Willie Hector was a phenomenal football player, but more importantly he was a role model. He and his wife, Ollie Hector, would serve as pillars of the Western Addition community and represented strength and commitment within the neighborhood. Willie was born in New Iberia, Louisiana on December 23, 1939, but later immigrated with his parents to Mill Valley in Northern California. His prolific athletic abilities were noticed at an early age. He enrolled in Tamalpais High School were he became a standout football player and track and field athlete. Willie was recruited to play at the University of Pacific in Stockton where he played football and ran in track and field. His talent shined at the University of Pacific, specifically as a football player. The Los Angeles Rams drafted him in 1961 as a guard. His superior athletic ability helped him excel in the highest levels of the game, even though he was significantly undersized. In Proverb G. Jacobs book Autobiography of an Unknown Football Player, he described Willie as “an undersized guard on the Rams team who couldn’t block me” (p. 333). He played several seasons for the Rams, Broncos, and the Calgary Stampede in Canada.

Although he took his professional career seriously, Willie always imagined a life after football. During the off season, he would attend university classes. While he was playing, he earned a master’s degree in physical education. After his professional football career ended, Willie decided to become a football coach. He started his coaching career at Tamalpais High School in 1966. He coached at the high school level for two years, where he set state and national records. He then decided to move into the city, becoming an assistant coach for the City College of San Francisco’s football and track and field teams. After eight years of assistant coaching, Willie got the opportunity to replace CCSF head football coach Arthur Elston. He was interviewed along with assistant coach George Rush. An article published in The Sun-Reporter detailed the inside story of City College’s football coach hiring competition.

In a voting process to elect the next football coach, there was a voting board that consisted of past head coach Arthur Elston, two of his loyal assistant coaches, the CCSF athletic director, and the president of the college, Dr. Washington. The votes were allegedly kept secret, however, somehow they were leaked to the public. The voting board had decided to award the position to George Rush, former player under coach Arthur Elston. The Sun-Reporter claimed the board’s hiring decision was racially motivated and wasn’t reflective of the actual merits needed to be a successful football coach. However, President Washington decided to nullify the results of the voting board and appointed Willie as the head football coach.

The decision caused an immediate uproar. Washington decided to publicize the decision by sending his athletic director to San Francisco newspapers. However, the athletic director decided to publicly ask President Washington to reconsider his decision. The hiring debacle heightened racial tensions within the university and in the city. Finally, after much deliberation, CCSF chose to default to their original decision, George Rush.

Although the decision caused great upheaval, it didn’t affect Willie’s resolve. His enthusiasm for athletics translated into a team-player mindset in his academic career. He dedicated himself to mentoring young athletes and guiding them to both athletic and academic success. In a 1977 Sun-Reporter article, Willie said: “The first year out of high school is tough on a youngster, especially if the athlete is from the ghetto and doesn’t have the background to study at the level of the other students who have been preparing for college for years” (Ness). Willie put it upon himself to mentor athletes as if they were his students. He was an influential voice within the Western Addition because he was an all-star student, talented football player, and a devoted community member. His personal experiences generated his ability to be both humble and informative. Willie’s concern regarding the success of students’ careers foreshadowed his shining attitude as a parent.

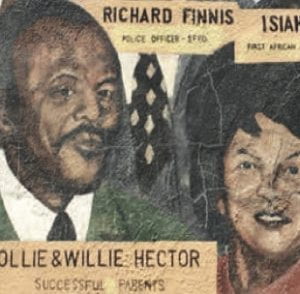

Willie used his positive disposition to raise three outstanding boys along with his wife, Ollie. In an SFGate article, “Faces of Black Success,” Carol Ness points out the significance of Willie and Ollie’s productive parenting style. Famed Western Addition community leader Lefty Gordon explained the significance of the Hectors and their contribution to the neighborhood by stating, “Oftentimes here, African Americans, come from dysfunctional families. The Hectors instilled in their three sons a hell of a work ethic. They all went to college and found a skill. They all built their own homes.” One son, Robert Hector, went on to create an inclusive support system for the youth in the Western Addition. He was one of the first employees at the Ella Hill Hutch Community Center in San Francisco, where he worked for nearly three decades. His longevity and commitment at the center is a reflection of his parents’ extensive support and love.

