruz, and Kendra Wharton

Works Cited

Bowcock, Robert H. Butchertown: A Collage of a San Francisco Institution during 1850–1969. Falcon Books. 2004.

Hinckle, Warren. “FBI’s ‘Dirty Tricks’ in SF.” SF Chronicle. 13 Jul 1978.

Nevius, C.W. “Sam Jordan’s Bar gets landmark status.” SFGate. 24 Jan 2013.

Tlumak, Joel. “Sam Jordan—the Man To Call at Hunters Point. ” SF Chronicle. 22 Feb 1972.