Born on March 28, 1931 in Eddy, Texas, former Superior Court Judge John Dearman became widely known for being humble in the court, once even advising a fellow judge to “keep one’s ego in check” and to never refer to oneself as “Judge” (Cahill). His history as a social worker helped shape him into a polite, patient, and respectful judge who would keep an open mind and listen to whomever took the stand, regardless of the alleged crime. Known as a kind-hearted and resilient individual, Dearman earned the respect of many throughout his career. He received a B.A. from Wiley College in Marshall, Texas, in May of 1954, and continued his schooling at Wayne State University Law School in pursuit of becoming a lawyer. While preparing for the bar exam after graduating from Wayne State, Dearman also worked as a social worker in Michigan. He began his career as a lawyer in 1959 when he left Detroit due to the fact that “no law firms in Detroit would hire a black attorney” (Egelko). After undergoing extreme prejudice in this community which he cared so much for, Dearman decided to move to San Francisco. It wasn’t long before he and Willie Brown started up Brown, Dearman & Smith, a law practice that continued for twelve years after its inception. This firm worked for years from the heart of the Fillmore.

While Dearman began settling into West Coast life, a war was brewing in the Western Addition. Homes were being torn down in the name of urban renewal and hundreds of people were being displaced as a result. This was a direct outcome of Justin Herman being appointed in 1959 as head of the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency (SFRA). Under Herman’s supervision, the SFRA A-1 Redevelopment Project began its work on turning the then two-lane Geary Street into the current four-lane Geary Boulevard. This project turned Geary into a “financial dividing line” between minorities and the wealthy, and landlords began refusing to rent or sell homes to African Americans (PBS). San Francisco’s racial prejudice had become so prominent that many living in the community began to take a stand in order to protect their homes. The NAACP and other organizations coordinated sit-ins. On one occasion, Willie Brown and John Dearman sat against developments in Forest Knolls, a protest that would catapult them into headlines of local newspapers and label them as public figures. The community’s civil disobedience was effective in many ways, and helped result in the Fair Housing Ordinance of 1968. This led to the creation of the Fair Housing Act of 1968. This act did not permit discrimination in the selling, renting, or financing of housing based on race, religion, national origin, and sex. This was a tremendous victory within the community and reflected Dearman’s love for his neighborhood and its well-being.

Before being appointed by Governor Jerry Brown to the San Francisco Municipal Court in 1977, Dearman cultivated a close friendship with Willie Brown. They connected over their struggles, their tenacity, and their love for the community. Brown and Dearman later decided to pursue a professional partnership because “the legislators [then part-time] were making only $500 a month, and Willie had three children” (Egelko). Dearman and Brown worked on many notable cases, representing athletes such as former Warriors players Nate Thurmond and Rick Barry (Brown). As the years moved forward, so did the pair’s friendship. Following Dearman and Brown’s partnership of twelve years, Dearman accepted his appointment to the Municipal Court Bench on March 28, 1977. A couple of years later, he moved up to the San Francisco Superior Court and began acting as Presiding Judge from 1990 to 1991. Dearman retired on March 28, 2009, as one of the longest-serving judges with 32 years of service on the San Francisco bench. He went on to participate in the Assigned Judge Program, an opportunity for “active or retired judges and justices to cover judicial vacancies” (Park-Li). Despite taking leave as a permanent presider on the bench, Dearman could not bring himself to leave his role in the courts entirely.

