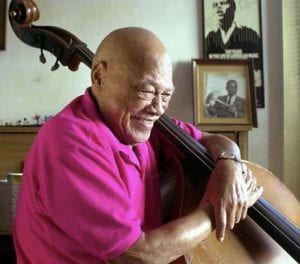

The city of San Francisco, when compared to places like New York or Los Angeles, offered limited musical opportunities for African American big-band bassists during the 1950s. However, Vernon Alley wouldn’t have wanted to play anywhere else. “Where else is there?” Alley asserted. Although he was born in Winnemucca, Nevada, on May 26, 1915, Alley felt like San Francisco was his home, expressing, “All I remember is San Francisco. I’ve lived here all my life.”

Vernon Alley and his brother Eddie, a distinguished drummer in the San Francisco music scene, came from humble beginnings, both bussing tables at Topsy’s Roost. Alley soon became a star high school football player. In his senior year, he was recruited by numerous prestigious colleges and universities, but chose instead to attend Sacramento Junior College, spending his time there as a music major playing the clarinet, double bass, and football. After training at Camp Robert Smalls, Alley enlisted in the Navy in 1942 and was assigned as a musician to St. Mary’s Preflight School during World War II.

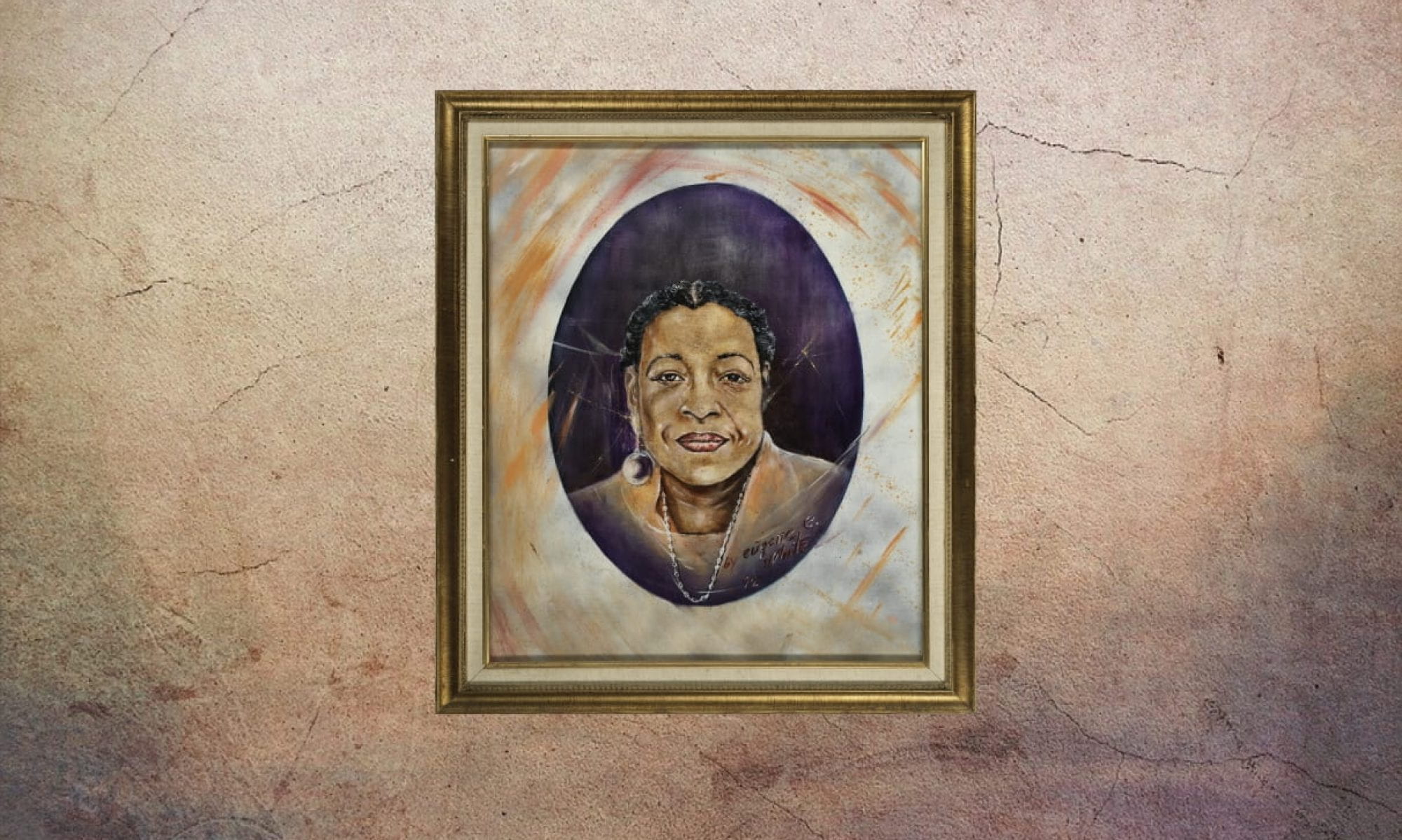

Upon his discharge Alley found an opportunity to pursue his passion for playing bass by joining Wes Peoples’ Band. The band had been known to fight color standards in the city by playing in areas where black people were not welcomed at the time. Early in his career, Alley played with Saunders King, the Lionel Hampton band, and Count Basie, to name a few. During his time with the Lionel Hampton band in 1940, Alley explored the electric bass, an extraordinary sound not yet familiar to many. Having come from a musical family, it was only natural for him to start a band of his own, The Alley Trio was composed of Jerome “Jerry” Richardson, who played clarinet, alto saxophone, and flute, Bob Skinner, who played piano, and Alley on bass. As his career advanced, Alley performed with well-known vocalists like Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday. He also played with and was inspired by other stars such as Duke Ellington, Erroll Garner, Nat King Cole, Dizzy Gillespie, and Charlie Parker. A star in his own right, Vernon Alley had his own show, “Down Vernon’s Alley,” and also appeared on “Nipper’s Song Shop” and The Merv Griffin Show. He was also the musical director of the Blackhawk jazz club. Alley appeared in “Reveille with Beverly” in 1943 alongside other great musicians of the time. In the latter part of his career, he joined the Musicians Local 6 union as a board member and became one of the first black members of the Bohemian Club, which was reserved for influential journalists, artists, musicians, and politicians.

