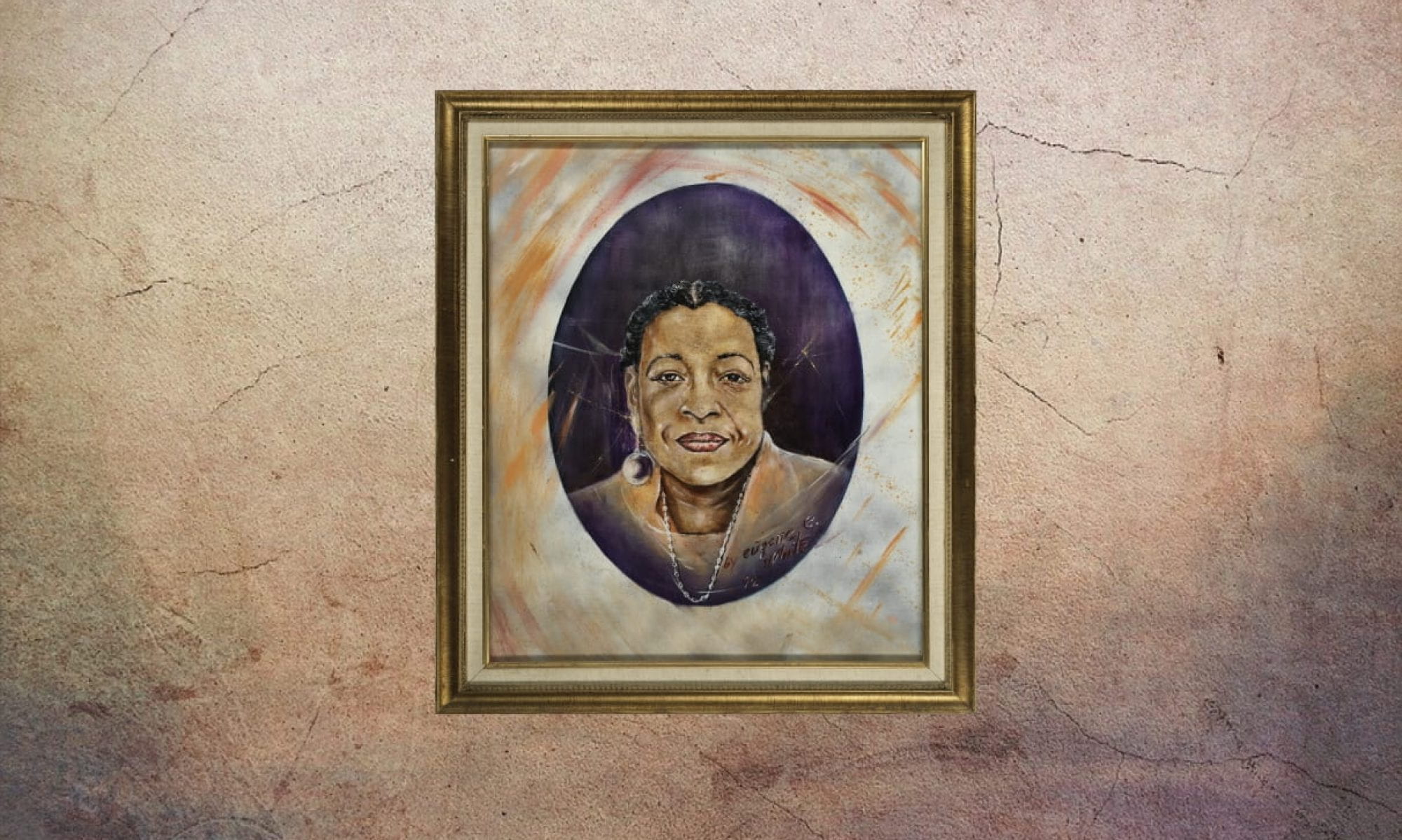

Education is a formidable force for reformation and change, and Ms. Jule Anderson, a board member of the San Francisco Unified School District from 1978–1982, represented that ideal. She fought to make San Francisco schools more inclusive and equitable. Her leadership and strength during an era of heightened racial tensions continues to serve as a model for educators today.