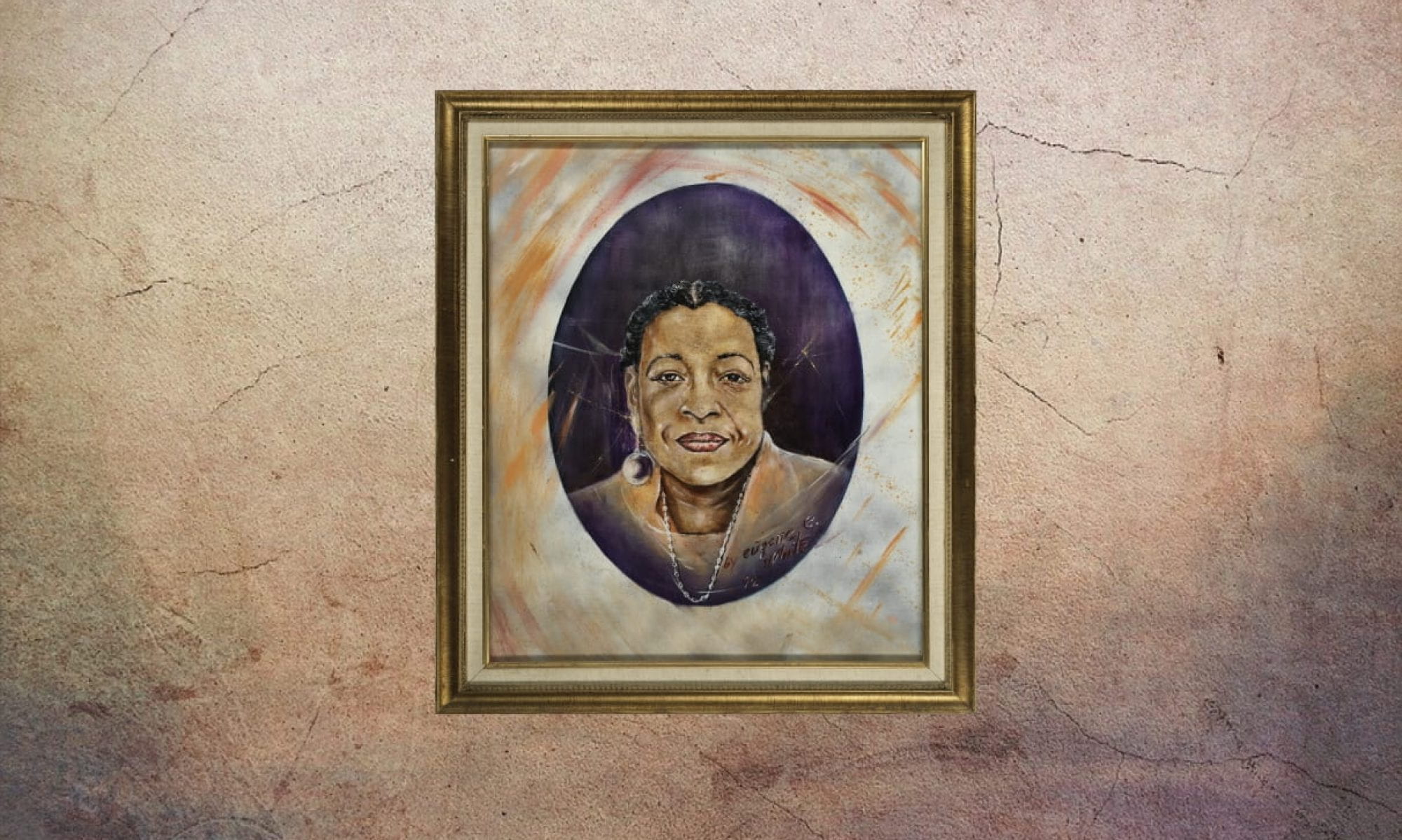

Dearman represented the heart of the Western Addition as someone who promoted social change in San Francisco during a tumultuous time. His involvement in local community organizations and his dedication to grassroots action cemented Dearman’s place in San Francisco history. Dearman embodied the determined, hardworking, and kind-hearted spirit of African American San Franciscans, diligently making progress even when facing numerous roadblocks along the way. He is known as an understanding judge, a local leader, and a kind face among the crowds. John Dearman’s portrait upon the Ella Hill Hutch Community Center mural is well deserved because he contributed so much to the San Francisco community.

— Anya Kishen and Rachael Sandoval

Works Cited

Brown, Willie. “Professional basketball deals then and now.” SF Chronicle. 31 May 2015, C1.

Cahill, William. “Reflections on Ten Years on the San Francisco Superior Court.” Bar Association of San Francisco. Aug/Sep 2000.

Egelko, Bob. “Three Questions For: Judge John Dearman.” SFGate. 12 Apr 2009.

Park-Li, Gordon. “Longest-Serving Judge on the San Francisco Bench Retires After 32 Years.” Superior Court of California. 6 Apr 2009.

“Fillmore Timeline 1860-2001.” PBS.

Smith, Pam. “SF’s Judge Dearman Retires, But Doesn’t Leave, Exactly.” Legal Pad 6. Apr 2009.

Wolf, Kathy, M. “California Courts and Judges.” James Publications. 2009.