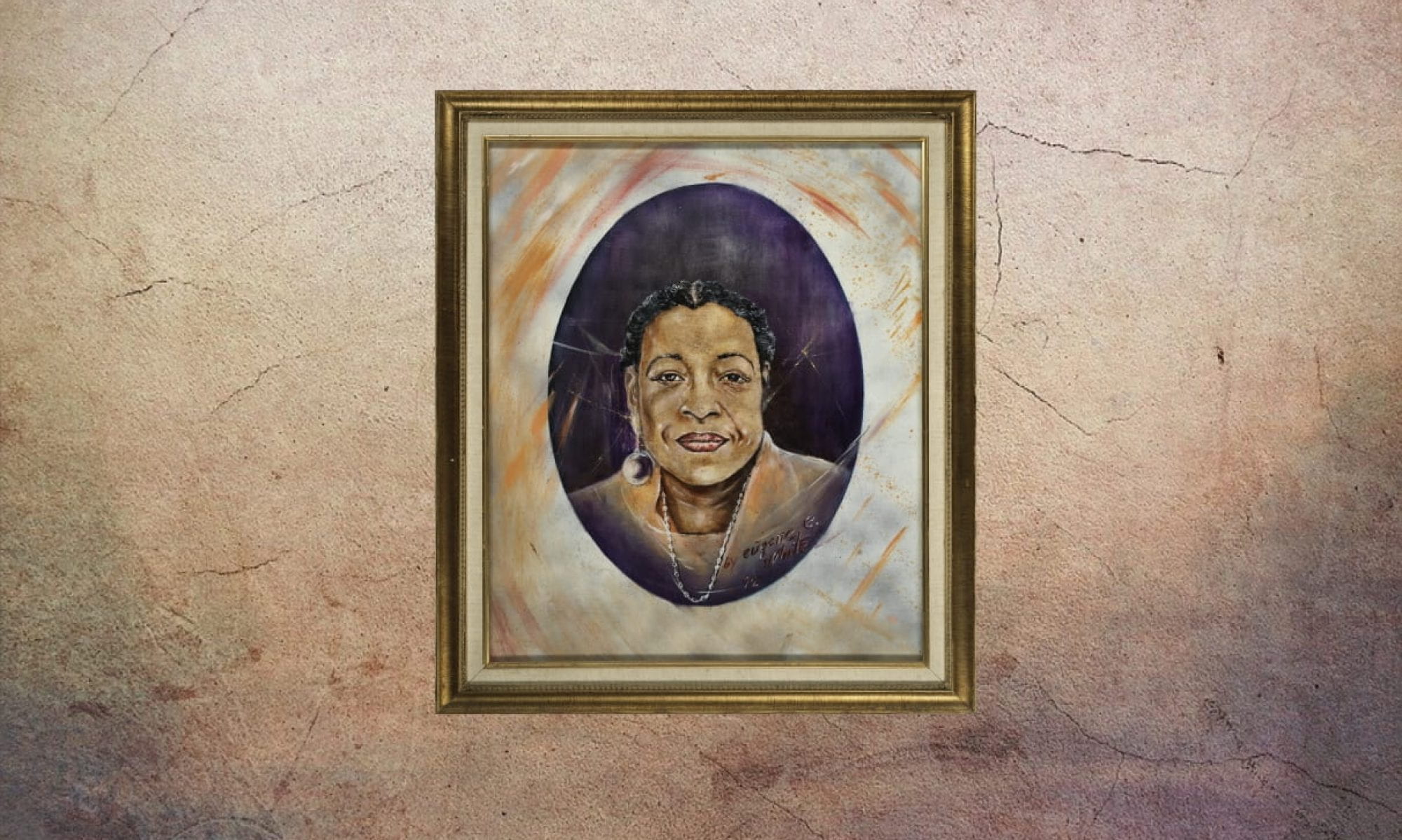

The example that the Hectors have set has been important for generations of Western Addition children and families. Their example awarded them honorary status on the murals of the Ella Hill Hutch Community Center.

— Matt Chiodo and Olivia Walker

Works Cited Ness, Carol. “Faces of Black Success.” SFGate. 1999.

“Pacific Athletic Hall of Fame.” 2018.

“Regional Directors.” AMBLP.

“SF Human Rights Commission.” SFGov. 2018.