“I was always told when I was growing up that I had choices—even when I really didn’t have a whole lot of them at the time—it was what I [would do] that would make a difference in my life.” Born on May 23, 1926, in Brooklyn, New York, Aileen Clarke Hernandez was raised in a family that inspired and encouraged change. Both of her parents immigrated from Jamaica and became American citizens. Her father, Charles Clarke, worked in the art supply business, and her mother, Ethel Clarke, was a costume maker and seamstress for the New York Theater District. Growing up, Hernandez and her brothers learned how to both cook and sew “because her parents believed that no gender distinction should be made.” Her parents stood for equality—whether it be race, gender, or class. All of this impacted and shaped her education.

In 1943, as a valedictorian and emerging scholar, Hernandez attended Howard University in Washington, D.C. There she served as editor and writer for the campus paper, The Hilltop, and even wrote a column for the Washington Tribune. In 1946, she joined the Kappa Mu Honor Society. A year later, Hernandez graduated from Howard, magna cum laude, with a bachelor’s degree in political science and sociology (League of Women Voters of San Francisco). Both of these degrees would aid her in her future endeavors with community. In 1959, she received a master’s degree in government from Los Angeles State College, summa cum laude (League of Women Voters). Hernandez also studied at New York University and the University of Southern California. She also received an honorary doctorate in humane letters from Southern Vermont College in 1979 (League of Women Voters). Hernandez’s first involvement with social movements started in 1951, when she joined the West Coast division of the International Ladies Garment Worker Union in California.

Standing alongside renowned feminist Betty Friedan, Hernandez and others came together to form the National Organization for Women (NOW). As a co-founder, Hernandez and the members worked on behalf of women in the workplace (Napikoski, Thought Co). In 1970, Hernandez succeeded Friedan and became the second president of NOW (Makers). Five decades after the 19th amendment was passed, NOW took action to show the presence and power of second-wave feminism with the Strike for Equality March (Cohen). This movement boosted NOW’s base by 50% (Cohen) and was described as “easily the largest women’s rights rally since the suffrage protests” (Cohen). Some accomplishments that were gained after the march include pushing for gender equality in work spaces and in education through the passing of Title IX in 1972, the legalization of abortion in all fifty states in 1973 with the Roe v. Wade case, and the advancement of childcare through the passing of the Comprehensive Child Development Act in 1971 (Cohen).