In 1993, Vernon Alley was voted into the San Francisco Prep Hall of Fame. In 2002, he received the presidential medal from San Francisco State University, where he graduated in 1940 and continued to perform at alumni events. Vernon continued to be a devout public servant, joining the San Francisco Arts Commission. The city of San Francisco commemorated his influence by naming an alley between two buildings on Brannan Street “Vernon Alley.” Alley’s musical prowess was acknowledged by the Human Rights Commission, who recruited him not only to be a member, but to also serve as Musical Director for “Evolution of Blues.” As a member of the Human Rights Commission, Alley passionately fought for civil liberties and advocated against police discrimination.

Despite being an icon of success, Alley had to fight discrimination all his life. In an interview with Blake Green, Alley remarked, “People think that since I’m from San Francisco and a musician, I didn’t see any discrimination.” Nevertheless, Alley succeeded in spite of the racism and discrimination that he faced. His musical finesse is attributed to his persistence and determination, traits that cannot be undermined by his pure talent alone. Alley’s musical legacy is that of an inventor and revolutionary. He pioneered the melodious, rather than rhythmic style of bass playing and he brought what’s often considered a background instrument front and center. Vernon Alley’s music exemplifies his journey, a background man who earned his own spot at the forefront of the music industry.

The San Francisco Jazz Festival honored his success by creating a well-attended tribute called “The Legacy of Vernon Alley.” Indeed, Alley’s dedication to San Francisco as a musician and activist exemplifies what a changemaker is. Alley combated racism with persistence and commitment to art as a prevailing vehicle for change. Beyond his love for the city of San Francisco, his love for the people of San Francisco always triumphed. Alley recalled, “Oh, if I had really wanted to be a big man, I guess I would have gone to New York or Los Angeles. But I was never inspired to do that. I’ve always liked to be able to go down the street and say hello to people.”

— Kimberly McAllister, Zoe Foster, and Jesse Cortes

Works Cited

Chadbourne, Eugene. “Vernon Alley.” AllMusic. 2017.

De Roos, Bob. “Biography for Breakfast.” SF Chronicle. 25 Jul 1950.

Green, Blake, “That Swinging Alley Cat,” SF Chronicle. 9 Jun 1976.

“‘I Am American Day’ Features Jazz Group,” SF Chronicle. 9 Sep 1955.

“Jazz Legend Vernon Alley to Receive Presidential Medal.” SFSU. 6 May 2002.

Pepin, Elizabeth and Lewis Watts. Harlem of the West. Selvin, Joel, and Peter Fimrite. “Vernon Alley, 1915–2004.” SFGate. 5 Oct 2004.

Vacher, Peter. “Obituary: Vernon Alley.” The Guardian. 17 Nov 2004.