Jule Anderson brought a lifetime of civic activism to the SFUSD during a time of incredible change. Anderson was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi, at the height of Jim Crow. As a young woman she ventured west, enrolling in and graduating from San Francisco State University with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Economics. She later received her Master of Public Administration degree from Golden Gate University. Before her appointment to the SFUSD, she worked as the Director of Special Programs for Disabled Students and Women at the Contra Costa Community College in San Pablo. Her passion for special education programs emerged, in part, because she had a special needs child with her husband.

Anderson was involved with San Francisco educational politics during an era of increased tumult. During the 1950s and 1960s, schools in the United States had been a hotbed for racial tension. The 1970s were an era of continued racial struggle and the SFUSD was the subject of two important legal decisions. First, in the 1971 case Johnson v. San Francisco Unified School District, the Ninth District Federal Circuit Court found that school district officials were still using school attendance boundary lines to segregate not only black students but those of Chinese ancestry and other minorities as well. The practice was already found to be discriminatory and unconstitutional in 1954 in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case. The Court decreed that the school district was required to institute a busing system to address racial disparities within the city.

Second, in the 1974 case Lau v. Nichols, the United States Supreme Court approved the issue of a consent decree against San Francisco Unified School District. The court found SFUSD wasn’t offering adequate supplemental language instruction to students with limited English proficiency, which was a legal violation of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The consent decree mandated the creation of English language learning programs along with bilingual courses for public school students.

San Francisco Unified School District had still been procedurally obligated to fulfill both the 1971 busing decree and the 1974 bilingual language consent decree during Anderson’s appointment to the board by Mayor George Moscone in 1978. She sat on the community relations and integration committee, the curriculum and instructional support committee, and the personnel and evaluation committee. The first two committees were tasked with creating the framework for legal compliance. As a result, SFUSD published the Educational Redesign and Implementation Plan later that year.

Mrs. Anderson would reaffirm her commitment to ensuring positive learning outcomes to black students. She sponsored a resolution for student athletes to maintain a C grade average in order to participate in athletics. When she was interviewed by Dan Borush for The Progress newspaper, she cited “exploitation in permitting youngsters to spend an excessive amount of time in practice or playing a varsity sport and little time doing anything academically” as the reason for her support.

Jule Anderson’s activist approach towards special needs programs was key to addressing the changes SFUSD needed to implement. The Educational Redesign and Implementation Plan identified three significant shifts in school policy. First, a policy of integration, mandating “each regular school shall have no more than 45 percent of a single racial or ethnic group in pupil population.” The school district would pay for the busing of students into new schools to meet the integration requirements, particularly within the Bayview, along with new courses designed for integrating bilingual speaking students into school curriculum. Programs were also created to cater to the unique challenges of special needs students. Anderson lent her experience and expertise to the redesign, with particular sensitivity towards special-needs students.

Anderson dutifully served the SFUSD until 1981, when she decided not to run for reelection. Instead, Anderson went on to sit on the Board of the California Alliance of Black School Educators, Aid to Retarded Children (as it was then known), and the San Francisco African American Historical and Cultural Society. Although Jule Anderson has left San Francisco for Atlanta, where she now resides, she left a positive legacy for students of the SFUSD and indeed for all citizens of San Francisco.

— Chiweta Uzoka, Jesse Cortes, Meghan Grant, Zoe Foster, and Marcelo Swofford

Works Cited

Borush, Dan. “Interview with Jule Anderson.” The Progress. 1978.

Johnson v. San Francisco Unified School District. 500 F. 2d 349. United States Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit. 21 Jun 1974.

Lau v. Nichols. 414 U.S. 563. Supreme Court of the United States. 21 Jan 1974.

McCormick, Erin. “Census shows black population plummeting in last decade in S.F.” SF Chronicle. 17 Jun 2001.