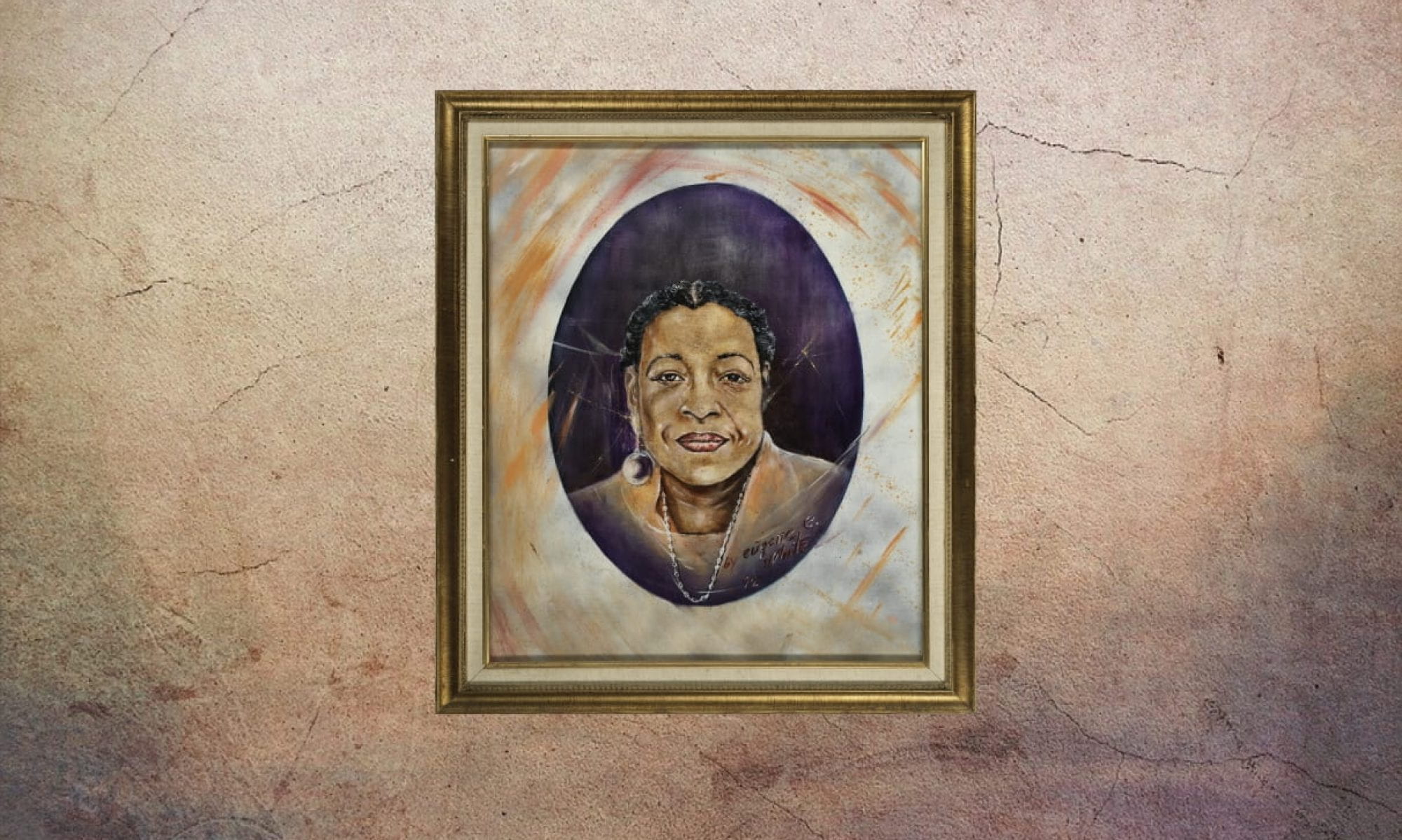

Aileen Clarke Hernandez was co-founder and president of NOW (National Organization for Women)

In addition to her work in NOW, Hernandez enforced the Anti-Discrimination Law in 1959. Three years later, she became the assistant chief of the California Division of Fair Employment Practices. Because of her dedication, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Hernandez as the Commissioner for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) (Makers). She was the first woman commissioner and second person of color to hold the position (Makers). With her role, she focused on Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which “outlawed discrimination based on sex, race, color, national origin, and religion”(Gould). Disappointed with the EEOC’s inability to enforce this law, Hernandez resigned as commissioner. During an interview with KQED, she shared: “We did not have power to make any changes in those days.”

Nevertheless, her work continued. Her passion in intersectional feminism led her to co-found the group Black Women Stirring the Waters in 1984 (Makers). The group consisted of black women who engaged in discussion about their own views and personal stories of dealing with and overcoming difficult situations in their lives (Makers). Their stories eventually were published and can be bought online or found in the Oakland Public Library. She is currently one of the chairs of California Women’s Agenda (CAWA) (Makers). In 2005, she “was one of 1,000 women from 150 nations who were collectively nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize” (Napikoski). Her contributions have relieved many communities in San Francisco that face similar intersectional dilemmas. She is more than outspoken about these issues and encourages outreach to all corners of a community. Her dedication to education and her humble upbringing helped to catapult her to where she is now. Her generous efforts through charity and activism continue to inspire many.

— Jazlynn Pastor, Alice Alvarez, and Olivia Walker

Works Cited

“A Different Kind of Reproductive Rights.” Makers. “Aileen Clark Hernandez.” Civic Makers, The History Makers. 8 Nov 2013.

“Aileen Hernandez.” Veteran Feminists of America, VFA. 2018.

Cohen, Sascha. “Women’s Equality Day: The History of When Women Went on Strike.” Time. 11 Mar 2013.

Gould, Suzanne. “The Untold Story behind the Civil Rights Act.” Empowering Women Since 1881. AAUW. 30 Jun 2014.

“International Ladies Garment Workers Union (1900-1995).” International Ladies Garment Workers Union (1900-1995), The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project.

“LWVSF Centennial Celebration Honorees.” League of Women Voters of San Francisco. Feb 2011.

Napikoski, Linda. “Aileen Hernandez — Feminist Civil Rights Activist.” ThoughtCo, About. 1 Apr 2017.

Teipe, Emily. “Aileen Clarke Hernandez.” Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, Research Starters. 2015.